Amidst the clamour for local authorities to give planning permission for new homes more easily and more speedily, there is thankfully a mechanism for upholding the quality of new dwellings and their associated public realm: Design Review.

The most enlightened developers employ clever designers to unlock the potential from unpromising sites. The solutions are often innovative by necessity, setting welcome new standards in the design and construction industry. Volume house builders, by contrast, are often accused of holding back difficult sites and pushing forward with easier ones where they can apply their formulaic roll-outs. Not only does this result in cookie-cutter ‘anywhere architecture’, it also often involves loss of green. As I wrote in a previous article for Property Chronicle (‘Fields of Least Resistance’), ‘brownfield’ redevelopment sites often involve removal of previous structures, or are contaminated from previous use, which adds costs for the developer. This is why our fields are being turned to brick and tarmac (if they are not already covered in solar panels).

Local authority planning officers are increasingly under pressure, either from a pile-up of applications, lack of resource, lack of expert knowledge – or all three. Add to that the departure of in-house design officers and we are in a bad place. So, the idea of out-sourcing qualitative design assessment for large, complex or counter-policy applications has led to a relative new industry.

Design review panels already existed inside a few forward-thinking authorities and agencies in the 1990’s, but the format was introduced in a widespread way in 1999 with the formation of CABE (Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment). CABE has been regarded as a successor to The Royal Fine Art Commission, but it was born more directly out of the government’s Urban Task Force, founded in 1998 and chaired by Sir Richard Rogers. Defined as ‘The government’s advisor on architecture, urban design and public space in England’, CABE’s role was “…to influence and inspire the people making decisions about the built environment’. It championed well-designed buildings, spaces and places, ran public campaigns and provided expert advice. Initially funded by both the Departure for Culture, Media and Sport and the Department for Communities and Local Government, CABE covered a lot of interests and had sixteen Commissioners.

One of CABE’s many functions was to offer expert independent assessments of building schemes at an early stage. Its design review panel consisted of a pool of expert advisors drawn from the architectural, built environment and creative communities who reviewed schemes which had a significant impact on the local environment, or were of national importance, or which set standards for the future. CABE was known as a ‘non-statutory consultee’ in the planning process, meaning that planning departments should heed CABE’s advice when making decisions, but were not obliged to act on it. Moreover, prior to a formal planning application being made, this advice remained out of the public realm.

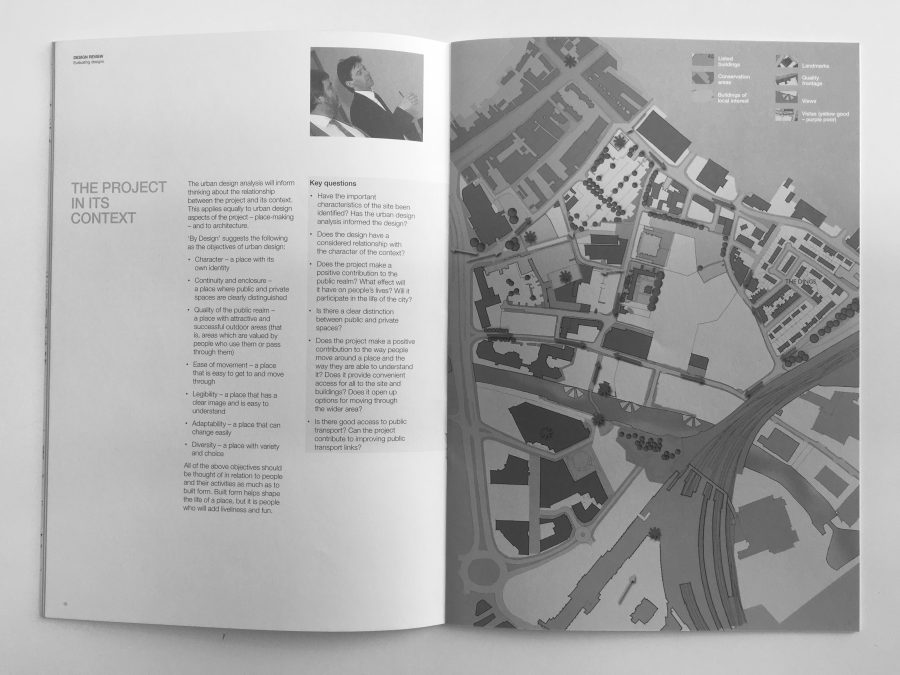

CABE was also responsible for producing many seminal illustrated publications, including one simply called ‘Design Review’ which provided guidance for both sides on how to get the best out of the process. Looking back at this booklet now, the people in the photos may have aged a bit, and there are definitely fewer ties these days, but the central message is still intact. After all, good design is good design, and as Paul Finch, then Chairman of the Design Review Committee wrote in his introduction to this booklet:

“We believe that assessing quality is to a large extent an objective process. Ultimately, of course, some questions come down to matters of individual taste and preference. It is not often, however, that questions of this kind are important in deciding whether a project, judged in the round, is a good one”.

In other words, the personal views of a panel member are usually outweighed by the process of fair critique. From my own experience, I have to agree. Whether involved in design review or even awards judging, I have found that consensus usually breaks out amongst a multi-disciplinary panel after robust discussion in an open-minded atmosphere.

Despite appointing regional representatives, one criticism of CABE was that it was London-centric. Originally located inside Richard Seifert’s seminal 1 Kemble Street in Kingsway before moving latterly and briefly to Waterloo, both headquarters were beautifully fitted out and provided a worthy home for conversations about quality environments. The perception was, however, that a scheme from anywhere in the country would be dragged to London to be critiqued by capital-living experts; not so much peer review as review by architectural peerage. So in effect it evolved from judgement by the great and the good at RFAC to a rigorously managed programme of examination with CABE. Reviewers were encouraged to act in the spirit of a ‘critical friend’ – named so since the critique was supposed to be constructive, but perhaps also due to the small world of the design industry where most project teams were being reviewed by people they knew, or at least knew of. For many architects, it was an unwelcome return to the University ‘crit’, and for practitioners like myself who sat on both sides of the review fence at different times there was sometimes a palpable sense of discomfort!

Over the course of the decade or so of CABE’s first incarnation, and in part to counter the capital-regional discourse, some of the nine Regional Development Agencies (RDA’s) evolved their own design review panels, often with the inclusion of representatives of the CABE ‘family’ – as we were called. Hence, the culture of design review was symbiotic and this has shaped the current state of affairs. Many people sitting on design review panels today are ex-CABE advisors, enablers or representatives.

CABE ran for twelve years before being dramatically downsized and some of its original functions absorbed into the Design Council in 2011.

Currently, Design Council CABE and other bodies such as ‘Design:South East’, ‘Places Matter’ (North West) and ‘South West Design Review Panel’ carry out independent design reviews in their own regions. Each panel is still advisory only and operates around a set of principles based around impartiality, expert multi-disciplinary assessment and transparency. The common denominator is that public benefits are always a key criteria.

So, what happens at a design review? Well, the ideal time for review is always as early as possible in the design process, but certainly well before the planning application is prepared. There is an early level of planning consultation called ‘Pre-App’ which is an ideal moment for review as the principles are set but not the detail. The idea is that constructive advice and comment is helpful for all aspects of design work to reach the highest standard before the detailed planning application is made.

Reviews can be expensive and more often than not the planning applicant foots the bill. For reasons of cost, it is rare for the same design review panel to continue a relationship with a particular project beyond a single review, and this is one of the frustrations of the process. Once the formal feedback report is written, panel members rarely have the opportunity to see how the design progresses unless they access the application documents themselves in the local authority planning portal.

However, I am currently involved in a review of a proposed mixed-use development of 2,500 homes with accompanying schools and commercial space, where the same five panel members have been involved in three workshop-style reviews in order to bring a degree of consistency to the review process. In a scheme of this scale, and at outline planning stage, subjects such as infrastructure planning, impact on neighbouring settlements and a robust zero carbon strategy is central to the review rather than detailed design. At this relatively early stage of the development, urban design, landscape and architectural issues are dealt with in the form of ‘design codes’ where issues of density, scale, height and material are discussed. As the scheme progresses, it should do so within these agreed parameters.

Size is not the criteria, however, and a new village extension such as this is as likely to be under review as a proposed single dwelling if it is questionable in terms of planning policy. There is whole other article sometime on the evolution of Planning Policy Statement 7 (PPS7, to Paragraph 55 and then most recently to Paragraph 79 of the National Planning Policy Framework relating to new isolated homes in the countryside.

It’s genuinely more interesting than it sounds.