A single page of comic art can command prices of up to $1m – this isn’t just a market for sentimental collectors

“Everything you can imagine is real,” Pablo Picasso once said. Nothing could better sum up the appeal of collecting comic art.

In my previous two articles in this series, on collecting toys and comics, I concentrated upon the theme of the ‘accidental investor’: a collector who wanted things for their own sake, only to find that others now do too and values have risen. I am in the process of selling my comic and toy collections and, even though some items will not have risen in value, overall I expect to make a good return on my outlay even though I never once spent a pound with that intention. I simply bought things because I wanted them.

Comic art collecting is slightly different from comics and toys. While there are elements of the same fanboy/girl mentality, it seems to me that comic art is more ‘art’ than ‘comic’. Each artist is known because of their talent and ability to tell a story. Remember that they are normally part of a team: you have the writer, the pencil artist, the inker, the colourist and the letterer. Comic art, and American comic art in particular, is a production line; a pageantry of different players. The artist provides pencil art, the inker provides the definition for the art to be reproduced (these days electronically), the copy is coloured and the dialogue added. But it is the pencil artist who is considered to be the principal creative input. And while a particular comic artist may come to favour because of a run on a flagship title, such as The X-men or Spider-man or Batman, it is their art that shines through.

I have original comic art on my walls because I like to look at it time and time again. I love the intricacy of the layout, the expressions of the characters and the overall aesthetics of the page. And, as with any art appreciation, I can easily identify individual artists by their style, not only by the subject of the page. And, also, as with the collection of other kinds of art, there is a feeling of honour, or pride, or simple possessiveness in owning the original. Most people who love, say, Picasso, can buy all his art as prints for a few hundred pounds but each original sells for millions of dollars. People pay for the kudos of ownership.

And that is why, of all my collections, I feel that collecting comic art is the most akin to actual investment. The comic art market at the top end is dominated by investors and, from my conversations with auction houses specialising in comic art, shares the obtuseness of ownership and (non-)display where the most valuable pieces are bought and then locked away in hermetically sealed vaults until the time comes to resell at a profit. The right piece of comic art can command very high prices, of up to $1m a page. That said, the work of any new talent normally sells for a few hundred dollars. If you spot their potential at that point, before they become a fan favourite, that is where the profits lie, as the price of their stock rises quickly in tandem with their fame.

New comic art wasn’t always available for sale in this way. Today, artists retain their original pages, which are returned to them after the pages have been processed and published. Some artists then resell their art themselves, some appoint agents, and some keep all their work, but the art is theirs to do with as they wish. In the early days of Marvel and the revived DC Comics of the 1960s and 1970s, the companies retained the art pages and often stored them badly and haphazardly. The great artists of those days, such as Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, John Romita Sr and many more, didn’t get to keep their art. Their fight for their rights of ownership is outside the scope this article, but it wasn’t until the mid-1980s that the majority of artists were reunited with their work. I mention this because it was one of the drivers that created the comic art investment world of today. Markets need stock, and now the stock is no longer stored in warehouses, there is a very active market with numerous specialised auction houses, websites and dealers.

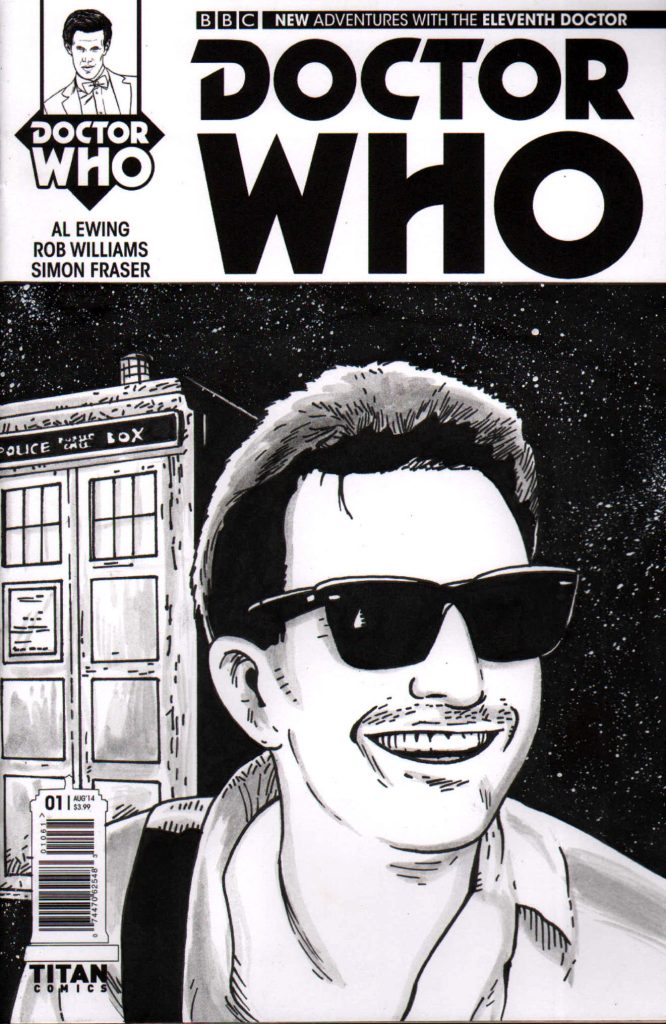

And as with any market, new opportunities arise. Some artists will take commissions to draw a special page for the buyer, although they remain unpublished – and published art is the most valuable. These may be reproductions of published art or ‘action’ pages of the buyer’s favourite characters or, as in my own Doctor Who page, they may include the buyer’s effigy. Some of these types of pages themselves become valuable over time in concert with the particular artist’s fame, while others may just be of sentimental worth.

These three articles on toys, comics and comic art have all focused on the overlap between collecting and investing. They are written from the viewpoint of a collector – the accidental investor. I believe that most collector markets start, as the name suggests, with individuals who get a psychological reward through ownership. They may make money if they ever liquidise their collections, but that is not the driver of the market. They collect because they are driven to do so. Investors, one would hope, are more rational. They can usurp the collector markets and create a new market of their own, which overlaps with the original but is more akin to any commodity market. Investment is simple: buy low, sell high. Toys, comics and comic art are just commodities and if an investor can read the trends of those markets, then they can become the alternative investments of today.