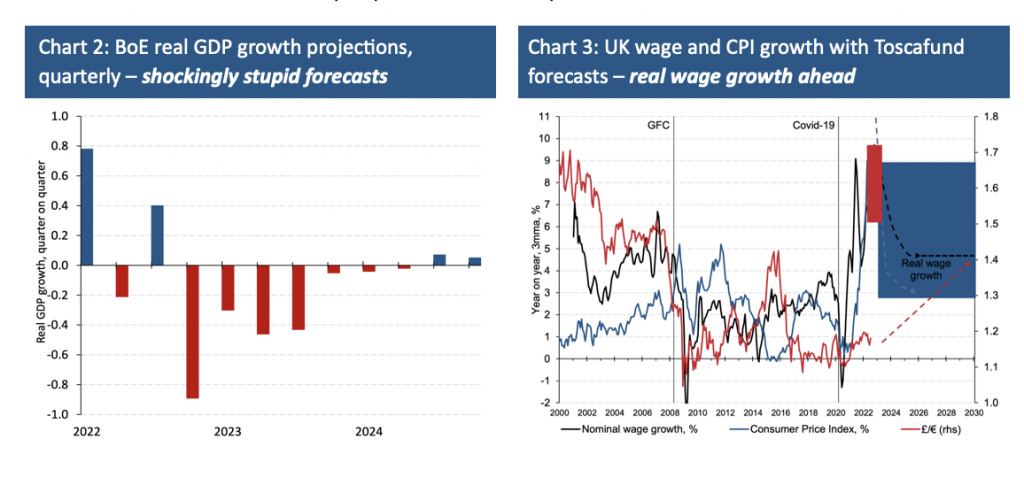

The Bank of England (BoE) projects the UK will ‘enter recession from Q4’. I will only accept we are heading into recession if the OBR says so when it next updates us in October.

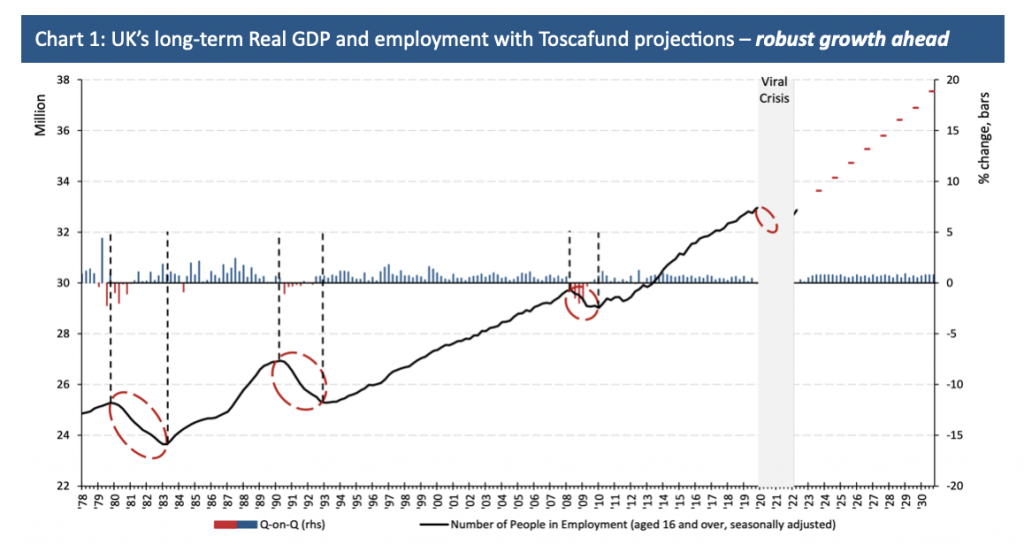

Only those close to 60 will painfully know what a real recession feels like. While 2008-09 was a difficult period for the UK it was nothing in comparison with what was suffered through 1989-92 and 1979-83. 1989-92 was not merely a sharp downturn in the average house price, but a monumental wave of repossessions. Contrast this with the forbearances of 2008-09, which saw banks tolerate mortgage arrears and allow payment moratoriums until economic prospects improved. With rates slashed, families in 1989-92 could only have dreamt of this happening as rates were kept stubbornly high to keep sterling within the EMU. That is until White Wednesday in September 1992, when the shackles were removed, proving what good ‘leaving’ can do.

Sterling’s competitiveness-lifting slump helped the UK economy to a speedier recovery than what might have been in 2008-09. Whilst sterling plummeted in 1979, such weakness compounded inflation injections from the oil price shock. By 2008, the UK’s move up the economic food chain to higher value-added sectors meant weaker sterling spelt greater affordability for UK services, not least to the Asian market, which had hardly been touched by the GFC (essentially a North Atlantic Crisis). Current weakness in sterling is actually one of its strengths.

1979-83 marked the dramatic end of large-scale employers of skilled manual men in heavy industries. Just as 1989-92 would see families thrown out of their homes, 1979-83 saw proud men, consigned to long-term unemployment, or at best, poorly paid under-employment.

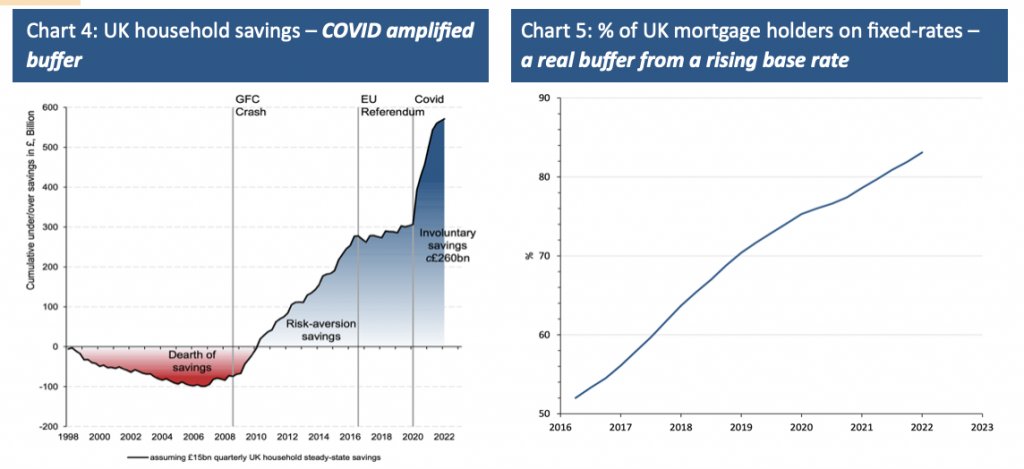

Chart 1 shows that my ‘timings’ of UK recessions – circled in red – based on UK labour market weakness, do not chime with the data for real GDP. Long-term data for real UK GDP does not align with what has constituted the UK’s chillingly real recessions of the past, while exaggerating the picture for others (2008-09).

It is worth quoting former Deputy Governor Charlie Bean from May 2016 regarding GDP.

“Measuring GDP, it turns out, is like trying to hit a moving target. As the economy evolves, so must the frame of reference for the statistics we use to measure it. Success requires not only understanding the limitations of traditional measurements, but also developing a curious and self-critical workforce that can collaborate with partners in academia, industry, the public sector and other national statistical institutes to develop more appropriate methods.”

“A curious and self-critical workforce”, six years on the BoE has yet to make these hires.

We just might see real GDP fall in Q2. Thereafter, I see little or no chance of what the BoE projects (see chart 2). Hiring is strong (chart 1) and so too are wages. At present, a great many pay awards are in double-digits, something we should all welcome (see Chart 3). Where does the BoE see a misfiring sector that would create a labour market reversal?

Our economy has fundamentally healthy property markets. Never have we had as much equity in our homes (this in addition to record high household savings) and been less exposed to moves in the base rate thanks to fixed rate mortgages (charts 4 and 5). Moreover banks, and the broader financial sector, have never been stronger. The UK economy is, in so many favourable dimensions, light years ahead of where it stood in 1979, 1989 and 2008.

So, to the Bank of England and its ‘economists’. You have no idea what a real recession looks like and will be proven so wrong. Cowardly, Bailey claims no culpability for being late to raise rates, deflecting blame onto events in Ukraine. This is a blatant misrepresentation. The last proper governor, Mervyn King, made clear in May that the UK economy had plenty of internal reasons for a much sooner monetary policy response.

Whether the BoE is sound or not in what it says, it can be self-fulfilling; sending the pound lower, pushing gilt yields higher, restraining business investment and hiring, and lowering personal consumption. To those fearful of this risk I say yes, there is a danger of such ‘unintended’ consequences, but no, they will not derail a fundamentally sound economy. Whatever the BoE may want to believe itself and persuade us of in turn, every sign we see heralding ‘hiring’, every new student and tourist flying into the UK, and export lifted out of it, thanks to a ‘weak pound’, flies in the face of the BoE because these only help lift the UK economy.

Let me close with a note on UK politics. The UK economy has proved itself resilient to political shocks. Liz Truss is on track to defeat Sunak (he should be the preference of anyone who wishes The Very Best for the UK economy) and thus de facto PM. The question then, is what would she mean for the UK economy? She would quickly see off Bailey, ratchet up in the yield curve (her fiscal largess would induce more stubborn inflation than a Sunak premiership). As for growth I will claim that recession predicted by the BoE can be dismissed whoever becomes PM – albeit a fundamentally more impressive outlook under Sunak.

If the BoE is correct it must be believed that Johnson’s successor will lose the next general election in May 2024. Were the UK to spend 2023 in recession, a win for Conservatives can be nigh impossible. If this is the case, winning the race to be PM should be deemed a poison chalice.

Now, I will introduce an element of proof by contradiction. Any descent into recession must have to be met with looser money. The challenge then to those who back the Bank of England is how on earth can the UK economy fail to respond favourably to cheaper money, and the near certainty of an ever more competitive currency, in the unlikely event the BoE is actually correct. If the BoE is indeed correct in its projections for dramatically weakened private sector consumption, then de facto CPI must come down sharply in 2023, thereby removing any brake on cutting.