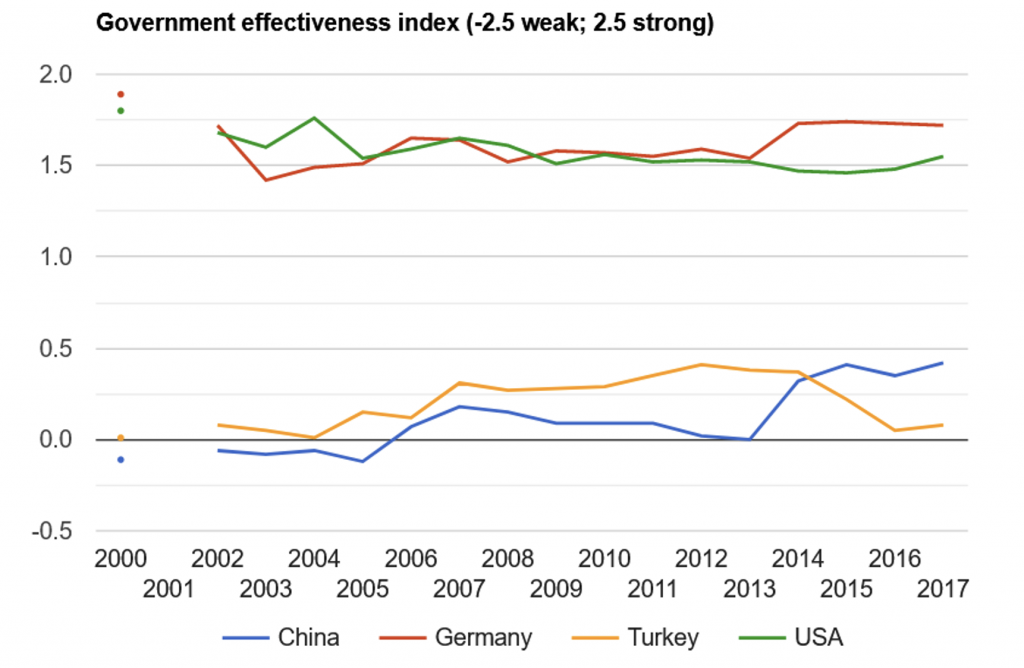

With its resurrection following the Second World War and the unification of East and West, Germany has had a remarkable journey over the past 75 years. In particular its stable and reliable public service has been a model for others. This has been reflected in consistently high marks when it comes to government effectiveness perceptions as measured by the World Bank.

This index captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the civil service including the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies.

So, how close are perception and reality?

Perception is mostly driven by individual experiences. Driving a well-crafted Audi on a long journey, it sometimes pays to look under the hood to see whether Vorsprung durch Technik is all there is.

Well, just as with those small electronic gadgets used by Audi to ‘manage’ emission levels, it pays to take a closer look at the planning and execution of major public works projects in Germany in order to validate (or refute) the government effectiveness claim above.

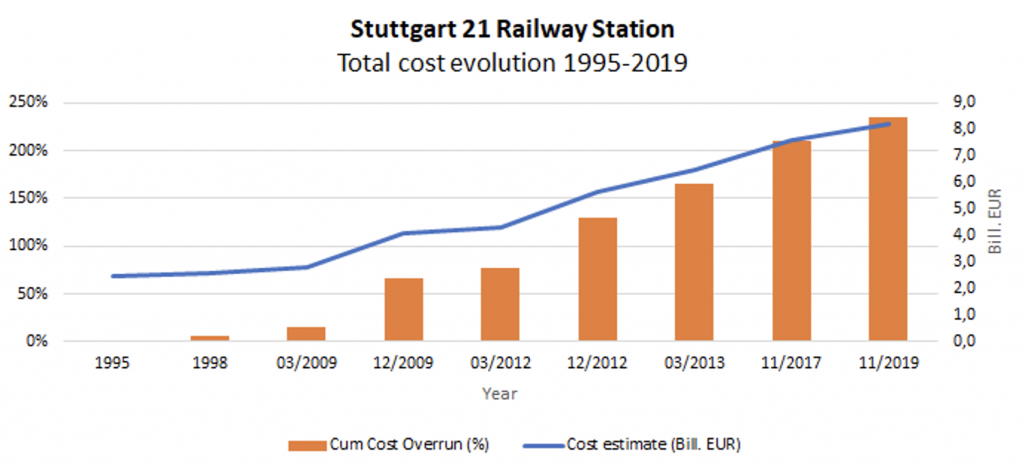

Let’s start with a project called Stuttgart 21 (S21), a major railway reconstruction project in and around Stuttgart, Germany’s key automotive center. S21 was conceived in the early 1990s, with construction starting in 2010. Initially scheduled to be operational by 2019, it is now delayed until at least 2025 with a project budget ballooning from an initial €2.5bn in 1995 to a €8.2bn ‘guesstimate’ in late 2019. Some government watchdogs consider total costs of up to €10bn, four times the initial estimate, as rather likely.

Another major infrastructure project that won’t make it into the German Efficiency Hall of Fame is the Berlin-Brandenburg International (BBI) Airport, with a design capacity of 46 million passengers a year. On the drawing board shortly after reunification in 1990, it evolved into a major national embarrassment.

Starting at a modest €800m budget, the BBI chiefs made rapid progress. After mediocre milestones of exceeding the budget by a paltry €2bn during the first 15 years of the project, they must have read the Financial Times’ “How to Spend It” column shortly thereafter. Between 2010 and 2020, costs more than doubled from €2.8bn to almost €6bn. While S21 won the race of accumulating the largest absolute cost overruns, BBI’s record-smashing 648% relative excess as well as a completion delay of 13 years and the inception-to-finish timeline of (deep breath) 30 years will be hard to beat.

How does Germany stack up against apparently lower-ranking countries?

As outlined above, China’s government effectiveness is ranked significantly lower than Germany’s. However, compared with BBI, it took the country only about one-third of the time to complete Beijing Daxing International Airport (PKX), the second largest in the capital city. Completed in late 2019, 11 years post inception, it is projected to operate at a capacity of 75 million passengers. Although it has been completed in a significantly shorter timespan than BBI, at a total cost of around €10.2bn, its per-passenger construction costs of €136 were actually even a tad higher than those of BBI at €130.

Another interesting reference point is the new Istanbul Airport. Despite Turkey’s extremely low World Bank government effectiveness perception, the project’s timeline execution has been exemplary. Phase one of the project with a capacity of 90 million passengers was completed in June 2020 after roughly five-and-a-half years of construction and about nine years since inception. With budgeted total construction costs of €22.15bn for all four phases to be completed by 2025 and accommodating 200 million passengers, per-passenger construction costs will amount to around €111.

Is Germany actually failing at major public works?

The long and short answer is: it depends. Looking at the three airport projects, it appears that in terms of a pure cost-per-passenger comparison, Germany, despite being a high-cost, heavily regulated environment, comes out at par.

However, in terms of executing projects within a reliable time and cost framework, the country has significant shortfalls.

Looking at both, S21 and BBI, unnecessarily complex planning processes, a lack of competent management and oversight and political meddling with significant ‘white elephant’ potential are the main culprits. Tender mechanism (where the cheapest one wins) prone to exploitation by rogue players, as in the case of BBI, and a lack of digitalised planning, tracking and execution systems to create transparency, set these projects up for failure.

The speed at which countries like China and Turkey get major public works done comes at a significant cost, including major health and safety shortfalls resulting in construction site injuries and deaths. However, in order to compete on the world stage, Germany needs to get much better in completing public works at home. Dirty deeds don’t always come cheap – some just need to get done… on time.