In mid-April 2021, President Biden declared an imminent and rapid withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan based upon a timeline handed down from the previous administration. Not surprisingly, this announcement prompted advances by the Taliban, a religious-based insurgent group that had previously ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 when the US ousted them from power and installed a secular regime.

In early July, despite aggressive advances by the Taliban, Biden doubled down on his decision to hasten and complete the withdrawal of troops by the end of summer. National Public Radio quoted the president speaking optimistically that the current regime would hold. “Do I trust the Taliban? No,” Biden said. “But I trust the capacity of the Afghan military, who is better trained, better equipped, and more and more competent in terms of conducting war.”

Within six weeks, the capital city of Kabul had fallen under the control of the Taliban. President Ashraf Ghani fled the country with cars and cash, other individuals connected with the former government sought asylum, and US diplomats and other personnel were evacuated in a scene eerily reminiscent of the rapid fall of Saigon four decades earlier.

The “better trained, better equipped,” and “more competent” Afghani regular army appears not to be any of those things.

How could a ragtag group of religious fundamentalists – organised by seminary students and with little formal military training – grow to be so effective in controlling a territory that has resisted rule by some of the most formidable world powers, including the British, the Soviets and (most recently) the United States? And why did the preexisting Afghan government crumble so quickly?

Interestingly enough, an answer to these questions can be found in a quirky little academic field known as the political economy of religion.

An economics of religion

Whenever I tell non-academics that my career has centered on the economic study of religion, they generally think I’m investigating how megachurches make a lot of money. Alas, no.

The economic study of religion, with roots in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (Book V), was pioneered by sociologists Rodney Stark and Roger Finke, and economist Laurence Iannaccone in the mid-1980s. Their primary insight at the time was to challenge the reigning theory of secularisation that proposed the increasing irrelevance of religion over time. Using the most basic concepts from economics (eg, marginal utility, trade-offs, incentive-based behaviour), they argued that declining religious participation was not a function of declining demand as much as it was a matter of over-regulated supply.

This perspective gained significant attention when it was realised that declining religious population was largely restricted to Europe (where secularisation theorists focused their attention) and that the rest of the world was vibrantly religious and even experiencing fundamentalist revivals (even in the most oppressive of atheistic states such as China). In the early 1990s, a couple of political scientists – myself and Carolyn Warner – began directing attention to the role that government played in crafting the economic incentives of religious actors.

Strict churches are vibrant

One of the most important and pathbreaking findings to come from the economics of religion can be attributed to Laurence Iannaccone in the early 1990s and it was an insight that bears directly on the success of the Taliban: groups with strict behavioral rituals are very effective at organising collective action.

Iannaccone was perplexed by the organisational vibrancy of some of the strictest churches in the United States, such as Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses and Orthodox Jews. These confessions, oddly enough, had some of the costliest behavioural codes while also having memberships that were intensely devoted and highly active.

This was a puzzling observation, since standard economic theory would assert that the costlier a group is, the less likely people would join. Organisations that impose high costs on members should lose members to lower-cost groups. Interestingly, these strict churches held their own and a number of them were actually growing (eg, Mormons) whereas mainline denominations such as the Episcopalians and Unitarians were losing members rapidly.

Iannaccone’s answer was simple and brilliant: strict behavioural codes (eg, no drinking, refuse blood transfusions) and stigmatising behaviour (eg, wear distinctive clothes) weed out free riders in groups and enhance cooperation. Religious denominations are essentially good clubs, wherein members share in many collective benefits (eg, welfare provision, fellowship). The quality of those collective benefits is a function of how many people actively contribute. If everyone chips in, the organisation is vibrant. However, if many members are there just to receive those benefits, but do not participate (ie, free riders), the quality of the good is dissipated and the organisation becomes anemic.

To limit free riding, strict religious groups require members to prove their loyalty by engaging in costly and visible behaviour that no lazy individual would want to bear. Mormons require two-year missions of their young adults, not to win converts, but rather because only the most dedicated people can endure having doors slammed in their face for two years. An Orthodox Jew who keeps the Sabbath holy and maintains strict dietary habits signals their strong commitment to the group. Many other groups, such as fraternities, sororities and friends’ societies (eg, Masons) have odd and often embarrassing rituals required for entry as a means of sorting out those who are committed from those who just want club benefits without contributing.

Engaging in stigmatising behaviour also limits the outside opportunities of group members and binds them more closely to the organisation. Mormons cannot go out drinking at the bars on Friday night, so much of their socialising occurs within their congregation, which has the effect of making them more loyal to the group.

A final benefit of these costly barriers to entry is that the resulting good club is of a very high quality. Since only highly committed individuals belong to the group, everyone cooperates effectively and the resulting collective benefits are very valuable. Strict religions are costly, but considering the benefits the group provides it’s a good deal.

Strict religions enhance rebel groups

Another economist, Eli Berman, took Iannaccone’s insight and applied it to the study of terrorist organisations. In his superb book, Radical, Religious, and Violent, Berman explained that engaging in terrorist plots (eg, suicide bombings) or operating a rebel group, requires a high degree of cooperation among group members. If any one individual is captured or defects from the group, the entire organisation can be compromised. (Berman noted that suicide bombings are not typically ‘lone wolf’ operations, but involve many individuals who have different roles, such as scouting out targets, making the bomb and distracting guards.)

Linking a strict religious sect to a radical rebel group is a very effective way of enhancing loyalty and cooperation. Individuals who keep strict dietary habits, pray publicly several times a day and study religious texts to the exclusion of all other activities demonstrate to others that they are likely to be good cooperators.

While the ideology (or theology) of a group may motivate extremist political behaviour, Berman argues convincingly that it is really the strict behavioural codes that are the primary engine driving the success of these rebel groups. It should be noted that not all fundamentalist religions are violent – only a very tiny fraction of devout fundamentalists tend to be and this is linked to the organisational incentives and political context in which they operate.

The Taliban provides effective governance (relative to the alternative)

The Taliban is an excellent case example of Berman’s thesis. Its fundamentalist version of Sunni Islam imposes very strict requirements upon all members. It is easy for them to identify and choose leaders who are the most cooperative and know that they can be trusted not to defect from the organisation. They are a disciplined organisation wherein lower-level militants, officials and religious leaders are unlikely to defect from the group’s central goals, which is the creation of a unified Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

In the 1990s, this became very important in their rise to power in Afghanistan. Following the defeat of the Soviet occupation in 1989 (partly due to the USSR’s own collapsing economy), Afghanistan fell into a disorganised mess of rival ethnic clans vying for political and economic power. A disunified governing system could not effectively collect taxes and the nation’s infrastructure, including the ability to guarantee basic market interactions, fell into total disrepair, making it one of the world’s most impoverished nations.

The Taliban, however, proved to be the only unifying entity that could guarantee safe trade routes, collect taxes without excessively plundering the population and provide essential public goods to key cities. It did this initially by securing control over the Kandahar-Herat Highway that served as an important trade route between Pakistan, Iran and Turkmenistan, and was part of a larger ‘ring road’ that was the only navigable route connecting important cities within the country (see Radical, Religious, and Violent, pp 20-30).

Previously, different tribal organisations would take sections of this highway, stop all transit and tax the commercial merchants. With so many taxing organisations taking money from truckers every few miles, it became too expensive for anybody to run their goods along this road. Commerce ground to a halt. Taxes couldn’t be collected. The country’s infrastructure crumbled.

The Taliban, however, could station its militants at key locations on the highway and tax merchants only once while protecting truckers from other bandits along the route. Since devout members of the Taliban proved their loyalty via adherence to strict religious codes, they were unlikely to plunder the trucking caravans in an opportunistic fashion.

Commerce returned, the Taliban collected revenue with a tolerable level of guaranteed taxation and it used these funds for other infrastructure projects in the country. Not surprisingly, this made the Taliban reasonably popular relative to the chaotic anarchy that had previously reigned. People may not have liked their intense religious views, but at least the roads were operable and the electricity came back.

Additionally, the Taliban proved itself to be reasonably fair arbitrators of a civil justice system and religious leaders (imams) often heard cases between individual disputants arguing over various contract violations (see Berman book linked above). Ruling on contract disputes (eg, who owns some goat pasture land) may sound mundane, but such a system is vital for economic activity to occur. If people trust that contracts and property rights can be fairly enforced, they are more likely to make longer-term investments that promote economic growth. Indeed, the Taliban leadership are so trusted among the population to resolve such disputes that they continued to function as a shadow civil judiciary over the past 20 years.

Why did the Taliban succeed?

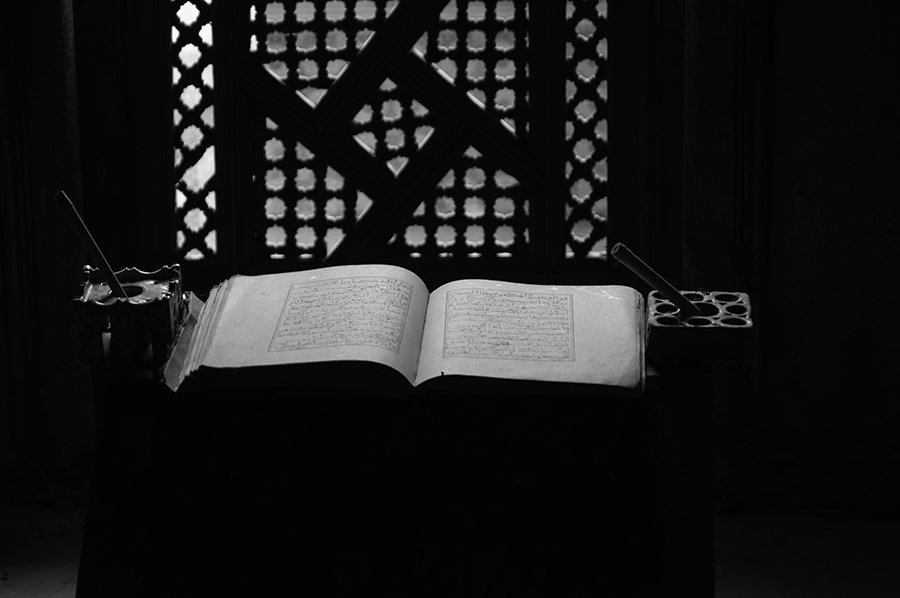

All of this was possible because the Taliban is rooted in a strict religious movement where leadership and other key members must prove their loyalty by adhering to strict behavioural requirements (eg, prayers, study of the Koran, strict dress codes). The previous secular government did not have this advantage. Their leadership was rife with corruption and it was nearly impossible for the central government to control local officials, who preyed on their local populations with excessive taxation and demands of bribes for services. When the Taliban rolled into a town, it was not surprising that the local population put up little resistance.

Many of the extreme religious codes that the Taliban impose on the population writ large may not be universally popular, although it is difficult to take opinion surveys in this environment. Nonetheless, it is not a long stretch to think that the strict and predictable implementation of Sharia law is preferable to the arbitrary, despotic rule that Afghanis has had over the past two decades.

None of this is meant to diminish the difficulties still facing Afghanistan. I am not an apologist for the incoming Taliban regime and it is well-nigh impossible that it will institute a classically liberal government with broad-based civil rights that I ideally prefer. Rather, I only offer an explanation for why the Taliban has been able to overrun the country in short order: it represents a disciplined and tolerably trustworthy governing option relative to the corrupt regime that only existed with the help of US troops guaranteeing their power. The future remains uncertain for Afghanis, but the Taliban may be delivering social scientists important lessons in how rebel groups win power, how effective governance may displace corrupt regimes and why religion still remains important in the 21st century.

Originally published by the American Institute for Economic Research and reprinted here with permission.