Seldom since its civil war and prior to that its battle for independence, has America’s internal future/fortunes been so vulnerable to the actions of outsiders serving their own ambitions. This time, however, it isn’t dealing with the conflicting colonial interests of the British, French, Spanish and indeed Mexican empires, but a singular Asian powerhouse. This is not, of course, the first time the region to its west has delivered a protagonist upon the United States. On this occasion it will not, however, be blindsided by a military strike from a small but aggressive Rising Sun – which it successfully sees off, as from December 1941 – but ever-growing monetary pressure from an economic Titan against which it will have no reasonable defence.

IChina’s efforts to establish the yuan as a global force – so as to build a deep credit market in it – can only come at the expense of investors in dollars and treasuries. There will, of course, be those claiming there are sufficient global vested interests for such dénouements to be impossible, or happen very slowly. One only has to look back at empirics to see how the sun can set suddenly on a once-dominant financial empire to quickly rise on the usurper; one to which those once loyal to the previous financial force then pledge themselves, even if only reluctantly.

There will, of course, be those claiming China is the one threatened economically – in which case, we all are. Let me at this point be very clear: I do not subscribe to such alarm regarding China. Rather than speculate on possibilities, let me consider realities.

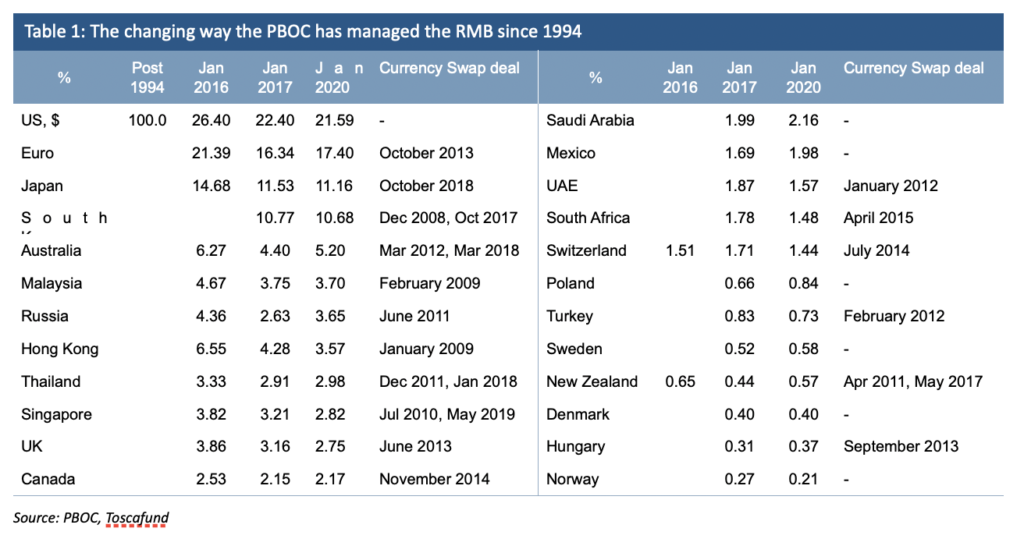

It is an actuarial axiom that China’s treasury holdings must fall in tandem with the dollars position in China’s currency management system. Here it is worth noting that until June 2005, the yuan was pegged perfectly to the US dollar, after which managed moves were allowed. The Hong Kong dollar continues to be a US$ facsimile, something which cannot last; a shock story for a piece other than this. Returning to the yuan, since January 2016 Beijing has diversified its currency management to include ever more other fiats (Table 1). The reality is that the dollar’s weight in the yuan’s management fell from 100% to 26.4%, then 22.4%, and stands now at 21.59%. More specifically, the yuan’s ever-expanding management basket currently boasts two dozen currencies. Awaiting another reweighting, even as soon as early 2022, one can be sure the dollar’s share will fall further and with it, China’s treasury holdings. The ever-lessening power of the dollar can also be seen in the way China has struck ever more currency swap deals with third parties; in effect disintermediating the dollar (see again Table 1). Against these ticking timelines I can confidently claim that each passing day is one closer to when the worlds voluminous savers can easily buy China’s sovereign debt, at the expense that is, of America’s.

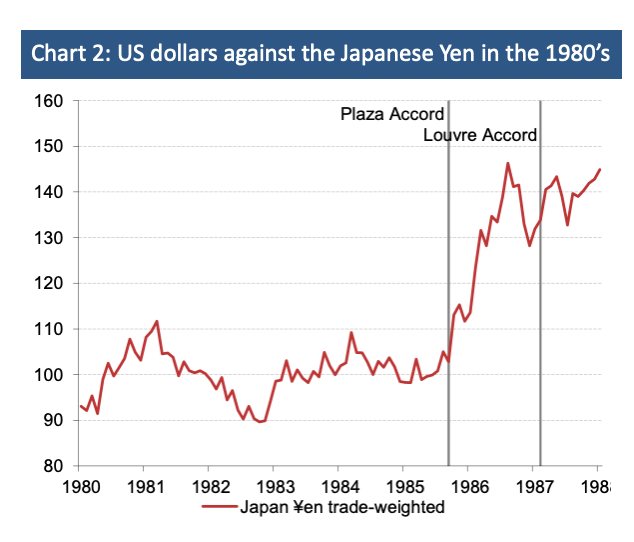

So much then, for China’s ever-more progressive devaluation of the dollar and opening up if its own debt market. The question is, has there ever been a precedent for this? Well, there is and there isn’t. There is because way back in September 1985, at the Plaza Hotel in New York, the dollar was devalued in a concerted way by what were at the time the world’s dominant central banks. Devalued at the behest of the US Administration and devalued most against the yen (the deutschemark rising too against the dollar, but much less dramatically). Rather than use a strengthening yen – chart 2 – to ‘draw in’ global savings, Tokyo made no effort to capitalise on its ‘surge pricing’; what was otherwise a loss of its trade competitiveness. The consequence is what we see today and have indeed witnessed for many decades, a moribund Japanese economy. So much then, for Japan’s failure to exploit a strong currency (other that is, than buy trophy assets around the world). I for one have no doubt that Beijing will miss the same chance.

As it manages the dollar ever lower against its own currency, China will open up its sovereign debt market to global investors; using these capital inflows to help grow its internal consumption (just as the US has long done). China will, in short, provide those around the world looking to save their wealth, with the yield and scarcity the US$ and its affiliates once did. A growing Sino-sovereign debt market will provide US treasuries with a rival against which they simply cannot affordably compete.

Let me return to the question of precedent. One could actually point to when the pound sterling was the currency in which so many global commodities were priced in, and in which savers all over the ‘known world’ as it was, chose to save a large part of their wealth. There was a time too, long before, when Roman coinage was the numeraire of trade and store of wealth. In between and before other such ‘gold standard’ specie existed. Going forward and sooner than is naively expected, the yuan will take on the roles the dollar currently holds almost exclusively. This is not a warning or a threat, merely a statement of time honoured, albeit far from frequent, monetary momentum.

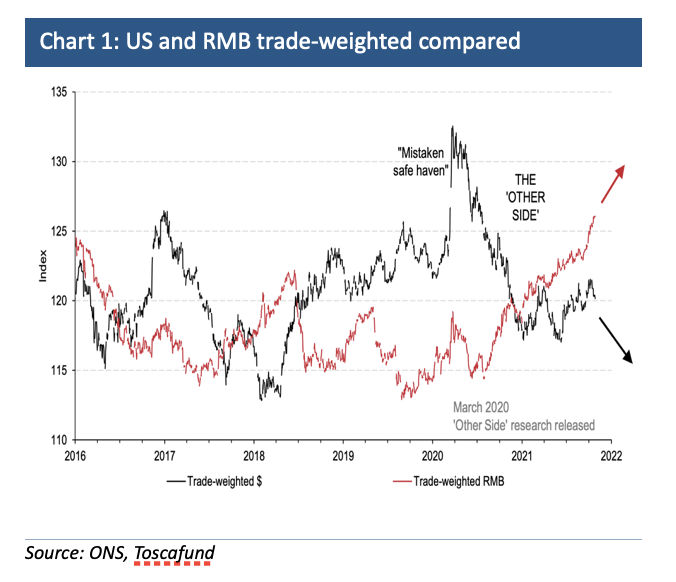

I must spend a moment addressing those who consider China an ominous military threat. To these I say it most definitely has no need for any such aggrandisement. After all, why should it engage in what would be certain to be troublesome military adventures, when it can deploy its vast monetary weight? Weight which can only get greater as its currency strengthens; strengthens in the measured but unrelenting way Beijing chooses (chart 1).