In this very special series of exclusive articles for The Property Chronicle, Australian property legend Norman Harker reflects on his extraordinary 50-year life in real estate. He will pull no punches partly because, as he freely admits, Norman has a limited life expectancy of five years from December 2018 due to a diagnosed terminal blood cancer, which he has cheerfully accepted in preference to (in his words) “kicking the bucket without notice”. We are honoured he has chosen us to publish these brilliant, funny and incisive reflections of a lifetime in property.

My memory for names is terrible. I have trouble with remembering my own. But that’s understandable, because I’ve been called so many over the years.

The legal mumbo-jumbo following is important to our valuation profession and the contents of their reports.

Roger Whittaker isn’t my favourite C&W singer, but his name (less one ‘t’) reminds me of a turning point in Australian law that had immediate impact on our profession. Australia’s highest court’s decision in Rogers v Whitaker (1992) HCA 58; (1992) 175 CLR 479 (19 November 1992) concerned professional negligence. In USA ‘informed consent’ and requirements of the medical practitioner regarding information provided dates from Major Walter Reed in 1900. But In the UK and Australia in 1992, the only authority for a ‘patient orientated’ view on the advice to be given was a UK 1985 dissenting judgement of Lord Scarman.

‘The Australian’ newspaper reported the fascinating fight of Maree Lynette Whitaker. She was made blind in both eyes when she had an operation to correct blindness in the other eye. It was accepted that surgeons did not generally advise of the very small risk of that operation. Maree Whitaker, then blind and without legal assistance, contended that the measure of advice given should not be what other surgeons did, but what they reasonably believed the patient would want to know.

The key finding of Australia’s highest court is summed up in this single paragraph:

“The law should recognise that a doctor has a duty to warn a patient of the material risk inherent in the proposed treatment; a risk is material if, in the circumstances of the particular case, a reasonable person in the patient’s position, if warned of the risk, would be likely to attach significance to it or if the medical practitioner is or should be reasonably aware that the particular patient, if warned of the risk, would be likely to attach significance to it.”

Our department’s legal lecturers, Diana Kincaid and Ralph Melano, confirmed the view that this would apply to all professions and to valuation reporting. We must add advice on risk or be exposed to claims if clients lost on a purchase where we had provided a valuation.

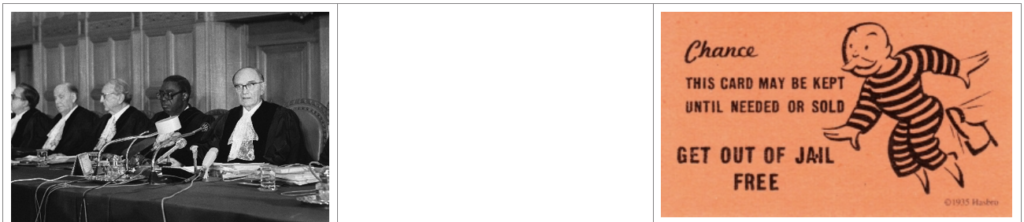

When apprehended by PC Plod and brought before the magistrates, I’d always pleaded ignorance: eg, “I thought zebra crossings were for zebras.” Magistrates mumbled, “Ignorantia juris non excusat.” (ignorance of the law is no excuse) before offering a £10 fine and next time taking a chance with a risk of going to jail for three turns of the thumb screws.

The magistrates’ decision: £10 fine or take a chance.

All lecture notes on valuation/appraisal report requirements were immediately updated and risk calculation was added. These days at that university, it would take 18 months to change lecture materials. We contacted the Australian Property Institute and they agreed to produce continuing professional development (CPD) modules on risk, including ones led by lawyers.

These became compulsory later, as did CPD itself when professional indemnity insurers and protective legislation wouldn’t cover the profession and/or its members unless risk training was undertaken.

“Time flies like the wind and fruit flies like bananas – it was a vicious circle”

Meanwhile, time flies like the wind and fruit flies like bananas – it was a vicious circle. Our department was moved to a yellow brick amalgam of High Schools and TAFE at an old naval base far away from the sea!

A few years later, admin found an old mental hospital for us. This was a good idea. My ‘cell’ in the old locked ward made me feel quite at home. Public transport was almost non-existent. But universities are for admin whose own offices were next to a main railway station. Senior admin had headquarters (‘bulldust central’) in a secluded motorway-accessible location 50km away, as far away from the students and the academic staff they administered as possible.

I’m sure that’s me on the stepladder of Vicious Circle – Jacek Malczewski painting.

My developing skills in Excel were barely tolerated and given no financial support. I still had to account for 36hrs for 48wks a year. This was to be made up of ‘teaching’ (‘education’ was not in admin’s vocabulary), ‘relevant’ research, and ‘recognized’ publication. Admin, judging people by their own standards, thought academics were lazy and only worked from 9:00 to 5:00.

Involvement with the API over 12 days every year for 20 years was voluntary and not counted. Nor was preparing the materials. They never did keep up with my needs for the latest computers and software or count the hours of educating myself on use, which were all essential to staying ahead. .

Student societies were on University property and came under the control of a new Dean. He merged the vibrant Land Economy Society with the accounting students’ society. The new society failed after one year – chalk doesn’t mix with cheese.

Land Economy chalk + Accountants’ cheese = Ughhhh!

Students were expected to attend (sometimes) and live at home or do other work the rest of the time. The best with high motivation, who incidentally were mainly female, still achieved superb results by maximizing opportunity.

On one occasion admin decided that academics should be at different locations from the students. Course-co-ordination was voluntary. I put my foot down with a firm hand and said, “OK! But I’m resigning as course-co-ordinator because I can’t do the job properly by telepathy.” An office was found.

“I put my foot down with a firm hand”

Admin later decided to control courses. Groups of (mis)assembled academics only provided units that fitted ‘one size fits all’ awards. Entry standards were lowered to admit more students so that the University got more from government to cover costs. Attrition rates were concerning. So too was the academic’s peculiar concept of failure to reach a minimum standard. Standards plummeted. Academics weren’t resourced to remediate lower standard entrants, both local and International.

Admin, with no professional property qualifications, decided that ‘real’ academics were to comply with their dictates on detailed content and assessments, I decided I could not to prostitute my professional integrity and resigned. From what I’ve seen and been told of subsequent developments, I know I made the right decision.

Footnote:

Maree Whitaker later challenged the Australian Tax Office who wanted to tax her awarded damages. She took that up to the highest Australian court. And won! You just have to admire that woman.