… was a famous quote of appreciation attributed to Martin Winterkorn, Volkswagen’s former CEO, when closing the door of a KIA sedan at a car exhibition a few years ago. While Mr Winterkorn moved from the boardroom to the court room battling accusations in the wake of Volkswagen’s emission scandal, the automotive world’s attention shifted from the ascent of Korean car manufacturers to their counterparts in China.

Reading through Tom Stacey’s recent ‘China is on course to build the best cars in the world’ article in The Property Chronicle, I couldn’t help but consider what that notion would actually entail. Considering the authors argument of past innovations from safety innovation in Europe (electronic ABS introduced for the 1978 Mercedes S-Class), mass production in the US with Ford’s Model T and (lean) manufacturing excellence first introduced by Japanese carmakers, I was wondering what would drive China’s presumed rise?

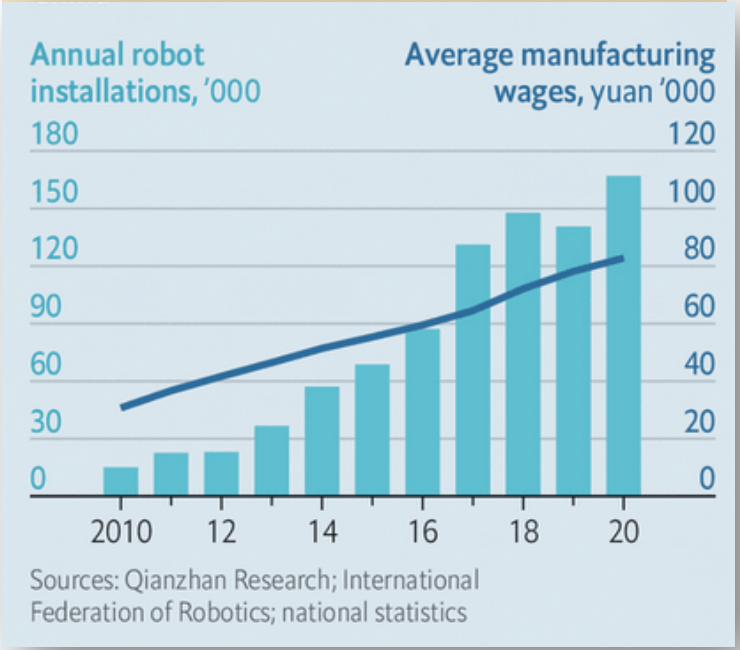

The author cited millions of skilled Chinese workers earning relatively low wages. That’s largely correct. Back in 2015, the average worker in China’s automotive sector made just 20% of his counterpart in a German plant. Since then, manufacturing wages in China has increased by more than half, but are still a far cry from European or US levels.

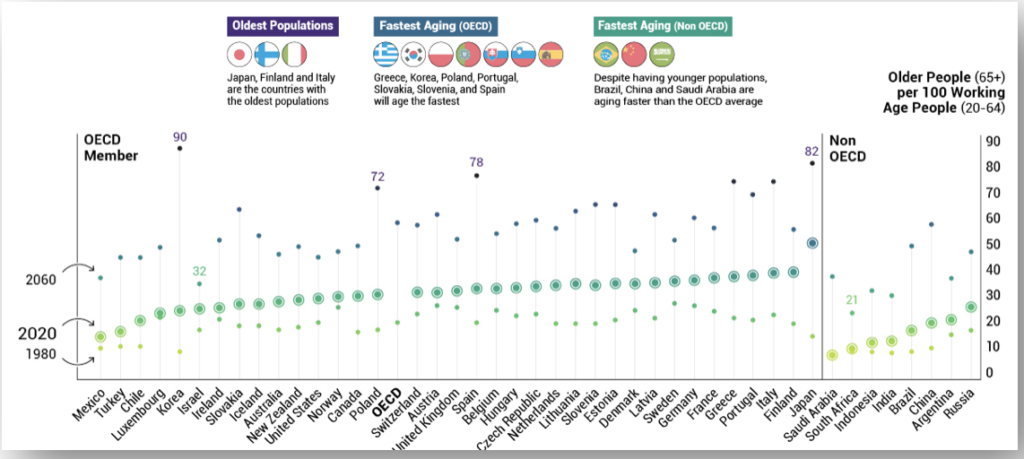

A more significant impact than manufacturing wage increases will come from China’s fast-ageing population, which in turn will adversely impact productivity unless that effect can be compensated by robotisation as outlined in the graph above.

The other arguments made by Professor Stacey relate to China’s excellent transport links and deep component supply chains.

Transport links, while a crucial part of any export-oriented economy, are only as good as the underlying manufacturing prowess and competitive advantage. With price cited as a major advantage and considering the fragility of that argument, efficient transport links in and of itself won’t be sufficient to compete.

The other argument, of deep component supply chains, also hinges on the labour cost and efficiency argument made. With the disentanglement of supply chains in full swing driven by Covid and black swan events like the Suez blockage, rearranged global supply chains will diminish that competitive advantage.

So, what else might there be? Well, with the world decarbonising, the automotive industry is undergoing a sea change. Authorities in major Chinese cities were early adopters by moving public transports’ bus fleets off combustion engines years before mayors in major European or American cities woke up to the issue. This early action, driven by air pollution along with preferential treatment for EV-ownership, created a significant domestic EV market and allowed the creation of a domestic EV industry at scale, including battery manufacturing.

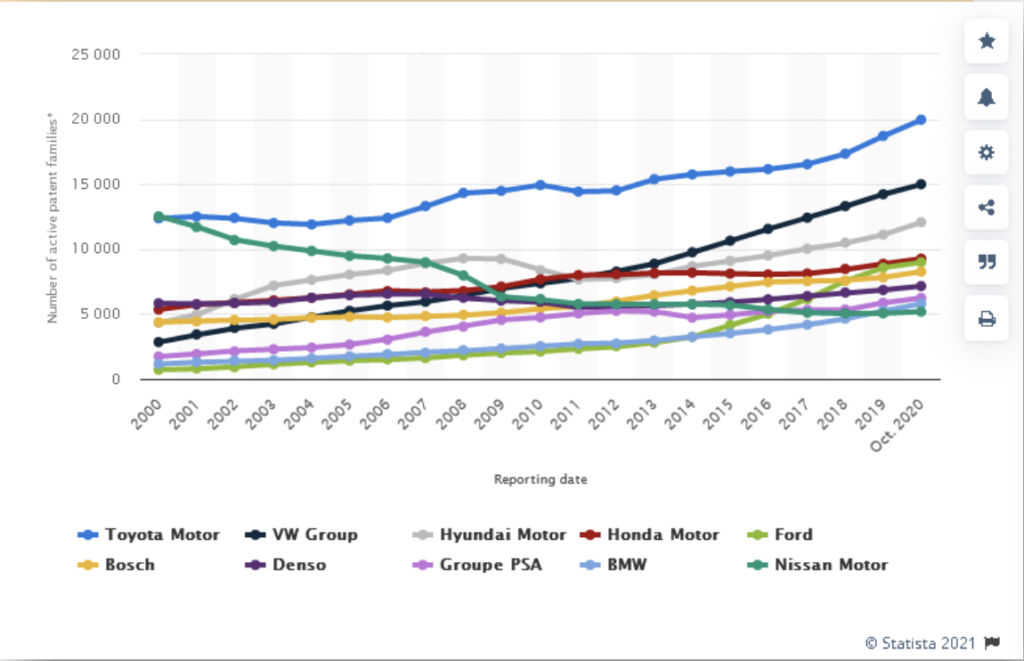

Automotive powerhouses outside of China are catching up though, which brings us to the main argument against the claim of a coming age of Chinese car market dominance: Innovation.

Largest automobile patent owners worldwide 2000 – 2020 (by number of active patent families)

Times of technological change tend to favour innovative companies. In the case of the decarbonisation of personal transportation, trends like weight reduction or energy density will be key.

Unless there will be radical changes in the global distribution of technological advancement in the car industry, Chinese manufacturers will mainly need to rely on productivity advancements and a first-mover advantage in order to generate a bigger slice of the global automotive market.

This may not necessarily result in China building the best cars in the world, but will still make the country’s car manufacturers a formidable force to be reckoned with.

And, who knows, there might even be a rephrase of Janis Joplin’s ‘Oh Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz’ on the horizon.