The interwar period in Britain oversaw the boom in the housing sector which resulted in the construction of a significant three million houses. In my previous article I explained how it is this boom which, amongst other factors, has been crucially attributed to post Great Depression economic recovery in Britain. The boom in housing was supported by a macroeconomic climate of cheap money, falling construction costs, increasing real incomes, and demographic changes. Renowned economic historian Stephen Broadberry has deconstructed the relative importance of each of these factors empirically. His research suggests that cheap money supporting the boom accounted for almost half of the increase in housing investment. Moreover, building societies played a crucial role in the transmission mechanism of cheap money boosting housing investment, since they had an influence over both the supply and demand of mortgage loans.

The role of building societies towards the boom in housing during the interwar period can be evidenced from the fact that from 1922 when they advanced £22.7 million to mortgagors and had total mortgage assets worth £83.7 million, they grew phenomenally and by 1938 had advanced £400 million with total mortgage assets worth £759 million. Such was the capacity of building societies to lend that even allowing for their hidden reserves, they had approximately lent out 50% of depositor funds. An important question to explore here is: how did building societies originate and what made them so successful?

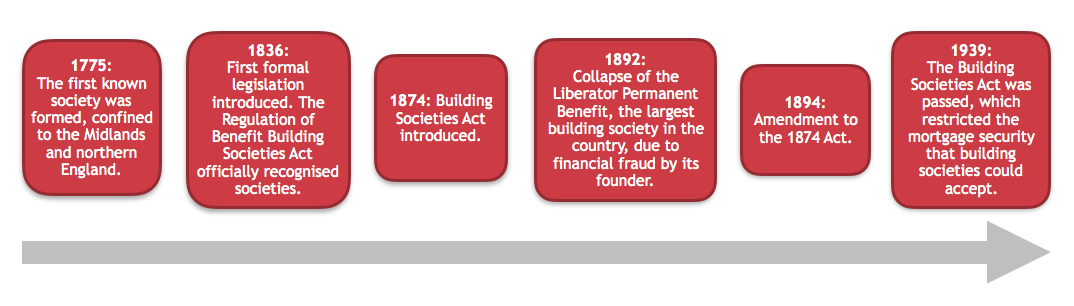

Figure 1: important events relating to building societies

Building societies were a uniquely English institution, a form of self-help organisation which were formed throughout Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries to improve the lives of working class people (see Figure 1). The precursor to the building society was the local building club, a cooperative association in which working class people pooled their savings to purchase land and materials for the construction of their own homes. Once every member had been housed, the club was wound up. The building club transformed into a building society with the realisation that the entire process could be expedited if the club could become a lending institution where people could purchase houses on the regular housing market.

This realisation was promoted by the growing purchasing power of the middle and working classes in Britain during the interwar period. Growing real incomes led to a demand for an institution to invest surplus incomes in, as well as a lending institution which would fund the construction of their homes. Commercial banks sourcing their funds through short term deposits were not suited to lend on long-term mortgages. Hence this void was filled by private individuals, insurance companies, trustee savings banks and building societies. Their success can be gauged from the fact that an Economist survey conducted in 1937 showed that between 1925 and 1936, building society advances witnessed a four-fold increase from £54 million to £194 million. Moreover, the annual number of borrowers attaining a loan under £500 increased by a significant 390% during the same time period. But what made building societies so popular during the interwar period?

What made building societies so successful?

Academics have pointed to some key factors which made building societies hugely successful during the interwar period. Firstly, the organisational structure of building society was very important. Being small and community-based made members monitor each other and ensure that subscriptions were duly paid and that borrowers were properly maintaining their houses. This is also reflected in the regular stream of repayments of building society loans.

Second, a significant proportion of members of building societies were not liable to tax at all which made interest on building society shares and deposits net of tax. This enabled building societies to advertise that their interest was ‘tax free’ heavily contributing towards their attractiveness. Professor Jane Humphries’s research on this aspect suggests that if building society tax rates are grossed up to the rate that would have been paid to yield the same real rate of return net of tax at the standard rate, the yield is far greater than that offered on consols. She is of the view that this differential is critical in understanding the inflow of funds in building societies during the first half of the 1920s. Treasury officials believed that it is these tax advantages which explained the rapid growth of building societies and led to their emergence from quasi-philanthropic local institutions to national financial intermediaries.

Third, as mentioned above, demand side factors of rising real incomes, reduced construction costs and the availability of cheap money especially during the 1930s also contributed to the growth of building societies. It is the combination of these factors which made building society manager Sir Enoch Hill estimate that between 1919 and 1937, ten million people were helped by building societies to provide accommodation for themselves.

Conclusions

Building societies offered chances of home ownership further down the social scale and captured a huge position for themselves within private and business communities. Interestingly, the popularity of building societies challenged the belief amongst joint stock bankers at that time who considered lending on housing as risky and unprofitable.

Today, activity in the mortgage market remains subdued. Key challenges faced by the housing market are the limited availability of suitable housing and the house price to earnings ratio being at a historic high, making affordability difficult. Despite these difficulties, building societies have held a high share in mortgage lending – one in three mortgages were approved by building societies in the first quarter of the year and they delivered half of the growth in the whole market. We can see that the interwar macroeconomic environment played a huge role in supporting the boom of building societies, but that this is hard to replicate today.