This article was first published in March 2018.

After a break of a year, it is always a shocking experience to stand at the top of the Cresta run again, preparing to hurl myself head first down an ice chute at over seventy miles an hour. Existential questions that my mind asks like ‘why are you doing this?’ receive answers like ‘because it is fun’ but just don’t seem convincing at all. Ensuring that one does not come a cropper on the infamous corners of Thoma, Shuttlecock or even the dangerous finish banks certainly focuses the mind.

I am not convinced that riding the Cresta is an architectural experience but it is definitely a sensory one. At minus 15 degrees Celsius the ice glimmers enticingly in the morning sun but don’t be fooled, it is as hard as concrete. The blades on the metal runners, polished to perfection the night before, will slice through a misplaced finger like a knife through butter but they are the only things that will safely guide you down this beautiful run to the finish. The feeling of exhilaration, relief and sheer joy is overwhelming when I come to a halt on the matt at the finish in the charming village of Celerina, some three quarters of a mile away from the top. The sun shines and the faint waft of cattle from a nearby farmhouse add to that warm feeling and general love of life that is generated, I presume, by the huge amount of natural endorphins that have just been injected into my brain.

St. Moritz is a curious place. The first maps dating back to the early sixteenth century do not acknowledge its existence. Zuoz, Samedan, Pontresina all get a mention but St. Moritz, a tiny hamlet is of no importance. When the hotelier, Johannes Badrutt, in 1885 challenged his, mostly English, summer guests to come up in the winter for guaranteed sunshine and some fun on the snow and ice St. Moritz took off. The first guests were invalids seeking recuperation in the pure mountain air. A few good lunches at the Kulm Hotel and the mad idea of riding down the bends of a frozen river bank to Celerina on a tea tray seemed very appealing, became an organised sport and the Cresta Run was born in 1887.

Badrutt’s Palace or ‘Sanitorium Gothic’ (Image source)

This is why architecturally St. Moritz is so strange a town. The few genuinely old buildings are deluged by the massive sprawling hotels which come in one form or another of what might be described as ‘Sanatorium Gothic’. Add in a large amount of injudicious post war development and you get a sort of winter Las Vegas by the frozen lake where anything goes architecturally.

However, the indigenous architecture of the Engadine, which can be found in the many surrounding villages and valleys, is unique. In this day and age, it is easy to assume that Switzerland was always a country of rich, secretive bankers with a prohibitive exchange rate. In fact the opposite was so. Switzerland had no natural resources and was unproductive agriculturally. Its major export was mercenaries to the larger warring nations surrounding it.

For those not off fighting foreign wars, farming was vital for survival in these cold, inhospitable climes. The summer is only three months long and everything has to be harvested and stored during this small clement interval. Farming and the land was so important in the Engadine that the traditional house was based on a single prototype. Whether you were a small poor farmer or a rich aristocrat with a large amount of land, your house would be the same design. The only difference was size.

Because the climate in the Engadine is so harsh the timber chalet, which has become synonymous with the image of Switzerland, is too fragile to survive. This form of wooden building is associated with the lower altitudes of Switzerland, such as the Bernese Oberland. In the Engadine, the traditional houses are built of stone as timber just does not last in such a hostile environment. Similarly, because of the climate and the incredibly short season for growing and harvesting, the varied activities of farming all come under one roof and into one building. Going outside was, and is, often a perilous task and best avoided if possible. So, it may seem strange to live above the animals and the dung heap but that is what they did and some still do.

Typical Engadine farmhouse in Madulain (Image source)

The typical Engadine house is usually rectangular in plan but divided into two. On one side is the double height hay loft for storing the harvested grass throughout the winter and on the other is the living quarters. (Now that the Engadine is a mecca for the international art world, many of these impressive spaces have been converted into art galleries.) Externally the hay loft is visible by two tall double height arches infilled with leaky vertical timber boards for ventilation. The livestock occupy the whole of the lowest basement level, the stalls generally being under the hay loft. From the outside, the basement is accessed through a separate arch, usually on the gable end of the building but can also be reached internally by a stairs. This arrangement has a number of advantages. First the animals can be accessed directly from inside the house without having to go outside and secondly the warmth generated by the animals helps to heat the rooms above.

The ground floor contains the ‘saler’ which is a large entrance hall and storage room for the farm machinery of carts and sledges. This is also accessed from outside through an arch. The saler leads directly into the hay loft via a bridge or ‘talvo’ and to the side, off the saler, is the ‘stuva’ or living room which is the most important room in the house and is the only room that is heated by a stove. This is the most elegant room in the house also, sometimes richly decorated with carvings in the wooden panelling, and is used for family gatherings and entertaining guests. The ‘chudafo’ next door has an open hearth for cooking and for the smoking of meat. This is generally a dark and dingy room as the walls are covered with pine pitch. A hatch allows the food to be passed through to the stuva. Next to the chudafo is the ‘chamineda’ which is used as a store for seeds or other valuables.

Detail of Engadine farmhouse – note ‘sgraffito’ (Image source)

Above the stuva is the ‘chambra’ where the family sleeps. This is a simple undecorated room which is accessed by a ladder from below. Being situated above the stuva it benefits from the heat of the stove. As this is a room for sleeping, it typically has only a small window or even just a hole for ventilation. The rest of the first floor is accessed separately from the suler by a stairs. This large room called the ‘plantschin’ is for the farm hands to sleep in and again has access to the hay loft.

This pattern repeats itself throughout the Engadine and many examples can be seen in Zuoz, La Punt, Silvplana, Madulain and Pontresina. Externally the stone buildings are rendered and in the later cases a unique form of decoration called ‘sgraffito’ is used to embellish the facades and openings. (This was and is carried out by Italian artists who travel from across the border a few miles away.) As the positioning of the fenestration is designed from the inside to the outside, a charming sense of irregularity and asymmetry characterises the often impressively large facades of many of the buildings.

Clusters of these farm buildings form the ancient and charming villages. The buildings are oriented away from the harsh, hostile mountains and towards the village fountains. Each fountain is shared by a number of families and so the fountain is a place of social interaction. A highly decorated oriel window is often strategically placed on the facades of the buildings to ensure that a view to the fountain is always possible from inside the building without going outside.

Appreciation of the Engadine vernacular was slow as these old buildings were perceived, in the nineteenth century, to be primitive. The regular rationally designed facades of the new hotels rejected the roots of Engadine building for the new and what was considered sophisticated and cosmopolitan at the time. However, with the help of some enlightened architects and patrician families, some of whom had gone elsewhere to make their fortunes and then returned to the valley of their birth, an appreciation of the traditional building forms gradually increased. In the rest of Europe, there was also an increasing awareness and appreciation of traditional building patterns as expressed so well by Camillo Sitte in his 1889 book titled ‘City planning according to artistic principals’. In the Engadine, the architect Nicholas Hartman, amongst others, contributed to the appreciation of the unique Engadine way of building. In fact Zuoz, further down the valley from St. Moritz, became one of the first self-consciously historical towns in Switzerland, with its civic leadership ensuring that its unique older buildings were preserved.

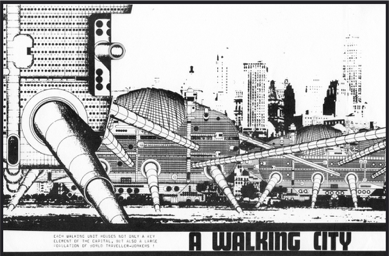

Now let us turn our attention to one of the more recent additions to the town of St. Moritz by one of its resident architects – the Chesa Futura designed by Norman Foster in 2001. The fantasy of ‘blob’ architecture started with Archigram in the early 1960s. Archigram was both a publication and a manifesto by a group of students at the Architectural Association (known as the AA) including Peter Cook, who produced the most lasting and famous images, and Ron Herron, amongst others. It was a group that firmly believed in the future and promoted alternative forms of living and building. Pods, plug-ins, balloons, modules and space frames all contributed to a temporary and flexible architecture that would transform the way we all lived. It was architecture’s riposte to Pop Art and was genuinely new and exciting. The projects were mostly fantasies and nothing was built that came close to the aspirations of the founding members.

‘A Walking City’ by Ron Herron and Archigram, 1964

However, a seed had been planted and in 1972 an obscure team of Richard Rogers (who had studied at the AA under some of the Archigram members) and Renzo Piano, an Italian engineer, won the ‘Beauborg’ Competition for a new museum in Paris (what is now called Centre Pompidou). At last pods, plug-ins, flexible space, temporary structures and expressive space frames, all originating with Archigram, could be tested in real life. Many British architects, including Norman Foster (who had studied at Yale with Richard Rogers and worked with him briefly at ‘Team4’) were deeply influenced by the ideas of Archigram. Later they became well known and branded as the British ‘Hi-Tech’ architects. It seemed like a genuinely British architecture that had its roots in Victorian engineering using the hard and shiny materials of steel and glass and rejected the sculptural forms of Corb and other brutalists that were in fashion at the time. Nicholas Grimshaw, Michael Hopkins, even James Stirling in his early years and later, Jan Kaplicky of Future Systems were all inspired by Archigram.

Part of the Archigram fantasy was to build rounded, irrationally shaped ‘blob’ buildings which technically could not be achieved in the early sixties. In the 1970s the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer and the German engineer Frei Otto had gone some way in pushing the boundaries of form. However, with the arrival of computer aided design (CAD) software in the nineteen nineties, three dimensional irrationally curved buildings could finally be designed and built. Blob architecture was achieved at last in 1999, with the aid of ship builders, in the Media Centre at Lords Cricket ground in London by Jan Kaplicky of Future Systems and closely followed by Norman Foster in 2001 in St. Moritz with his ‘Chesa Futura’ apartment building.

Chesa Futura by Norman Foster (Photograph by author)

It has been a dream of many architects for decades to build ‘blob’ buildings but how to convince a client to build one? Norman Foster is probably Britain’s most famous twentieth century super star architect and with that status comes some very large persuasive powers. He has also done a lot for the rehabilitation of St. Moritz and with his world renowned reputation he was able to convince the town that his ‘blob’ design was appropriate.

If we look up the Catalogue of Foster and Partners we learn that Chesa Futura’s ‘form is novel but is framed and clad in timber…’ It continues: ‘in Switzerland, building in timber is particularly appropriate in that it follows indigenous architectural traditions.’ As we have discovered, building in timber is not an indigenous architectural tradition in the Engadine valley as it is at too high an elevation for the material to last. We also learn from the Catalogue that ‘the larch shingles will respond naturally to the exposure to the elements changing colour slowly over time to silver grey’. Unfortunately, the larch shingles have weathered differentially depending on what slope on the building they are placed. This lends the building a sort of two tone effect which cannot have been anticipated in the original design. We also read that ‘in Switzerland, there is long tradition of elevating buildings to avoid the danger of wood rotting due to prolonged exposure to moisture’. This I do find a little far-fetched when applied to the Chesa Futura (or the Chesa ‘Potata’ as some disgruntled locals rather unkindly call it) because this building screams out its individuality and is so unusual, it cannot be mistaken for a traditional Swiss building. However, these are small criticisms and mostly concern the possibly misleading description in the Catalogue.

The now ennobled but surprisingly physically slight Lord Foster (he is keen cross country skier) allegedly has one of the apartments in the building and so is a St. Moritz regular. He has completed many good projects in St. Moritz, including the Murezzan Complex and the Kulm’s Ice Pavilion. However, I did think, as I was dancing next to him and his wife at one of St. Moritz’s well known night spots, that the text of his Catalogue would be more amusing if it abandoned some of the earnest ‘eco-babble’ and read something more like this. ‘We, at Foster and Partners, have always looked for a client who was prepared to build a ‘blob’ building on stilts, a bit like The Walking City of Archigram and here in St. Moritz we have found one. With regards to context, St. Moritz has no unified theme or homogeneity because it is a relatively new town based on the many fantasies that surround winter sports. Its character is therefore very eclectic, unlike the other well preserved traditional towns in the surrounding Engadine valley. In fact, it is the perfect spot to place our incongruously formed building in competition with other fantasy and trophy buildings that exist in the town.’

The modern movement, sometimes known as the International Style, was a worldwide architectural movement that was honest and naive enough to announce that a perfect and healthy life could be achieved through architecture and design no matter where a building was built. It was a way of building without boundaries and was ubiquitous. It most often completely ignored context, traditions, local climate and the vernacular and celebrated that uniformity. However, nowadays, it seems that we hide behind cloaks of sustainability or sensitivity to place so as to try and address some of the fashionable desires of the day. This building is not a product of a proclaimed international movement but it is however the result of a foreign idea that came from a different culture and it really has very little to do with indigenous models. Personally I find Chesa Futura rather exciting and, in the slightly mad, perverse context of St. Moritz, it is perfect. What other town in the world would not only countenance such a wilful form for a building, but also enable me, a rank amateur, to risk my life riding a metal skeleton head first on a three quarter mile long ice run every year?

Chesa Futura by Norman Foster (Photograph by author)