Market transparency determines the relative usefulness of different types of data. The application, veracity and appropriateness of comparable data are not universal.

Property valuation is deceptively complex; its appearance of simplicity belies the requisite skills and knowledge of the valuer for understanding the property market. As I wrote previously, comparison is the linchpin of all real estate valuations and is more than the simple use of transactional comparables but relies upon a plethora of other signposts that enable the valuer to gauge the market. The choice of signposts is dictated by data availability: different markets, of different economic transparency, will rely upon different data.

In a transparent market, the best data may indeed be a recent sale, whereas in a more opaque market asking-price information may be the chosen anchor for the valuation. Normally, the distinction between market types strongly reflects geographical or cultural differences, but the impact of Covid-19 has meant that the availability of data across transparent and opaque markets has been much more uniform internationally. All markets have seen stagnation in transactions, and so all valuers have had to look to other signposts to help them assess market value.

In any market, though, no good valuer would simply replicate the numbers from comparable sales and other data without further analysis. It may be that the market is static and thus prices will not have changed, or the market may be falling or rising. All valuations need to be placed in an economic context. Comparable evidence is the starting point but not the sole contribution; the valuer must assess what data is available to make a professional judgment as to price in the market today.

Valuation is a heuristic process that relies upon the expertise of the valuer. There may be systems and models to aid the valuer, but the crux of the process is interpretation of the market inputs that ultimately provide the valuer with their opinion of market value. Comparable evidence is part of this process, but without the expert judgment of someone who understands the nuances of the data, a valuation based solely on raw numbers could be erroneous.

International valuation standards should not be over-prescriptive in codifying the appropriate use of comparable evidence

The usefulness and reliability of property data has a hierarchy that will vary by country. This has long been recognised within the property literature, and in 2019 the RICS published a guidance note on the topic which adopted the broader definition of comparable evidence. This acknowledges the importance of all valuation signposts, including transactional evidence, asking price information, enquiry details of potential purchasers, market listings, market commentaries, market indices, government cadastres and the professional opinions of colleagues and other valuers.

The note states (at 4.4), “A hierarchy of evidence: It is clear that the valuer will need to use a wide variety of sources of comparable evidence and will require a high degree of skill and experience to analyse and apply this information. The ability to weigh (or rank) evidence collected according to its relevance to the particular property being valued is an essential part of the valuation process.”

The same matter was, coincidentally, central to the discussions of the European Group of Valuers’ Associations (TEGoVA) at its 2019 annual assembly before the publication of the RICS guidance. This resulted in a separate TEGoVA report, which expanded and developed the themes of the RICS guidance in a European context. As part of that study, in January 2020 a questionnaire was sent to TEGoVA experts and delegates to identify the role comparable evidence plays in property valuation and how the availability and use of comparable evidence varies between different countries and jurisdictions across Europe.

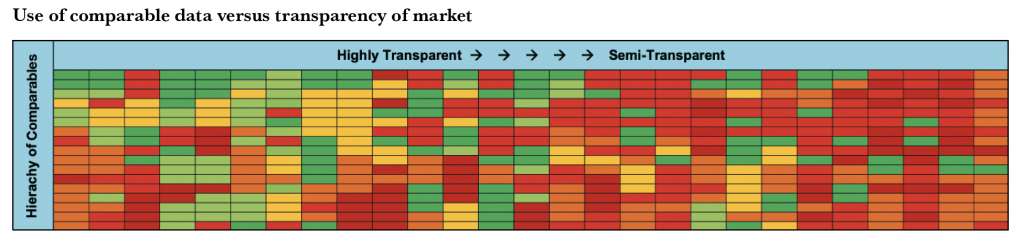

The results of the survey gave a broad indication that there was a correlation between the ranking of data sources and the transparency of the market in question. This confirmed the expectation that information which one country may consider should not be used as a significant signpost for value is, in another country, considered to be the principal signpost. Although the nature of the survey meant the results were not statistically robust, they did give a considered view of how valuers chose which comparable data to use in their particular market.

Using a standard traffic-light analysis based on the ranking of comparable data within each country (see table), it was possible to show that as markets become less transparent there are fewer available choices of comparables that can be used. This graphic illustrates that as markets become more opaque not only does the lack of comparable data increase (more reds), but the data considered most useful in transparent markets (greens and ambers) becomes less available and hardly used. Conversely, some data, for example asking price information, becomes more important and more frequently used as a principal signpost towards market value.

Each market has to deal with the data availability within a specific country. This means that valuers rely upon different data sources depending on where they practise. The application, veracity and appropriateness of comparable data is not universal. This implies that international valuation standards should not be over-prescriptive in codifying the appropriate use of comparable evidence as each data source could play a lesser or greater role depending upon the transparency of the market in question.

This underlines the central tenet of my previous article, which is that valuation is not simple. It is a complex process and valuers should be recognised for their skill and application in using comparable evidence, in all its forms, to determine an anchor figure and an understanding of current market sentiment to provide the client with the best estimate of market price: the market value.