The Japanese housing depreciation dilemma.

While Japan shares many characteristics of the West – a democratic political system and capitalist economic system – one area that distinguishes Japan as an outlier is the attitude the Japanese have to their homes. For many of us, in addition to the stability it provides, home ownership has traditionally been front and centre in our plans for building wealth and planning retirement. In Japan, homes have a rapid depreciation cycle, virtually worthless after 25-30 years; in fact, a vacant plot would be more desirable than a plot with an existing dwelling, in most cases. Land holds value, but dwellings do not.

How has this unique situation come about?

Japan sits on or near the boundary of multiple tectonic plates, making it prone to earthquakes and other natural disasters. Given that the building techniques are constantly improving resilience to natural disasters, many existing homes fall outside the continually updated safety regulations and are not trusted by the Japanese public. Japan, therefore, has a minimal second-hand housing market.

Exacerbating this predilection to view structures as temporary is the rebuilding effort after the Second World War. The quality of construction was poor in many cases, with little earthquake resilience and lacking features such as insulation. The practice of rebuilding every 30 years or so has lingered ever since.

What does this mean?

In the West, households typically build wealth through their home. With only a limited second-hand market to speak of in Japan, there is little prospect to build wealth through home ownership. With values depreciating over a 25-30 year time (a typical building life) and given the ever stringent seismic regulations, housing is seen more as a commodity to meet a need, rather than an avenue to wealth creation.

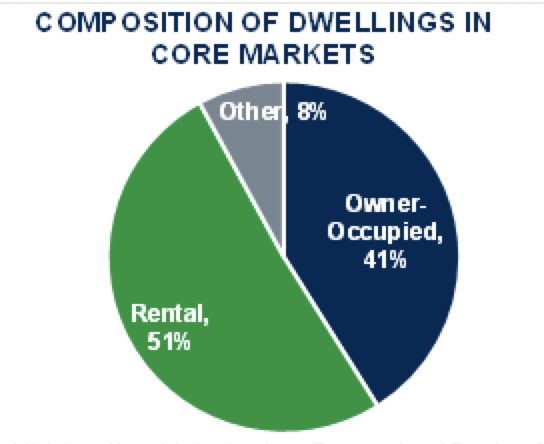

This situation has resulted in more of a focus on product itself. In Japan’s major centres, slightly over half of dwellings are rented. This higher proportion of renters gives landlords a larger pool of occupants to ensure their investment provides a return. However, there is more direct competition between new-build sales and rented accommodation, with the determining factor the property’s ability to meet the occupier’s needs.

The shortened property life cycle also has an unintended economic benefit for the construction sector, in that a 25-30 year lifecycle implies on average an underlying replacement of residential stock of between 3.3%-4.0% per annum, ensuring a base level of construction demand through the cycle. While this may create a sustained contribution to economic activity, it also undermines efforts on the environmental and sustainability front. The construction sector consequently produces large amounts of waste, even when materials are recycled, and consumes large amounts of energy, increasing overall emissions.

For investors into this market, particularly for multi-family, return expectations must account for discounting values back to site value in 25-30 years. For housing developers, it is key to offer a product that owner-occupiers will be willing to commit to for the entire economic life of the property (given the lack of second-hand market) or flexible enough to accommodate regulatory changes. This situation is clearly not optimal from an ESG standpoint. While efforts are underway to address the issue, it will be difficult to change long-term market behaviour. While the housing sector in Japan is very different to that in the West, there does remain opportunity for international investors, provided they understand the unique quirks inherent in this market.

Composition of dwellings in core markets