The decade since the Global Financial Crisis has seen sharp increases in asset prices apparently driven by low interest rates. These low interest rates have been caused by quantitative easing, and lower interest rates have caused lower discount rates to be used in valuations, with the result that asset prices have been marked up.

Asset-price inflation in periods such as the dot.com boom and the pre-GFC housing bubble, has traditionally resulted in central banks setting higher interest rates as they aim to rein in speculation and inflationary pressure in the wider macroeconomy. However, the current round of asset price inflation has not fed into higher prices for consumers, and monetary policy has remained expansionary.

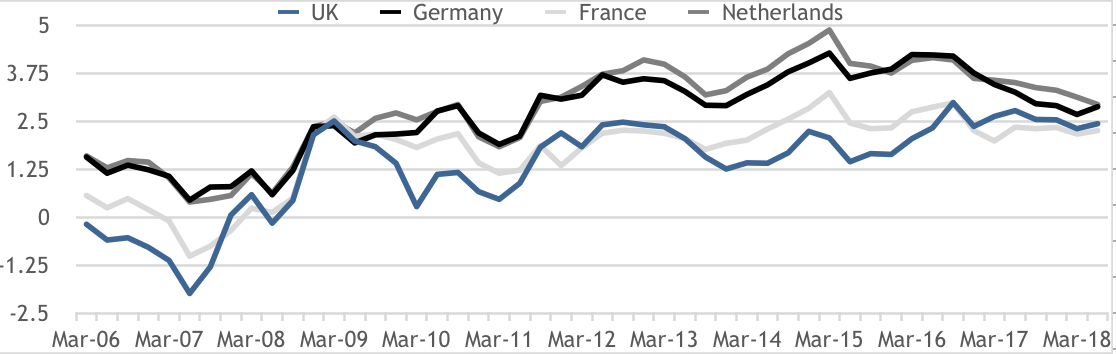

Property cap rates have continued a 30-year downward trajectory, following falls in both the nominal and real risk-free rates proxied by fixed interest and index-linked government bonds respectively. Figure 1 shows that, even though property cap rates have fallen since the GFC, lower interest rates have caused increasing spreads for property investors and made real estate an attractive asset. But is it really attractive?

There is now some consensus that rates will start to move upwards as central banks feel the economic recovery is sufficiently entrenched, allowing them to reverse quantitative easing. What impact will higher bond yields have on future property valuations?

Figure 1: Prime office spreads over ten-year bonds

In our last Property Chronicle piece, we developed the theoretical connection between real estate rents and inflation, real estate prices and indexed bonds (real risk fee rates) and real estate prices and fixed interest bonds (nominal risk free rates). But how strong in practice is the link between real estate cap rates and index-linked bond yields – and between real estate cap rates and conventional government bonds? Which is the stronger connection?

Rents and inflation

Let us start by looking at the relationship between rent and inflation. If property acts as a hedge over the long run, then rents will have a high correlation with inflation.

Property is often touted as an inflation hedge in the belief that rents will be regularly reviewed in line with inflation, and so over the long run the real value of rents will at least stay constant. Assuming that property costs also grow in line with inflation, the net rent will also hold in real terms.

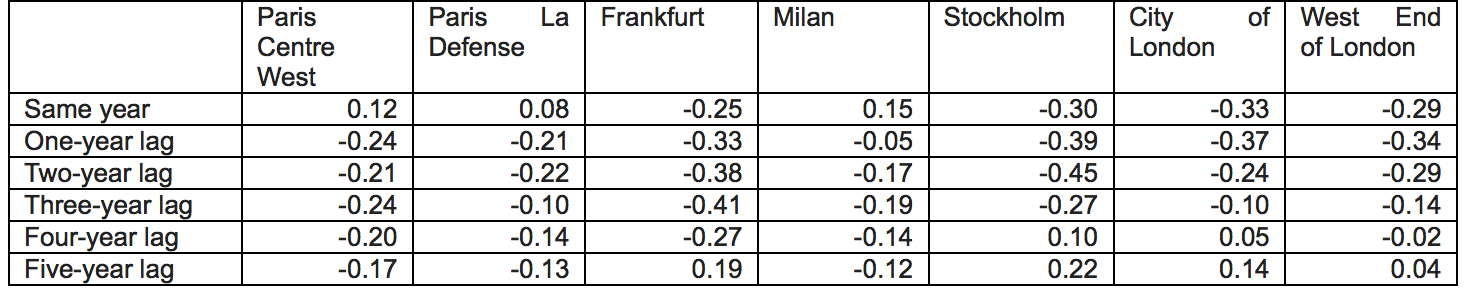

Table 1: Correlation between prime office rental growth and inflation

Rents may not respond immediately to inflation, especially in countries such as the UK with five-year rent reviews. However, many European countries have annual rent reviews linked to inflation, and so rent should move quickly in line with inflation. Table 1 shows that correlations are very weak and, in some cases, negative, even with a 5-year lag. This suggests that rents do not provide a good inflation hedge, as they do not move in line with inflation rates.

Confirming this, in 2010, the Investment Property Forum commissioned research that suggested that commercial property in the UK did not provide an effective inflation hedge and found greater correlation between rents and economic growth.

However, Bill Wheaton of CBRE and MIT wrote last year (CBRE Econometric Advisors,2017: ‘Has real estate been a good hedge against inflation? Will it be in the future?’) about US hedging elasticities, comparing movements in real estate prices and net income against inflation over almost four decades from 1978 to 2016. Taking a more robust statistical approach than simple correlations, he found that retail rents provided an almost perfect match with inflation. Industrial and residential property provided a partial hedge, whereas office assets had no hedging characteristics at all.

Wheaton also found that US property values provide a far better hedge than rents, with retail, industrial and residential assets providing a good hedge whereas office, while less effective, still offers a partial hedge. Property values have provided a better hedge as cap rates have moved down over the past few decades, allowing capital values to appreciate even as rents have not matched inflation.

Yields and bonds

The variable that connects rent and capital, of course, is the cap rate (erroneously but popularly known in the UK as the yield). Property cap rates have fallen over the long run, matching the long term fall in global interest rate. So, as Wheaton found, capital values have kept up with inflation, but income has not. What, in practice, has driven the cap rate down?

A recent study (Baum, Devaney and Frodsham, 2018: ‘Cap rate determination in European office markets: how does pricing respond to bond yields and market activity?’) looked at 24 office markets across France, Germany, Italy, Sweden and the UK between 1997 and 2017. Nominal bond yields have had a positive but not particularly strong relationship with property cap rates. However, modelling the relationship in real terms produces an improvement in explanatory power, suggesting that index-linked bond movements give a better explanation of the movements in cap rates. This is in line with the theoretical relationship we established in our last piece. providing evidence that investors should be concerned about the relationship between property prices and the real risk-free rate.

As a side note, the investigation also found that better investor sentiment and higher transaction volumes have led to lower cap rates, as confidence and strong activity have driven lower required returns and higher bids for property. Finally, major city office markets perform more in line with expectations and were more influenced by the variables tested than smaller regional markets. This may suggest that major office markets are more integrated with the financial markets.

The report also suggested there is some stickiness in cap rates, which take time to react to new information.

The risk premium

In the previous piece, we set out a simple framework based on the Fisher equation and the Gordon growth model to explain real estate cap rates.

Cap rate = real risk free rate + expected inflation + risk premium – rental growth + depreciation

The cost of equity is driven by the real risk free rate + expected inflation + risk premium. We have dealt with the first two variables. What has happened to the risk premium?

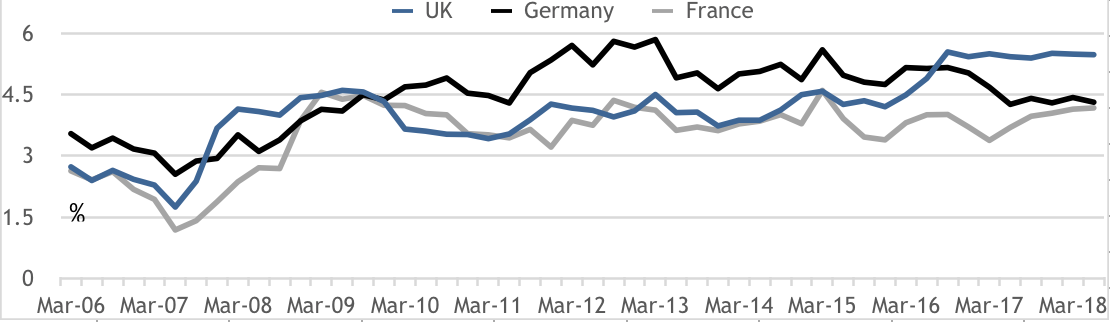

This is illustrated by Figure 2. The spread between the index linked yield and the property cap rate is a good proxy for the available risk premium. The average spread in the UK is around 4%. In 2007 this fell to below 2%. After the GFC this blew out to over 4.5% but it now stands at 5.5%. This suggests that there is some ‘wriggle room’ in current pricing.

Possible scenarios

There are three possible scenarios for the outlook on real estate pricing; bond yields stay low, real yields increase or inflation expectations surge.

- Index-linked bonds in the UK, Germany and France remain in negative territory. If this continues, the acceptance of a new low rate paradigm means that the all-time high risk premium may fall a little, leading to further growth in capital values.

- Real yields rise. The current risk premium has some room to fall – say by up to 1.5%. Values will be gently affected until that point but will begin to fall as this margin is eroded.

- If inflation expectations surge, there will be more focus on real estate’s imperfect qualities as an inflation hedge. Any doubts about this will transfer attention to the spread of cap dates over fixed interest bonds, which (as shown by Figure 1) looks acceptable at present but would erode with an inflation-fuelled rise in bond rates. The relevant question to ask in this scenario is how good an inflation hedge is your rental income?

Figure 2: Prim office spreads over ten-year inflation-linked bonds

The outlook for bond yields

What is the outlook for risk-free rates? The yield to maturity on ten-year gilts is far more driven by market forces than short-term rates, and had been falling for a considerable length of time before the GFC, going back to the 1980s. Some of this decline can be explained by lower inflation expectations, but real rates have declined as well.

It is easy to believe that that once quantitative easing is unwound then rates will return to the higher levels experienced before the GF. However, there is evidence that rates may continue their downward trend, regardless of quantitative tightening. Weaker economic growth, both globally and domestically, has led to weaker demand for funds for investment which, coupled with a continued global savings glut due to peak numbers of the working age population, means rates are low for structural reasons unconnected to the GFC.

As investors age, they will sell previously accumulated financial assets (including bonds) to fund their retirement, and an ageing population should push bond prices down and yields up. However, PIMCO (Fels and Tracey, 2016: ‘70 Is the New 65: Demographics Still Support Lower Rates For Longer’) suggest this will be offset by longer working lives and the reality that the bulk of financial assets are held by the highest-earning members of the population, who tend to continue saving in retirement. In addition, as savers age and approach retirement, they tend to reduce risk by allocating more of their personal portfolios to fixed-income securities, specifically government debt.

This suggests that interest rates will hold lower for longer, and PIMCO suggests demand for government debt will remain robust until at least 2025. Although they focussed on US data, the global nature of capital markets and common ageing demographics across the global gives some support to the same situation occurring in the UK and further afield.

Finally, we can reflect that Mark Carney sees 2.5% as the new normal for Bank of England base rates. The base rate rarely ventures above the yield on ten-year government securities, so 2.5% can be seen as an effective ceiling for ten-year rates. This is roughly a 100bps increase from present rates – not enough to damage capital values.

It is time for those of us who have been bearish on bond yields- and property cap rates – to think about revising our views.