In this very special series of exclusive articles for the Property Chronicle, Australian property legend Norman Harker reflects on his extraordinary 50-year life in real estate. He will pull no punches partly because, as he freely admits, Norman has a limited life expectancy of five years from December 2018 due to a diagnosed terminal blood cancer, which he has cheerfully accepted in preference to (in his words) “kicking the bucket without notice”. We are honoured he has chosen us to publish these brilliant, funny and incisive reflections of a lifetime in property.

Chapter 2: The pre-pubescent valuer – yearning for a moustache

Despite popular demand, I’ll continue from last week and won’t (as a certain presidential contender might put it) “shut up”.

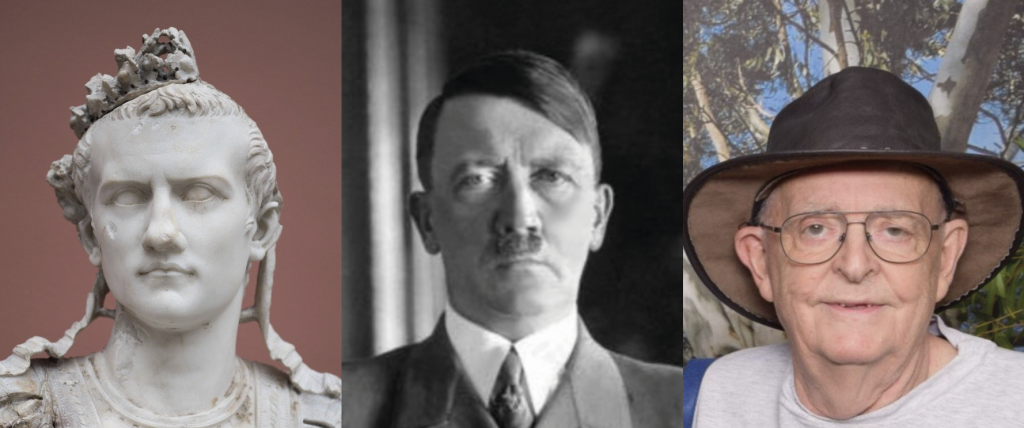

Psychiatrists and psychologists agree that people are the product of their background. Background formed the character of Caligula as the mad emperor, Adolph Hitler as an even madder dictator, and me as a valuer.

Three products of their times and backgrounds

People would often exclaim to me, when I would be, for instance, taking a legalistic view on the requirements of a valuation report, “Your father must have been a solicitor!” Almost true. He came from a working-class family that could not pay for ‘articles’ and so became a ‘managing clerk’. He drew up wills and did all the conveyancing for a small law firm, while a solicitor just signed the deeds.

A forward-looking investor in 1945, he saw that housing losses and troops coming home would cause property prices to rise. He bought up seven tenanted houses using his savings and mortgaging. But when did he get his monopoly set, I wonder?

He was meticulous in whatever he did and, many years later, when I was about to buy a house, he overlaid the estate plan on an old government map – to reveal that the terraced property spanned a refuse-filled gravel pit. Later those houses became a liability.

I had learned from Dad, without realising, that meticulous on-the-ground research forms the basis of valuation. Theory and data are essential but must be backed by shoe-leather-wearing-out knowledge of property and market. I will build your DCF model, but you must provide the data based upon your knowledge of the market and the property. I also learned not to argue with Mum!

Mum was a farmer’s daughter and at seventeen married a dashing young War Department soldier, who was ten years older. They moved to a seaside holiday and retirement town. Londoners went there on ‘kiss me quick’ holidays and day trips before the era of cheap overseas travel to Barcelona.

Londoners retired there not thinking what it would be like in winter or when the husband died. I saw where, how, and why not to buy property. One suburb was known as the best-lit cemetery in England.

My sister was born in 1952, after four boys in a row. Mum managed with the help of au pairs from a Netherlands family. We boys taught each other. My older brothers delighted in teaching me to swear. A frequently exasperated au pair made this a multilingual ability. I still swear too much, despite command of English.

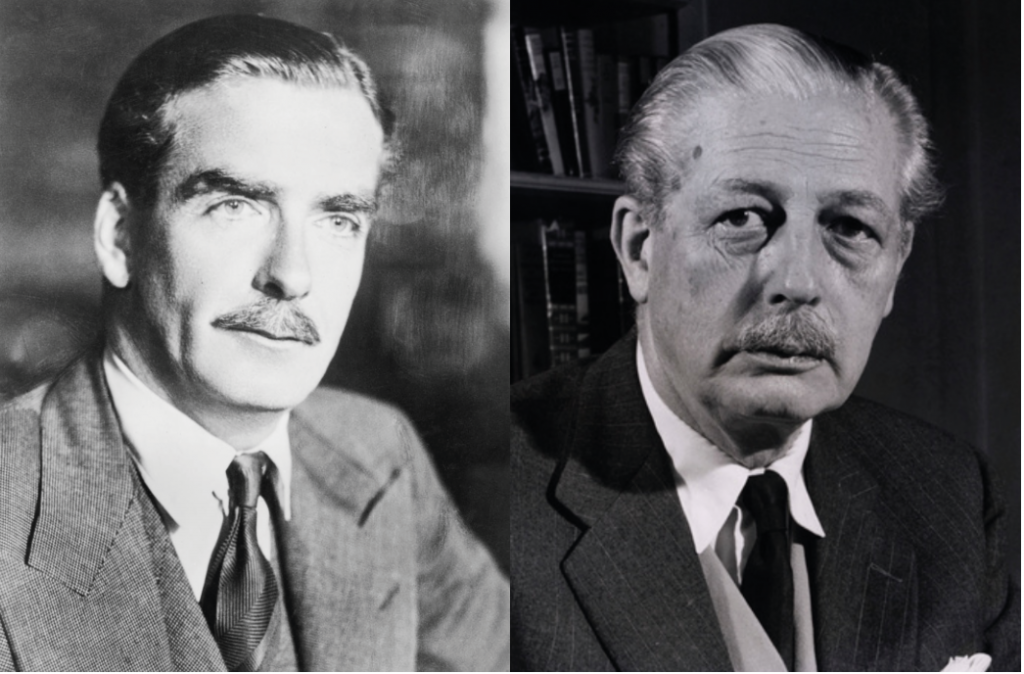

Cleaning shoes was a chore. I recall cleaning them on the Daily Mirror report that ‘Betty’ had called for Harold Macmillan to become prime minister. Anthony Eden had been too friendly with the French and had upset both the Egyptians and the Americans by sending troops, with nothing better to do, to the Suez Canal. You had to be elected and remain popular to be prime minister. It was the beginning of my political education – and taught me the importance of a moustache.

Early profound influences – I later grew a moustache to make me look older

I learned to swim at the age of five – with my older brothers, it was either that or drown. Swimming became my preferred exercise, especially after moving to Australia where the brass monkeys breed all year round. In England, summer started at the end of July and finished at the beginning of August. Regular early morning exercise kept me fit despite my sedentary job. Valuers need to be fit – and I met a future wife at a swimming pool.

Holidays were spent on my grandfather’s farm, and I wanted to be a farmer. But I was not in the male line of succession and had no family money. Later, in my teens, I toyed with the idea of becoming a gigolo, but I didn’t have the qualifications for that and continued on the path to becoming a valuer.

Despite sixteen years of heavy-duty valuation experience in London, I have inherited a rural empathy from those holidays with my grandfather. Valuers with a hard-working family background have a greater insight into market forces. But I generally find that such general statements are generally wrong and do not generally expects other to agree. This view formed part of my discussions with students in my time as a university lecturer. I frequently said: “I don’t expect you to agree with my views because I often don’t agree with them either.”

I argue with myself a lot in order to get an intelligent conversation going, and only worry when a third or fourth persona buts in.

Changes over time impact on people’s views, and views do need to change. John Maynard Keynes, my economics guru, was accused of changing his opinion. He retorted, “When facts change, I change my opinion – what do you do?” When I was studying economics and history at eighteen, JMK was a profound influence on me – eventually I was even able to grow a moustache.

Events impact upon opinions and that is part of the essential background to our profession of valuation.

Image sources: Photograph of Anthony Eden is by Walter Stoneman and from the Imperial War Museum; photograph of Adolf Hitler is from the Bundesarchiv; other images are from the public domain.