Originally published April 2022.

Land prices should now out-perform other asset classes, especially when compared to their underperformance during the previous period of deflation, argues this writer.

In November I suggested that inflation would continue, rather than being merely transitory. Since then, we have seen US inflation rise to 7% (for the year to December 2021, US Bureau of Labor Statistics). The Federal Reserve has now retired the term transitory and accepted that we are seeing persistent inflation. This short commentary looks at the likely returns to landowners in an inflationary environment.

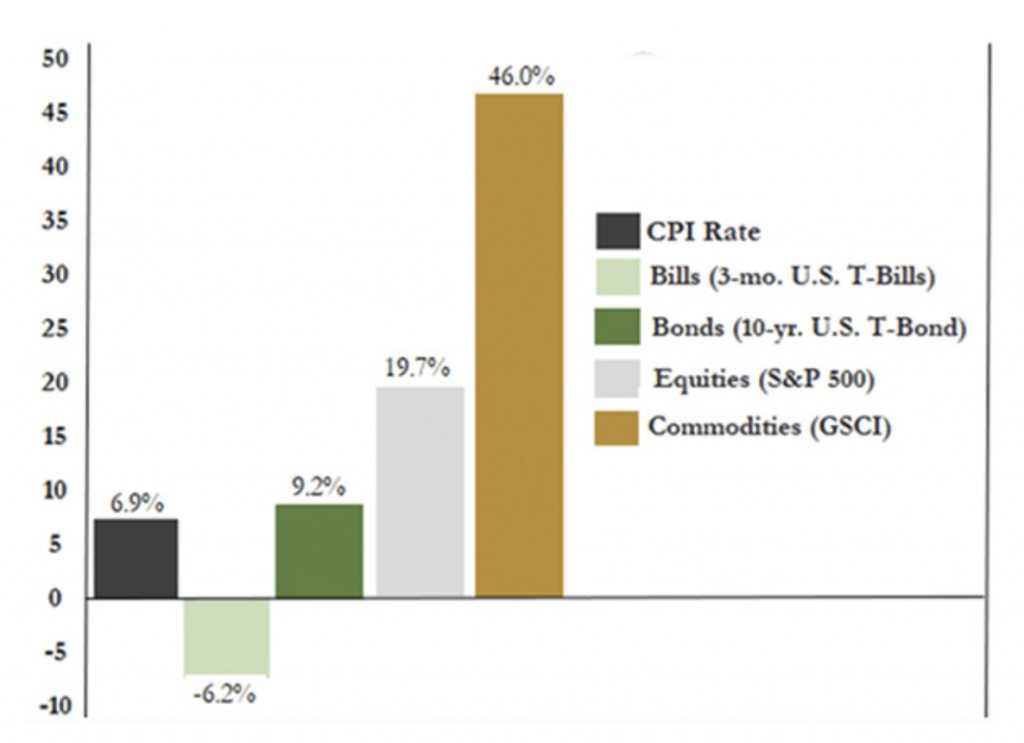

Prices of commodities, including farm produce, rose more than 40% in the past year, well ahead of equities at 20% (see the graph below). I believe rural land prices are likely to capitalise these commodity price gains. More generally, I think it is likely that land may out-perform other asset classes over the next 5 to 10 years, as some types of land have under-performed over the past 10 years.

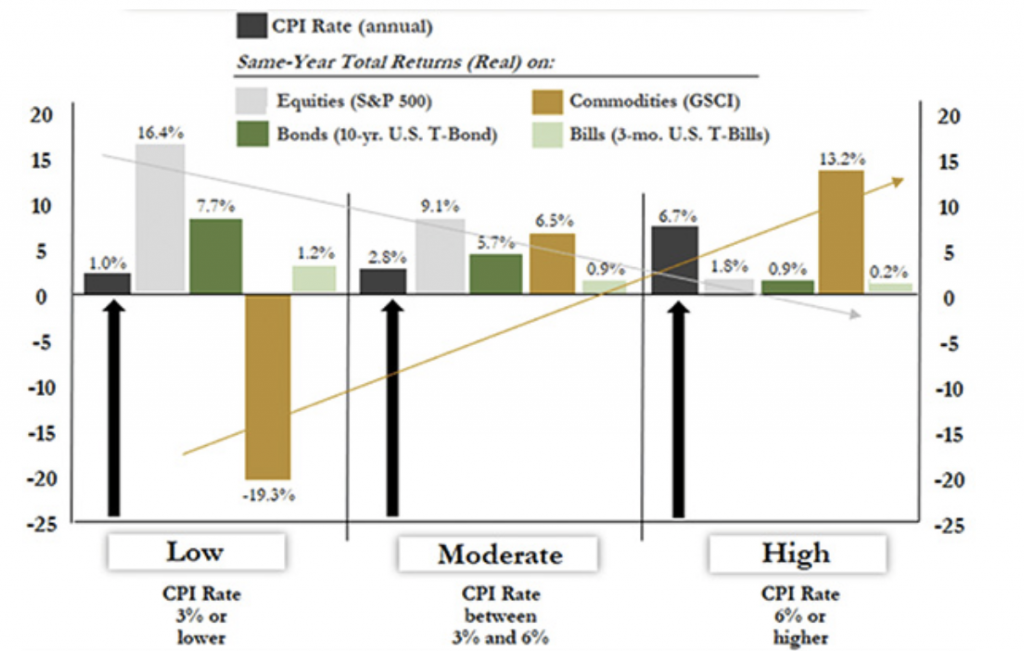

Real total returns on US asset classes amid higher inflation rate

Life in the 70s – amid inflation

In the second half of the 1970s, in a similarly populist political and economic policy environment to today, inflation in New Zealand averaged 14.8% pa(RBNZ inflation calculator – compound average annual rate of inflation). In this context, when mortgage interest rates were 18% to 20%, I was puzzled when my father explained to me that buyers and sellers valued farmland in our valley at a 3% to 7% cash flow yield “…and always would”.

How could farmers like him justify borrowing money at 18% to invest in land yielding 5%?

His logic was that since food commodity prices are correlated with inflation, land prices would capitalise inflation, generating an approximate 15% annual capital gain. Plus, since the technologies of the green revolution were in full flood in the 1970s, landowners were able to increase production (growing capacity) by up to 4% per year AND develop their land to generate a further, say, 4% annual gain in real revenues. My father could assume these gains would capitalise into the land values. This enabled him to budget annual capital gains of: 15% + 4% + 4% = 23%, implying total returns, including 5% cash flows of 28% – much higher than the cost of even 18% mortgage financing.

He did not avoid some cash-flow challenges along the way (sometimes it was a struggle to pay the school fees). However, he came out of that period having not only expanded our landholdings, but also having bought out the other family shareholdings in Craigmore Station.

To put this example of inflation financing in context, and before you conclude the Elworthys are completely reckless, it is worth noting that landowners and their bankers do not expand farms using high LTV ratios. Few farmers take on more than 30% or at maximum 50% debt against their assets. Therefore, my father had the support of the cash flows (and capital gains) on his existing less-leveraged landholdings to support expansion.

The fact that farmers and their banks are conservative in this way is one of the reasons land prices lag commodity prices, especially after a period of deflation. It is a chicken and egg behaviour. For example, in the NZ pastoral sector right now, where land prices have not risen for 10 years, farm cash flows have risen to an unusually high 6% to 12% of asset value (steady improvement always occurs in farming over the long term). However, despite the high cash flows, land prices have not ‘“aken off’, because few NZ farmers have unlevered equity with which to go out and buy land (in part because of central bank capital restrictions on bank lending).

In Australia this cycle is now further ahead. As a result, rural land prices responded to (also) bumper returns by rising 26% over the past year (Australian Financial Review).

Once a land market takes off, and capital is being ‘created’ by rising collateral values, then land prices will rise until landowners, thinking like my father, feel those prices have reached their upper limit. Land prices may then pause until the cycle repeats again. Craigmore calculates this behaviour may lead to a 50% to 100% rise in the value of prime NZ pastoral grazing land over the next five years, as long as commodity prices remain strong.

What next?

The graph below shows asset class returns for differing levels of inflation from 1971-2021. If inflation is higher than 6% then, if history is any guide, commodities and then land following, should significantly out-perform other asset classes. Whereas, if deflation returns, commodity prices may under-perform (and not boost land prices).

Real total returns on US asset classes under low, moderate and high inflation rates