Predictions for prolonged British misery are based on fears of a no-deal Brexit and a pandemic second spike – but both risks carry little economic downside.

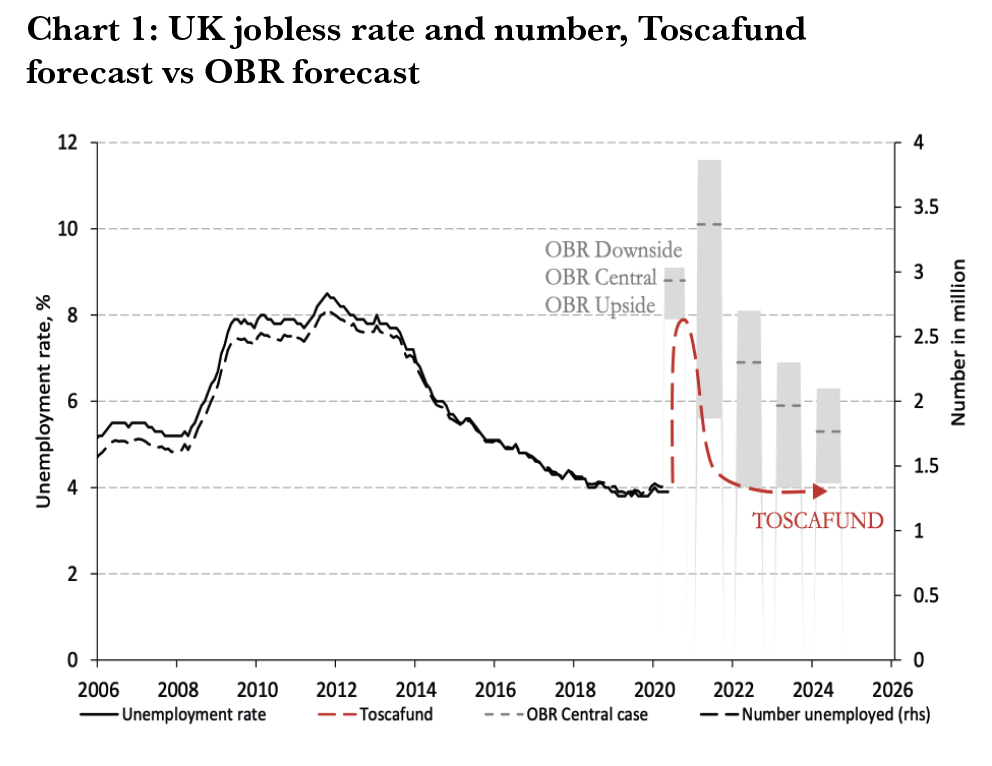

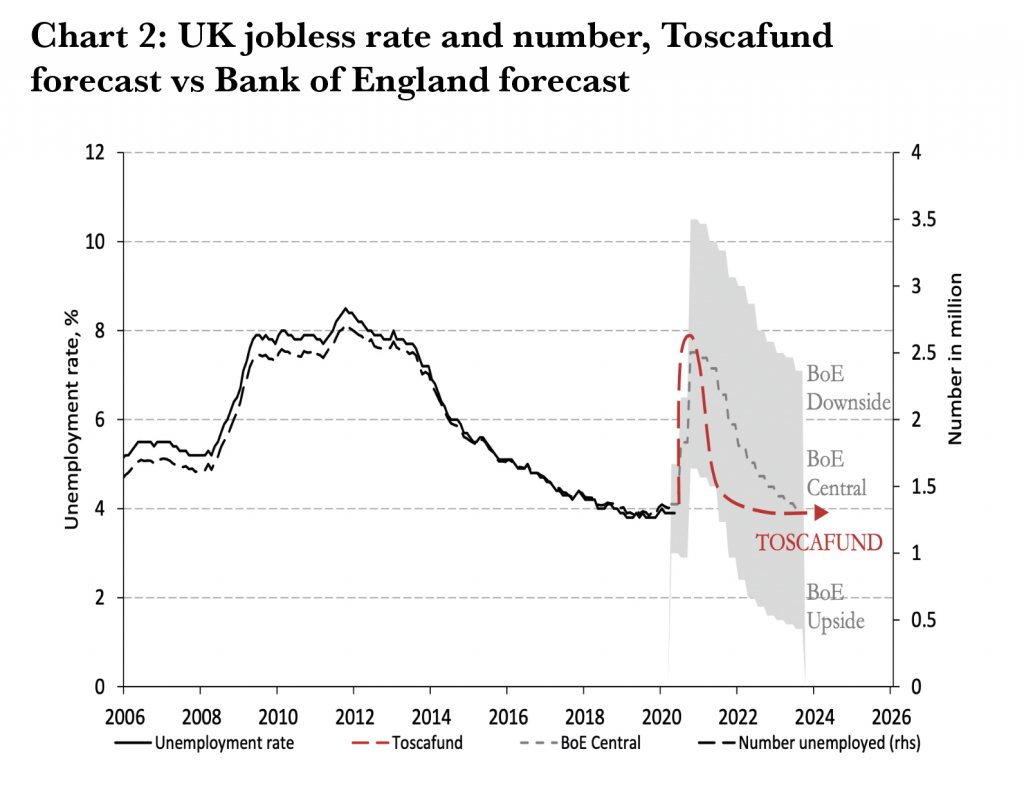

When any economy suffers significant job loss, three things need to follow to avoid long-term economic impairment. It is not sufficient merely to see the quick creation of new jobs to replace those lost; these jobs must also be at least as generous in their rewards to workers and as high in productivity as those they replace. With this triple jeopardy in mind, let me consider the future of the UK labour market, and in turn the property sector and the wider UK economy. Yes, the UK has been hit by a significant jobs shock, but not the first it has faced in my lifetime. Where it is exceptional is in being the first time that swathes of UK sectors have done rather well from the same shock that has so seriously hurt others.

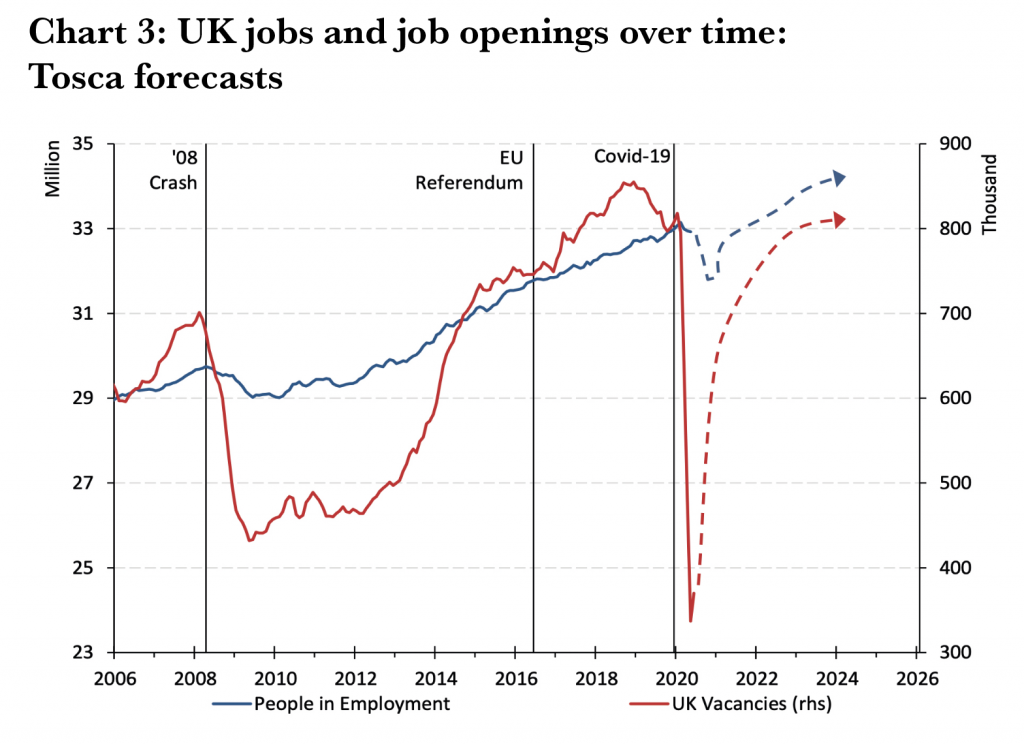

Of those sectors badly affected, few can claim they offered generous financial rewards to the vast majority of their former workers. Indeed, the low rewards derived from the fact that those roles were very often undemanding in the skills required. The workers I write of are those in ‘go to’ retail and leisure venues or in travel-related jobs (tour operator and airport staff), laid off because we have been locked in, locked out and grounded. Crucially, the skills of those among them – from shop or kitchen floor to management – whose old company has now gone out of business are perfectly transferable across to the public sector as well as to e-commerce or to those parts of the leisure and tourism market capitalising on a surge in staycationing.

Many of the firms that suffered a hard close will reopen again and do so with the need to rehire. As for those all-too-numerous businesses sadly forced to close permanently, be in no doubt that with landlords competitively seeking new occupiers, labour keenly looking for work, and capital more liquid than post any recession, new firms will start up in considerable number and scope. Moreover, these firms will demand labour with skills that are, for the most part, not greatly different from those possessed by the newly displaced workers.

Britons being forced to stay in the UK because of a weakened pound and/or more disruptions to their movement is a net economic positive to the UK

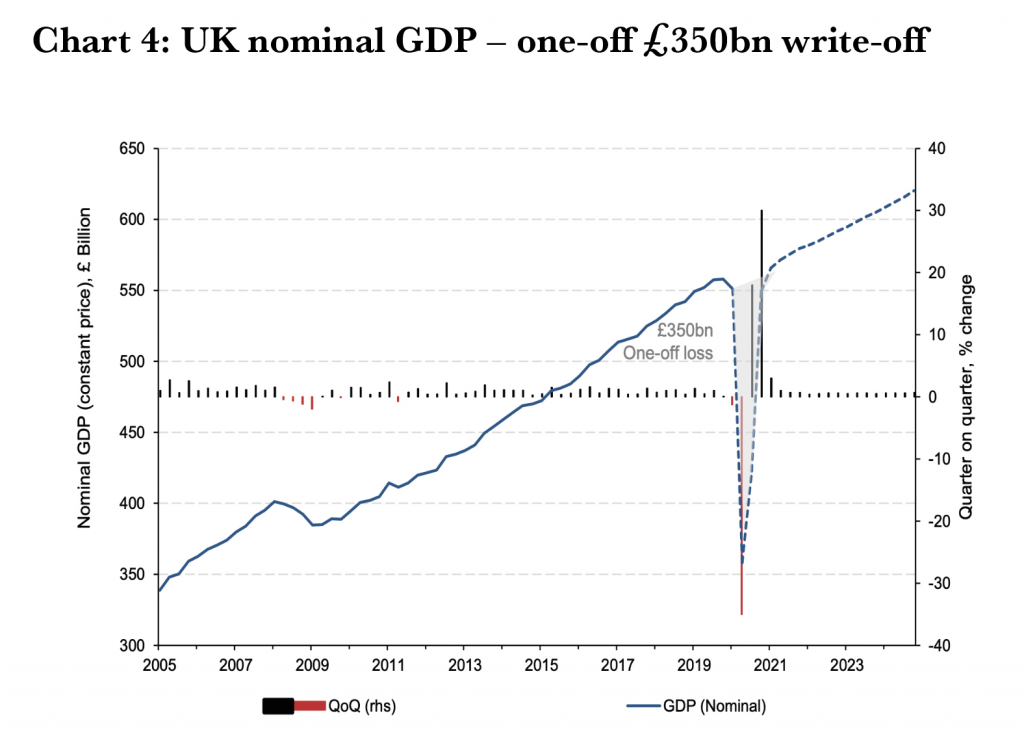

There will be those who challenge my claim that the UK will return to economic normality sooner than the consensus predicts. Atop their list of reasons for cynicism will sit two standouts. One of these is the possibility of a cliff-edge Brexit; the other is the prospect of a second spike in covid infections. Let me defend my forecasts not by denying these possibilities but by following them through.

Imagine the UK and the EU failed to come to amicable agreement. In this case, it is inevitable that the pound would weaken materially against the euro; parity would not surprise me. The resulting competitive boost to the UK would hardly be unwelcome. As for the inflation in the UK that would result from a no-deal Brexit, remember that the biggest challenge facing central banks across the developed world is actually the threat of deflation. Another consequence of no-deal would be to create frictions for travellers that we have not faced before, prompting more of us to vacation at home, bringing benefits for our homegrown tourism industry.

As for a second spike in infections, this is a real and present danger everywhere, not least across the eurozone. Recurring spikes further disrupt travel across national borders, and here the UK is actually an economic beneficiary, given that it has long run a trade deficit in travel and tourism. The greater the travel disruption, the more of the money that once travelled out of the UK stays and circulates for our economic good. Furthermore, in the event of more spikes e-commerce and e-finance would continue to enjoy job creation. In short, Britons being forced to stay in the UK because of a weakened pound and/or more disruptions to their movement is a net economic positive to the UK and net loss overseas.

Let me continue with the theme of human movement but switch from travel for leisure to travel for work. As August makes way for September and we move towards January 2021, when the Brexit transition period ends, each passing day is sure to see more Europeans who once worked here, but have since returned home, furtively fill in the forms to ensure they have the right to return to work in the UK when it leaves the single labour market.

I have long predicted a last-minute Brexit deal giving EU nationals the most lenient possible working visa terms. But let’s assume I am wrong. As I said above, in the event of a no-deal exit the pound will weaken against the euro, and trade and travel will suffer new frictions. Both sides are certain to see economic fallout, but it will fall worse on the likes of Spain, Greece, Cyprus and the many others across the EU for which Britain is a significant source of income. Overlay the continued harm done to important tourism sectors if we see ongoing spikes here and across the EU, with resulting travel disruptions, and one has a recipe for such economic pain across continental Europe that ever more prime-age adults will make visa arrangements to migrate for their betterment. And while Australia and Canada will rank highly in their ambitions, so too, I am convinced, will the UK – a conviction born of what we have seen in the last decade or so.

To repeat, then, a no-deal Brexit and further covid infection spikes would combine to increase interest among EU nationals in moving to the UK. Rather than see such arrivals as further competition for what work there will be in 2021 and beyond, please see them for what they are sure to be: creators of demand, not least for homes, and forces for our economic good. The point I cannot stress enough is that in these uncertain times, one certainty is that the EU and the eurozone within it face challenges like never before.

To summarise: yes, certain UK sectors will never recover their headcounts, but others will go on a recruitment drive. And the new jobs being created are unlikely to reward workers any less than do the ones lost, nor will they require skills that those without work do not possess or cannot quickly acquire. The reality is that while it would be naive to claim the unemployment we face will be merely frictional, it is reasonable to argue it will not become ingrained or long-term, as defined by those without work for over a year. We last suffered long-term unemployment in the 1980s because of mismatches that, thankfully, we do not suffer today.

Article provided by Macrobond.