Government policies and elections affect house prices, but in what way and by how much? A new report from Birmingham City University researchers reveals why property professionals should take note when elections are in the air

The period of time before an election can mean instability in political terms. Who will win the election and will policies change dramatically depending on who does.

For professionals working in the property market, as well as property owners and buyers, it would seem logical to assume that the political instability before an election would lead to lower prices in the housing market. Conversely, post election – once the continuing or new government is safely installed in office and policies are clear and hopefully more stable – it would seem safe to assume that house prices would begin to rise again.

Yet in reality this is not necessarily the case. Using the Nationwide UK housing market data, research by Birmingham City University (BCU) shows that these assumptions prove not to be true.

Report* authors, Professor David Higgins, Dr Timothy Lee and Bismark Aha (PHD student) from BCU School of Computing, Engineering and Built Environment, utilised 60 years of quarterly UK house price data to examine the relationship between the movement in real house prices one year before and after government elections.

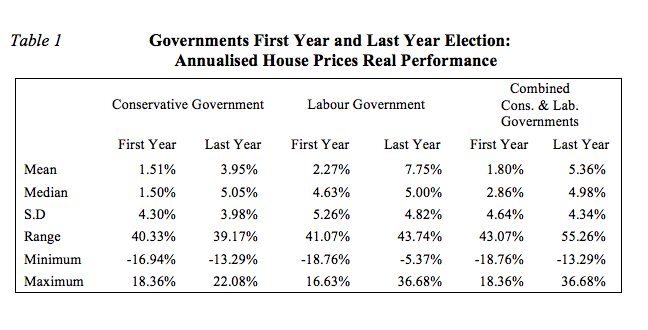

They found that the key variation in house price movement is at election time. House prices performance is significantly better the year before an election compared to one year post election.

On average over the past four decades, one year before an election the annualised quarterly real house price increased by 5.36 per cent, this compares to one year post election, when prices increased 1.80 per cent.

Over the last 60 years, quarterly real (inflation removed) house prices increased by an annualised return of 3.25 per cent. There appears to be nominal variance in house price movement between the elected Labour and Conservative parties.

As revealing as this research is, what do the findings mean for the property market or the house buyer or investor, other than putting prices up in an election year and then down again slightly the year following an election?

Ultimately, house owners which represent approximately 63% of the property market, form a large and important voter base and it is enlightening to realise how much government policies, can affect the state of the housing market at both non-election and election times.

The Authors argue that housing is more than a unique and valuable asset; in fact, it is a key component of wellbeing in society generally. Not only does housing provide essential shelter for a country’s population, it is also a source of key economic activity for the country.

As an important part of a country’s prosperity, controlling the various aspects of housing is clearly a core long-term government mandate. Consequently, the type and timing of policies across various levels of government – local, regional and central – can have far reaching effects on house prices.

Government policies affect all aspects of housing including the space market (demand), the property market (property market conditions and supply) and the capital market (finance).

Demand in the housing market is affected by government policies that include population policies – such as overseas migration, policies for first time home buyers and any incentives offered, and policies on opportunities for overseas owners to purchase residential properties.

In the capital market, Government policies that affect finance include monetary policies, changes in property taxes including transaction tax – stamp duty and any regulations that impact on alternative asset classes, and changes to pension/superannuation policies.

In the area of property market conditions and housing supply, Government policies can affect the release or rezoning of new residential land, any changes in planning policies such a change to housing density, and building regulations such as a new sustainability agenda.

As with all these Government housing policies, the timing of these policies and the policy implementation can be used to manage and stimulate the housing market. The impact of these policies on house prices could be gradual or immediate.

As already stated, home owners represent a large percentage of the voter base and, as such, policies that a Government implements close to an election may influence their voting intentions. For example, if a Government announced the scrapping of stamp duty this could affect the way investors voted dramatically.

Many house price drivers are linked to macroeconomic policies, which are made within a political framework. Consequently, in this environment, although housing outcomes are difficult to validate they can be an important election vote winner, as home owners represent a large and stable voter base.

In recognising policy makers’ active management of house prices for political gain, the short-term benefits of appealing to a large number of voters may conceal underlying long term flaws in the residential property market. Leaving these issues unaddressed could be more complex than often perceived.

This Birmingham City University research clearly identifies major variations in house price performance around election time and, consequently, when it comes to making residential property decisions both buyers and sellers need to be aware of these issues and to take into account where Governments are on the election cycle.

Ultimately, perhaps the property market and politics are much more closely linked than has been perceived. Property buyers and sellers need to be cautious around the political cycle and forthcoming elections and make sure that they read the election promises small print carefully.

(( + relevant graphs and tables etc.))

* BCU research report: “UK Political Cycle and the Effect on National House Prices: An Exploratory Study” by Professor David Higgins,