In this very special series of exclusive articles for the Property Chronicle, Australian property legend Norman Harker reflects on his extraordinary 50-year life in real estate. He will pull no punches partly because, as he freely admits, Norman has a limited life expectancy of five years from December 2018 due to a diagnosed terminal blood cancer, which he has cheerfully accepted in preference to (in his words) “kicking the bucket without notice”. We are honoured he has chosen us to publish these brilliant, funny and incisive reflections of a lifetime in property.

Chapter 8: A matter of chance – striking lucky

I had started my career at the bottom of the pile – although I was generally a pile in the bottom. ‘They’ say you make your own luck. I wish I knew who ‘They’ are, because in my case it was pure luck that saw me in the right place at the right time under the right people.

For the cricketers pictured above – that wasn’t a matter of luck: England were bound to lose because a) it was Bradman and b) Gubby was short-sighted, wore black shoes, wore his belt too tight, and parted his hair funny.

But to return to my surveying career…

At the top of the pyramid at the British Land Company was the charismatic John Ritblat (JHR). He had somehow managed to pass the exams to become a chartered chappie but had promptly forgotten, as useless to him, most of what he had been required to learn. His abilities were not in the chartered chappies syllabub.

His personal syllabub was:

1. Engineering ‘sale and fleeceback’ transactions (we called them ‘fleecebacks because rent was above rents on open market lettings);

2. Novel (at the time) company transactions including a reverse takeover that led to the acquisition and control of the British Land Company;

3. Selecting and motivating the key people in the organisation.

Our leader’s syllabub:

… which was made up of sale and fleeceback transactions…

… plus reverse takeovers and motivation

From my viewpoint, JHR’s best decision was appointing the late David Palmer to handle valuation and other professional instructions. We knew David as DWGP, short for David William George Palmer. Without doubt, he was one of the best brains in the profession and a born leader who earned loyalty and respect and brought out the best of others’ abilities.

What was notable with this leadership was that most of those people he appointed rose to become partners. At one point five out of 12 partners were his appointees and several others went on to become partners or achieve great things elsewhere.

It wasn’t necessarily because of their abilities. We know, in my case, that those abilities were limited to playing monopoly and living up to my grandfather’s advice, “Why be awkward, when with a little more effort you could be absolutely bl***y impossible?”

In early November 1973, I looked at the latest balance of payments release and immediately changed my trousers

One example of DWGPs modus operandi will suffice. (Note here my useless ability to use a language that no one ever was born to speak).

In early November 1973, I looked at the latest balance of payments release and immediately changed my trousers. I went to see DWGP and explained why I thought the UK was ‘up the proverbial watercourse without means of propulsion’.

Up Shush Creek (note absence of paddles):

The problem for us was that most of our valuations were for balance sheet purposes and would be dated 5 April 1974, by which time the excrement would surely have hit the air circulator.

The market was living in cloud cuckoo land and had not realised that the impacts of the Yom Kippur War on oil prices would produce far worse trade figures and a Bank rate well above the then record 7%. The coal miners were squaring up to take on the Heath government, whose political survival would be in doubt. DWGP left the room for a short time and came back wearing what could possibly have been a clean pair of trousers.

He then said, “Write me a memo of less than a page summarising what you have said and what we should do.” I did this within the hour.

In a nutshell – DWGP took all the criticism and derision but refused to accept the praise. That is a recipe for loyalty and respect

DWGP took my memo and said, “If you agree, I am going to circulate this with my name instead of yours and I’m going to add that no valuations will be reported formally or informally unless cleared by me.” I agreed it would be better coming from him on the grounds that I was a devout coward!

The memo was circulated throughout the firm that evening and DWGP was subject to ridicule and called alarmist by nearly all who read it.

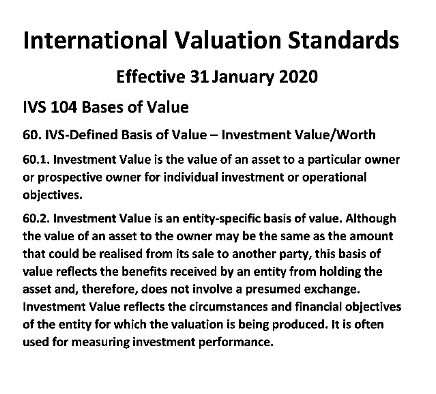

The secondary banking crisis hit in January 1974 and commercial property became almost unmarketable. One major firm, prepared valuations ‘on the assumption there is a market’! Also, at that time the concept of ‘investment value’ was born.

Is it worth it? (often used in times of desperation):

When the collapse hit, DWGP was praised for his foresight. He then issued a memo saying, “You should be aware that my memo of November was in fact authored by NJH, who agreed that it should be circulated under my name in order that it should carry some weight.” He failed to mention my cowardice and the bad English that he had corrected.

In a nutshell – DWGP took all the criticism and derision but refused to accept the praise. That is a recipe for loyalty and respect. These have to be earned and cannot be demanded.

Meanwhile JHR was offloading as many properties as he could to buyers, who at that time rarely employed valuers to advise them on purchases. When the crash came, his company barely survived, and even then, it was because it was regarded as too big to fail.

For months afterwards, members of the firm kept on asking me to turn around. After a couple of weeks, it was explained that they were just market forecasting by seeing if I was still wetting myself.

Checking the state of the market:

In December 1975 business rents control was removed by a Labour government and…

The young bull:

But that’s jumping ahead to another effort at putting you to sleep.

Image credits: Henning Schlottmann (shop window); Charles Esson (sheep shearing)