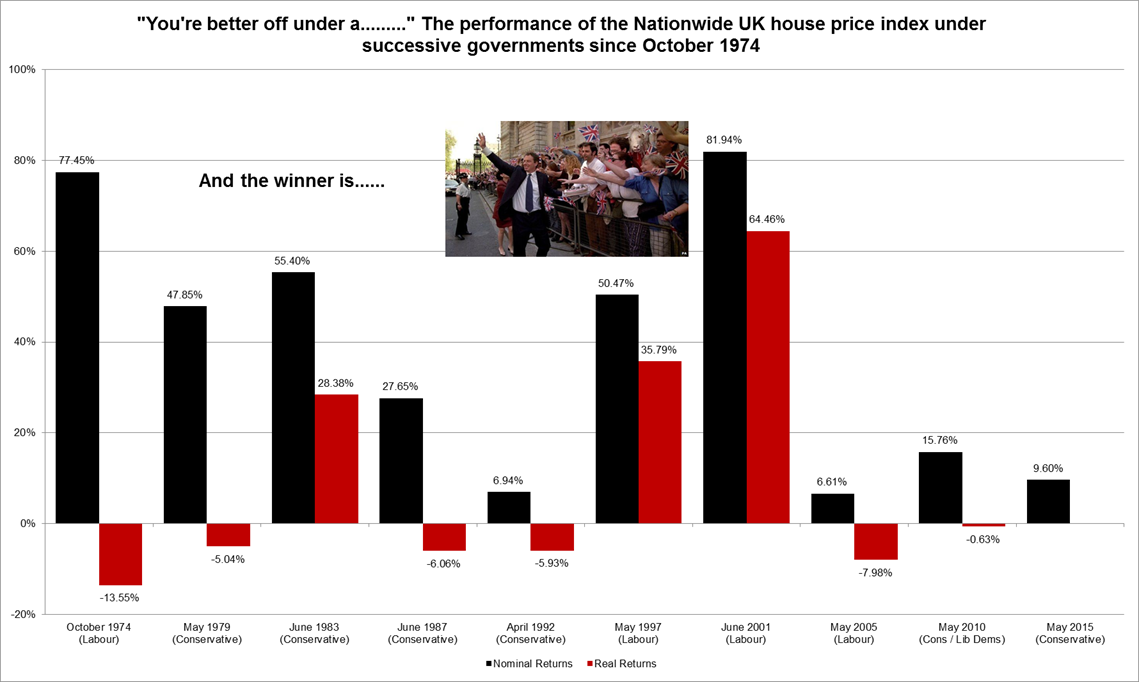

With yet another general election upon us it seems like a good time to look back and see which government has presided over the best returns for homeowners during the past forty years or so. The starting point is a good one, coming just after the Nixon administration effectively abandoned the Bretton Woods agreement, moving the west into a new economic era.

Some of you will perhaps be a little surprised by what you see on the chart above. So here are a few thoughts:

- My data points for each administration start at the end of the quarter preceding any election and run to the end of the quarter preceding the next election.

- You will note that I have also charted real returns, which is the only fair comparison, particularly as we have seen a large range of inflation over this period.

- During the Wilson/Callaghan term between October 1974 and May 1979, the Retail Price index rose by 105%; by contrast during Tony Blair’s first and second terms (which lasted eight years), Retail Prices increased by just over 22%.

- Many readers will be surprised by the fact that prices didn’t perform better during Margaret Thatcher’s tenure; but the numbers are distorted by the bear market in residential property that caught the latter part of her administration and the start of John Major’s premiership – the Nationwide UK index fell almost 17% between Q2 1989 and Q1 1992.

- In fact two years after the 1987 election the Nationwide index had risen 46% (30.5% in real terms).

- The perfect time to have purchased a property was clearly the spring of 1996, a year before ‘New Labour’ came to power. That would have coincided with the start of what Mervyn King called the NICE (non-inflationary continuous expansion) decade and delivered almost twelve years of strong returns.

But does it say anything about political parties and house prices?

Not really. Because the period in question (1974-2017) covers an era in modern post war history when a cross-party consensus was forming that home ownership was the ideal form of tenure – almost to the extent that direct social provision over this period has dried up. Remember that post war Britain was building hundreds of thousands of council houses. For example in 1968, of the 352,000 housing units completed, 183,000 (or 52%) were classed as social housing.

Margaret Thatcher started the ball rolling on home ownership by promoting the sale of council houses to their tenants (which had actually been a policy previously enacted by some Labour councils). The equation was simple. Voters in the UK predominantly like to own their home. If they can then pay as little as possible in monthly mortgage payments, and at the same time watch their single largest asset rise in value – all the better.

Governments on the other hand like to see as high a percentage of their population as possible owning a property, cementing their stake in society. It also does them no harm politically if this large pool of potential voters benefits from this ‘wealth effect’ of rising property prices – particularly prior to an election. As you can see from the chart, New Labour won two landslide elections in 2001 and 2005. Few commentators would doubt the fact that the tailwinds of rising house prices helped their cause.

Whatever you think of George Osborne, he was a very astute politician. He could see more than most that housing was a real vote winner. Which is no doubt why, rightly or wrongly, he introduced Help to Buy and cut stamp duty at the bottom end of the market. He even introduced a special ISA to help savers put money aside for a deposit. The fact that house prices were starting to pick up across the UK ahead of the 2015 election was no bad thing for the Tories – they did, after all, win.

Are changes afoot?

However, juggling all of this has not been easy, which brings us to the current state of affairs. Home ownership levels have dropped. In 2003 owner occupation rates in England almost touched 71%; figures for 2015-16 show that the number now stands below 63%. At the same time affordability levels in some parts of the country has reached saturation point.

The question we now need to address is: is the wind starting to blow in a different direction? Significantly a Tory housing minister (yes, a Tory housing minister) said in September 2016 that the government would ‘not focus on one single tenure’, and last month the Conservatives tried to make a song and dance about social provision at their manifesto launch, before being caught out over budgeting. But the point is that votes now appear to be won through promoting social provision; and if this sentiment becomes entrenched across the political spectrum, we might well ask if this means that these charts will look different twenty years from now?

What I would like to highlight, however, is that evidence still suggests that people overwhelmingly desire to own their own property; and ignoring this counter measure might create problems for politicians. Will Generation Rent really accept politicians telling them from the comfort of their ‘owned home’ that long term renting is the way forward? On top of that can people really afford to pay the levels of private sector rents in retirement? Wasn’t the beauty of owning a home that you could take out a mortgage, pay it off during your working life and sit back in retirement comforted that you have no further money to pay out? Food for thought.