In both the world wars, Britain was allied with France and Russia against Germany. Yet this pattern was of relatively recent origin and it represented a reversal of that which had existed until the beginning of the 20th century. For most of the 19th century, and earlier, Germany had usually been Britain’s ally whereas her most consistent enemies were France and Russia. The key years for this fundamental realignment of British foreign policy were 1904-7, the period which saw the Entente Cordiale with France in 1904 and the Convention with Russia in 1907. In promoting and cementing these alliances, the personal diplomacy of Edward VII, the ‘Uncle of Europe’, played a role that was both significant and helpful.

Britain’s enmities with France and Russia and her friendship with Germany – and, before German unification, Prussia – were of long-standing. In the wars against Louis XIV and later Napoleon, Britain generally co-operated with Prussia against the might of France. In the Crimean War of 1854-6, Britain even found herself in temporary alliance with France against Russia. That war reflected the long-standing British animus against Russia, and this remained evident at the Congress of Berlin in 1878. It was still apparent in the Anglo-Japanese alliance of 1902 and during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5 Britain’s sympathies were firmly with Japan. Rather than France or Russia, until the end of the nineteenth century, it was Germany that Britain – with its royal family of German descent – regarded as a natural ally.

“Tensions were growing between Britain and the rapidly rising new power in Europe, Germany”

By the opening years of the 20th century, however, these traditional alignments were beginning to change. Tensions were growing between Britain and the rapidly rising new power in Europe, Germany. There was considerable criticism of Britain in Germany during the Boer War (1899-1902) and by this time Germany was also building up an Imperial Navy to rival that of Britain. The German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, had a love-hate relationship with Britain, and he distrusted Edward VII, his ‘Uncle Bertie’. Later, Wilhelm even claimed in his memoirs that, “…my uncle was working for the policy of encirclement for the annihilation of Germany”. The Kaiser’s fears may have been disproportionate, but they were not utterly irrational. Edward disliked his nephew and was willing to contribute to his diplomatic isolation.

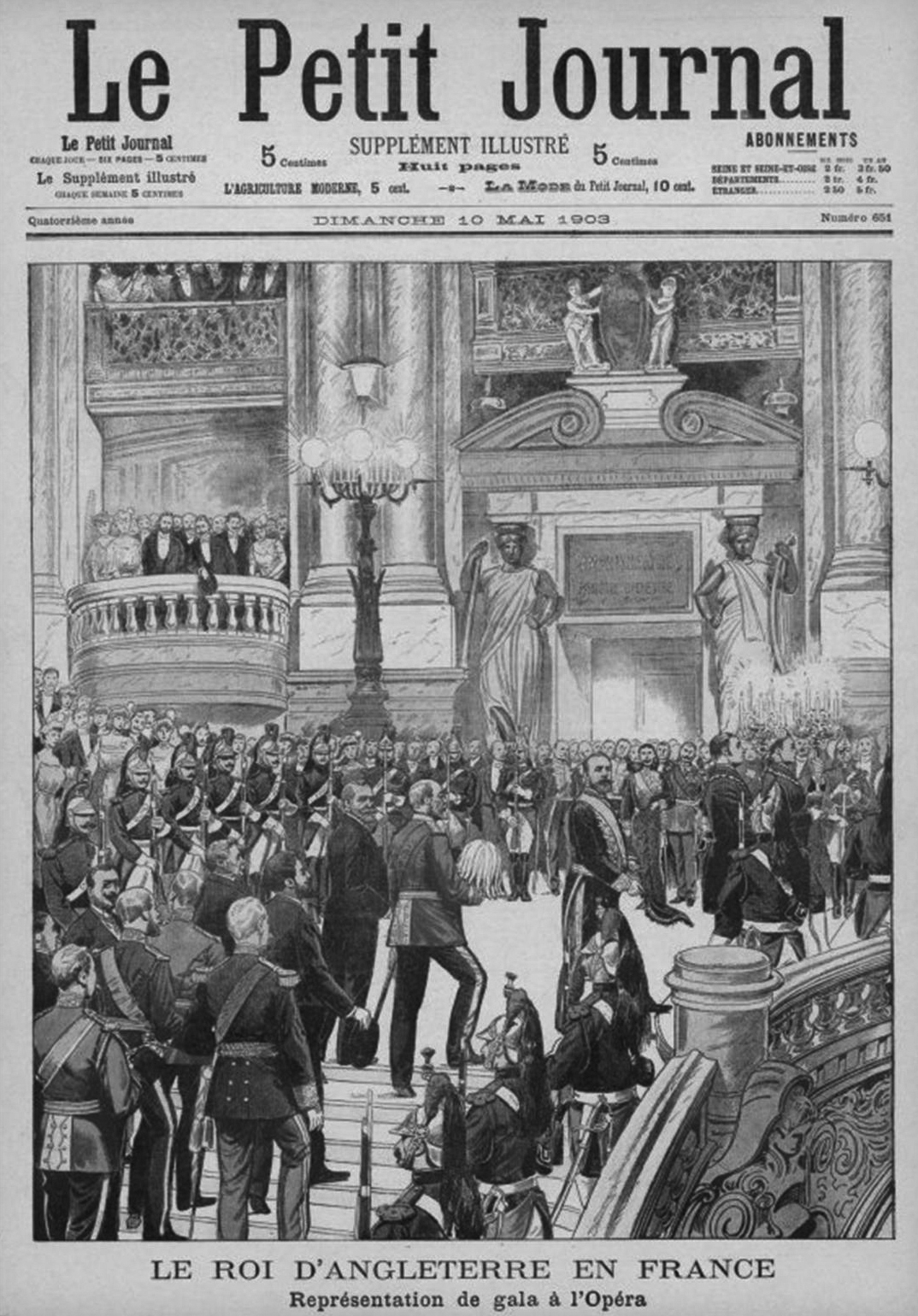

An important moment in this process came in May 1903 when Edward made a state visit to Paris. His initial reception was a little cool – some spectators chanted “Vivent les Boers!” – but Edward’s natural charm soon won him immense popularity. The crowds particularly appreciated his frequent impromptu speeches in French, and dubbed him ‘le roi charmeur’. He had visited France frequently while Prince of Wales, and his knowledge of French culture – not to mention French food and wine – was greatly appreciated. His visit proved a huge success and helped to create an atmosphere of Franco-British goodwill that was crucial in smoothing the way towards the Entente Cordiale of April 1904.

Russia proved a slightly harder nut to crack. The historic antipathy between Britain and the ‘Great Bear’ was not helped by the Dogger Bank Incident of October 1904 when Russian battleships accidentally fired on British trawlers in the North Sea after mistaking them for Japanese vessels. There was also considerable British disapproval of the suppression of an abortive revolution in St Petersburg on ‘Bloody Sunday’ in January 1905. Nevertheless, spurred on partly by mutual fears of the rise of Germany, Britain and Russia were able to agree a Convention in August 1907 which marked a significant thaw in the long-standing imperial rivalry between the two powers.

This time, unlike with the Entente Cordiale, Edward’s visit followed the diplomatic rapprochement rather than preceding it. His visit to the Tsar and his family at Reval in June 1908 was nevertheless important in cementing relations between the two countries. He was ‘Uncle Bertie’ to Tsar Nicholas II as well and the mutual affection between the two contrasted with Edward’s more difficult relationship with Wilhelm II. Edward’s personal diplomacy with the Tsar in 1908 helped to reinforce what the diplomats had achieved the previous year. Lord Hardinge, who had been Ambassador to Russia and then Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, later recalled that, “there was no disguising the fact that the Tsar and Tsarina were extraordinarily happy in the company of their uncle and aunt, and the visit had largely a family character”.

“the Tsar’s visit was carefully stage managed, and he and his family spent the whole time at Cowes on the Isle of Wight in order to avoid the hazard of hostile demonstrations”

These Russo-British ties were further strengthened the following year, when the Tsar and his family paid a return state visit to Britain in August 1909. This visit provoked some consternation, particularly among Labour MPs and trade union leaders, who protested at the Tsarist regime’s treatment of Russian workers. For this reason, the Tsar’s visit was carefully stage managed, and he and his family spent the whole time at Cowes on the Isle of Wight in order to avoid the hazard of hostile demonstrations. This plan, which Edward VII had encouraged, paid off admirably and the visit proved a great success. As he prepared to leave, the Tsar issued a statement that it was, “his firm desire and belief that this all too brief visit can only bear the happiest of fruit in promoting the friendliest feelings between the governments and people of the two countries”. Those friendly feelings were to be crucial five years later, when the two countries fought as allies against Germany. Once again, Edward VII’s personal diplomacy had helped to reinforce the relationships that his ministers were seeking to build.

The realignment of British foreign policy during these years was thus a decisive moment in the development of 20th-century international relations. The pattern of alliances that was to be such a marked feature of the two world wars was set in place. Edward VII made an important personal contribution to this process, while Wilhelm II saw Britain increasingly aligned with France and Russia rather than with his own country. Given the long-standing friendship that had existed between Britain and Germany, and the fact that he was himself the product of an Anglo-German marriage, it is perhaps not surprising that the Kaiser saw this British realignment as a personal rejection.