“Rain does not fall on one roof alone.” (African proverb)

Albeit debating the reasons along ideological lines, the world is getting to grips that climate change is an undeniable fact. Apart from pandemics, the subject is likely to dominate the global agenda, drive economic power shifts and migration.

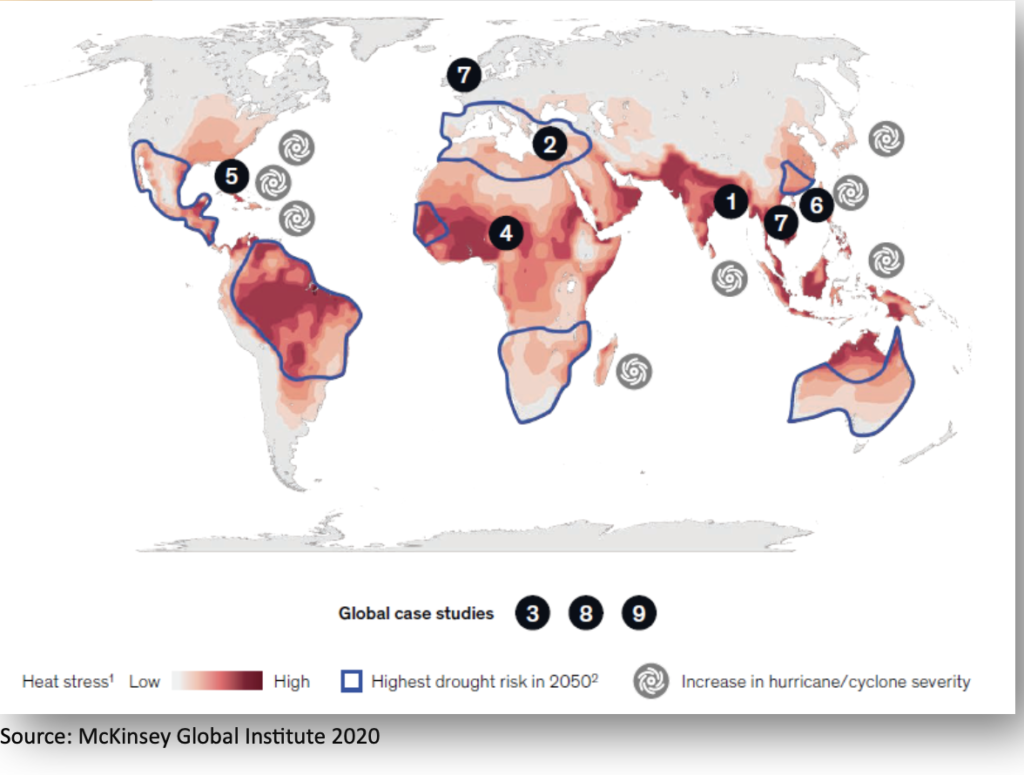

A recent research paper published by McKinsey’s Global Institute localises regions which will be most affected.

The paper also looks at scenarios which should keep the annual Davos crowd and everybody else whose job involves thinking ahead awake at night. The range of potential, or in some cases already materialising and very real issues indicates the global nature of consequences.

- Will India get too hot to work?

- A Mediterranean basin without a Mediterranean climate?

- Will the world’s breadbaskets become less reliable?

- How will African farmers adjust to changing patterns of precipitation?

- Will mortgages and markets stay afloat in Florida?

- Could climate become the weak link in your supply chain?

- Can coastal cities turn the tide on rising flood risk?

- Will infrastructure bend or break under climate stress?

- Reduced dividends on natural capital?

However, the map also shows regions around the equator being disproportionally affected.

Despite relatively low ‘contributory negligence’, countries in large parts of Africa will bear a major brunt of a changing and more erratic climate.

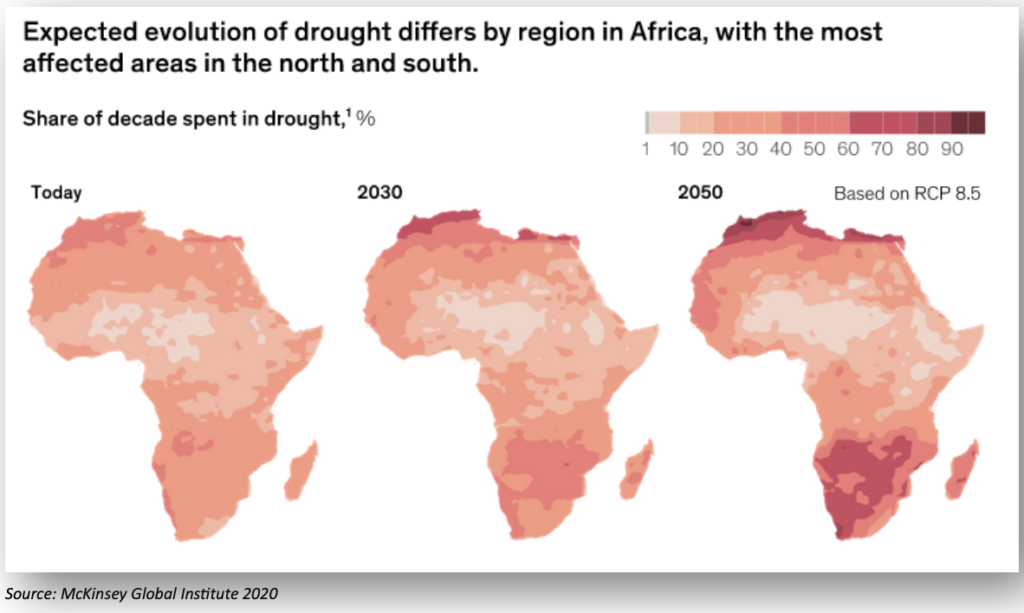

This will be reflected in rising median temperatures and increasingly frequent droughts resulting in a variety of adverse impacts.

Now, while discussions surrounding draught and heat stress impacts on agriculture and food security are in full swing, another pressing issue of equal strategic importance to a disproportional number of sub-Saharan African countries is often overlooked: electricity generation.

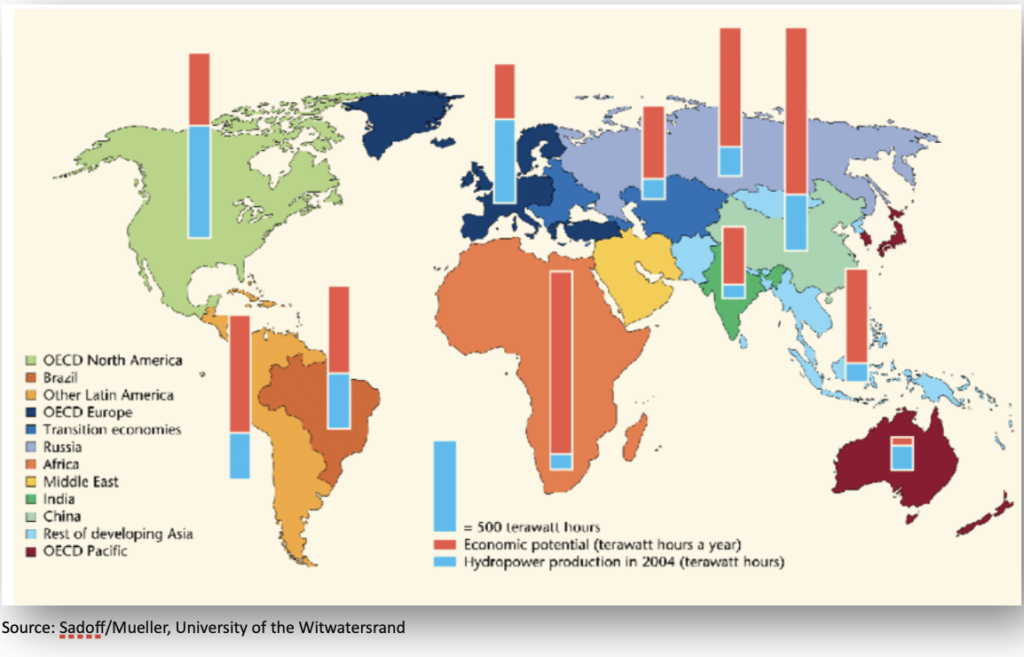

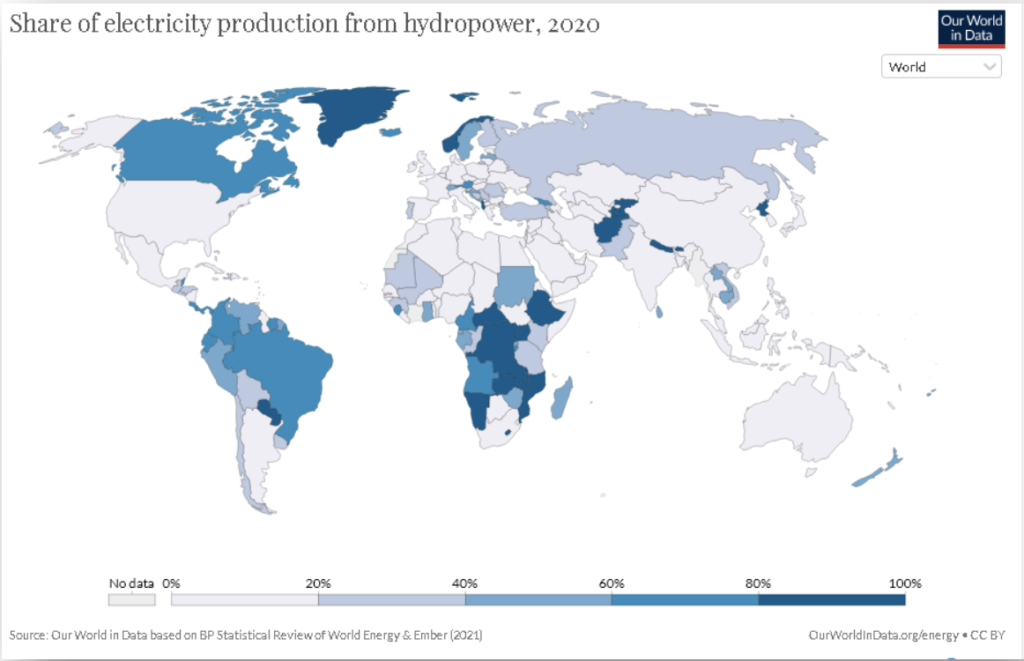

A significant number of countries in the region rely on hydropower as their main source for power generation. Looking at the underutilised potential of hydropower across the continent, this used to be a sensible decision during the heydays of dam-building a few decades ago.

As a result, in particular, countries in Southern Africa overwhelmingly rely on hydropower, which makes them increasingly vulnerable to lower and more volatile water levels in major rivers across the region.

Major countries in the region, like Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique have more than four-fifths of their installed energy production capacity concentrated in hydropower.

In Zambia, for instance, major existing installations like the 1080 MW Kariba North Power Station, constructed in 1956 or the 990 MW Kafue Gorge Upper Power Station, constructed in 1967, face significant rehabilitation works and technical upgrades needed for flood management. In the case of Kariba, efficiency drops to 40% during periods of low rainfall, undercutting minimum operating (water) levels required to run the turbines. Similar limitations apply to other hydroelectrical power stations in the country, where water levels of feeding rivers have been below long-term averages over the past few years, indicating a fundamental downward shift.

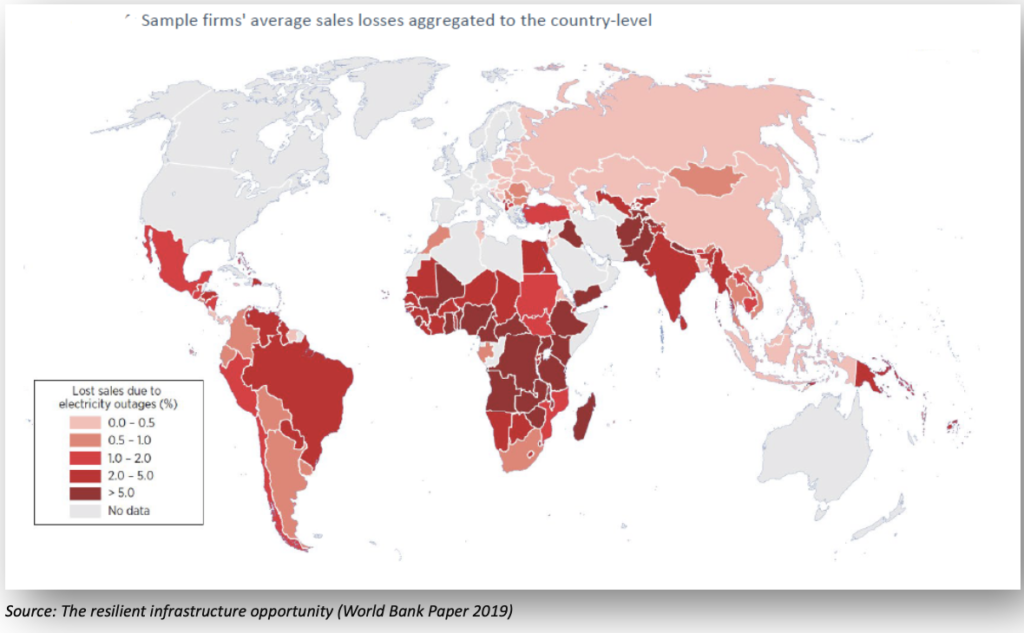

Increased supply volatility from installed hydropower generation adds to the already fragile power supply across the region, resulting in significant economic impact for individuals and businesses.

So, what’s the solution? While load management and increased intra-regional grid connectivity will help, a significant supply expansion at scale is required.

Given the increasingly volatile nature of hydropower, its ‘diverse side-effects’ on humans and wildlife, but also the increasing cross-border tensions due to water allocation disputes, like in the case of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, large-scale solar power has emerged as a credible and cost-effective alternative in sub-Saharan Africa.

But isn’t solar power that great idea which only makes sense as long as taxpayers shower it with heavy subsidies?

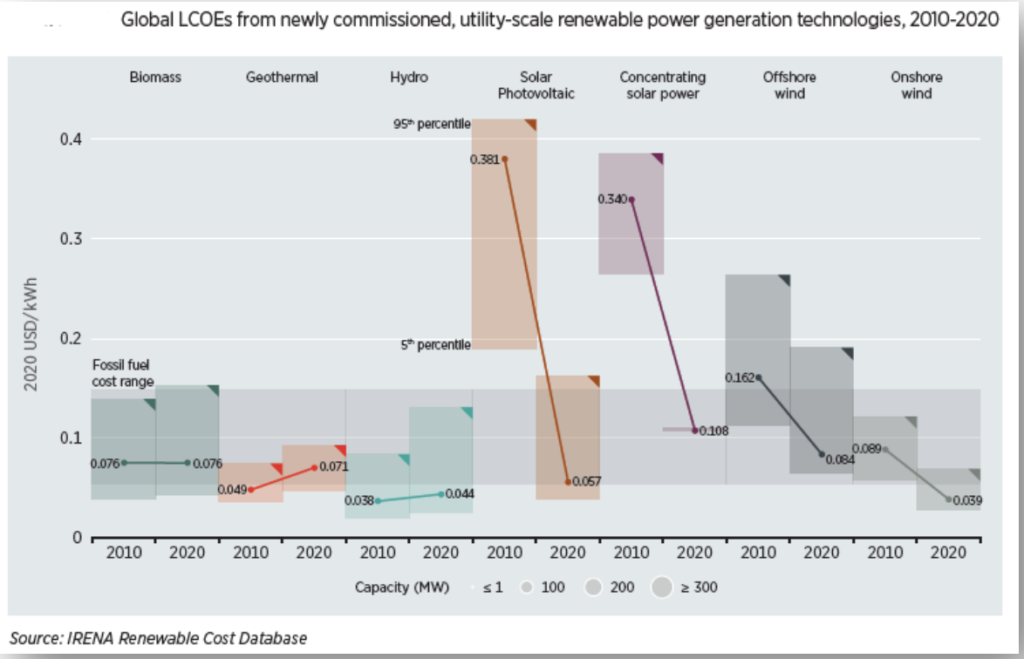

Not anymore. Costs have decreased significantly over the past decade, as low-cost manufacturing and economies of scale became game-changers for utility-size PV installations.

USD/kWh auction prices tend to be up to ~30% lower. It’s also important to note that IRENA calculations indicate significant cost advantages of solar compared to fossil fuel power plants, a trend which is likely to continue given discussions surrounding carbon taxation.

But wait a minute, this may all work out great by day, but we still need coal or gas-fired power plants to keep the lights on at night!

Actually, we don’t. A modification of traditional photovoltaic power plants, called concentrating solar power (CSP) solves that shortcoming of PV power plants, buy using solar power to run a traditional steam-powered turbine for (indirect) electricity generation and using a molten-salt ‘battery’ to store excess energy for up to 15 hours, enough to see sunrise without having to switch on the fossil-fuel generators. Despite its higher complexity compared to traditional PV installations, CSP plants have seen significant cost reductions and with auction prices as low as 0,07 USD/kWh, close to other intermittent renewable energy sources.

We are currently seeing several promising investment opportunities for utility-scale solar energy projects in Southern Africa with significant impact investment potential combined with attractive returns.

If you would like to learn more, please don’t hesitate to get in touch at mschwarzburg@briggmacadam.com