Only in the make-believe world of analytical models can negative nominal interest rates be argued to do any real good.

Last October, Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, ordered UK commercial banks to demonstrate their preparedness for the possible introduction of a negative interest rate policy (NIRP). From one perspective, this is merely a prudent step that enhances the central bank’s policy toolkit. From another, it is a further unwarranted and ill-advised step towards the complete abandonment of monetary control. The NIRP conversation sits alongside November’s £150bn extension of the Bank’s asset purchase facility, which will propel the annual growth rate of the money supply, currently 12%, to around 17% by March 2021. It would be remarkable if this development did not excite the inflation expectations of the UK public.

After more than a decade of very low interest rates in many advanced economies, we have become inured to cheap money and seduced by central bank propaganda that structural forces – debt, demographics and inequalities of income distribution – are primarily responsible for this unusual state of affairs. Never underestimate the capacity of policy-makers to draw the wrong conclusions about economic behaviour. Rather than consider the possibility that the policy of persistently low interest rates might itself be responsible for disappointing economic performance, they are magnetically attracted to the notion that the current policy would be successful if only interest rates could be lowered even further, into negative territory. Negative interest rate policy is an extension of a flawed argument, reductio ad absurdum. The beatings will continue until morale improves!

Negative interest rate policy is an extension of a flawed argument, reductio ad absurdum. The beatings will continue until morale improves!

Much of the blame for this psychosis can be traced to the elegant analytical models in common use among academics and central bank research departments. The most widely used of these models is labelled New Keynesian and consists of three key equations that describe macro-economic behaviour. These are: versions of the Phillips curve, a representation of the relationship between economic slack and inflation; a Euler equation, which connects the consumption decision and the interest rate; and a monetary policy (Taylor) rule, which sets the optimal path for interest rates for given departures of inflation and unemployment from target. Numerous conditions are imposed on the model, for example that policy-makers set policy in a time-consistent manner and that central banks change interest rates only gradually.

Only in the make-believe world of analytical models can it be argued that negative nominal interest rates have beneficial long-term economic effects. Advocates of NIRP argue that, even though the classical interest rate channel is weaker, there is a more than offsetting positive signalling effect, whereby expectations regarding short-term money market interest rates and long-term government bond yields are reduced, inflation and GDP growth expectations are raised and aggregate demand is boosted by the lowering of real interest rates. Such models generally fail to take account of moral hazard behaviours, balance sheet effects or the impacts on financial stability. These are the same models that assumed away debt delinquency and so failed to anticipate the economic and financial traumas of 2008-09.

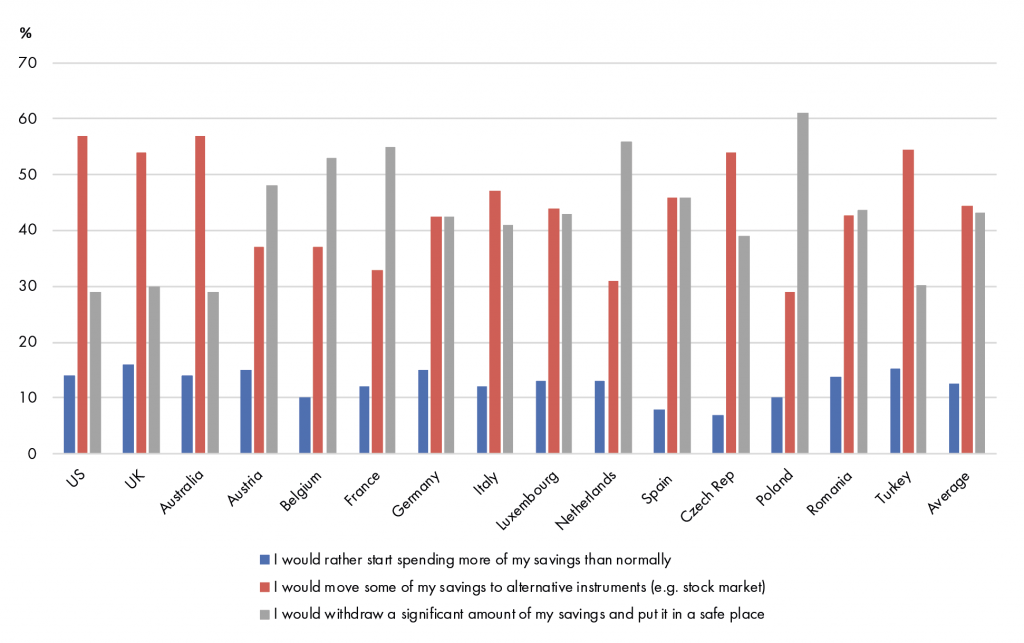

At best, NIRP is a gimmick that has favourable short-term announcement effects, such as gains in asset prices that strengthen bank balance sheets. The experience of countries that have persevered with NIRP is that the trouble it causes accumulates over time. Notably, the Swedish Riksbank abandoned negative rates at the end of 2019 in the face of mounting evidence of adverse side-effects. Examples of the unintended adverse consequences of NIRP are the erosion of the returns to long-term savings institutions; the sustenance of zombie companies that would collapse without cheap money; the incitement to reckless borrowing; perverse effects on household saving rates and an increase in the hoarding of physical cash (see chart); and the erosion of eurozone bank profitability through negative rates paid to the European Central Bank in the context of Target2. Banks that cannot earn an adequate net interest margin from domestic credit intermediation are likely to be driven to risky lending activity in foreign parts.

Breakdown of respondents moving money out of savings accounts if there were a negative interest rate on savings accounts

A comprehensive critique of NIRP would require many more words than this article affords. My objections are summarised under four headings. First, while policy is made in nominal terms, it is real interest rates that matter most. Negative real interest rates do not require negative nominal rates. Once the inflation genie is out of the bottle, the debate about negative nominal rates will be obsolete. Second, negative nominal rates, even more than zero rates, signal the desperation of policy-makers and engender fearful, precautionary and radical responses in the general population. Third, negative nominal rates are more likely to induce commercial banks to chase higher returns from risky lending and imperil financial stability. Finally, negative nominal rates play havoc with business models and undermine the solvency of the pension fund and life insurance industries at a time when these institutions are already challenged by adverse demographic trends.

Given these powerful objections, it is reasonable to speculate that the Bank has an ulterior motive in entertaining the possibility of the use of negative interest rates at this juncture: namely to seek to weaken sterling ahead of the inevitable buffeting of the UK economy as it confronts the simultaneous impacts of covid-19 and exit from the EU on trade terms worse than those obtained by Canada.

Since the global financial crisis, the Bank of England has repeatedly postponed the decision to commence the normalisation of interest rates. After the Brexit referendum vote in 2016, it lowered them in a bizarre act of pre-emption. After two reluctant 25 basis point increases in 2017 and 2018, Bank rate was quickly dropped to a mere 0.1% when the virus struck. The Bank has sought to wrap our economy in the cotton wool of low interest rates, in the belief that the inflationary wolf was tethered. Worse, the perpetuation of near-zero interest rates has emboldened the socialist argument that asserts it is the moral duty of savers, and savings institutions, to accept low or zero returns in pursuit of the higher purpose of building tomorrow’s infrastructure and protecting the environment. The coronavirus has laid bare the bankruptcy of the UK’s monetary policy framework: the wolf is free to roam.