How they work and the implications.

Part 1: the economics

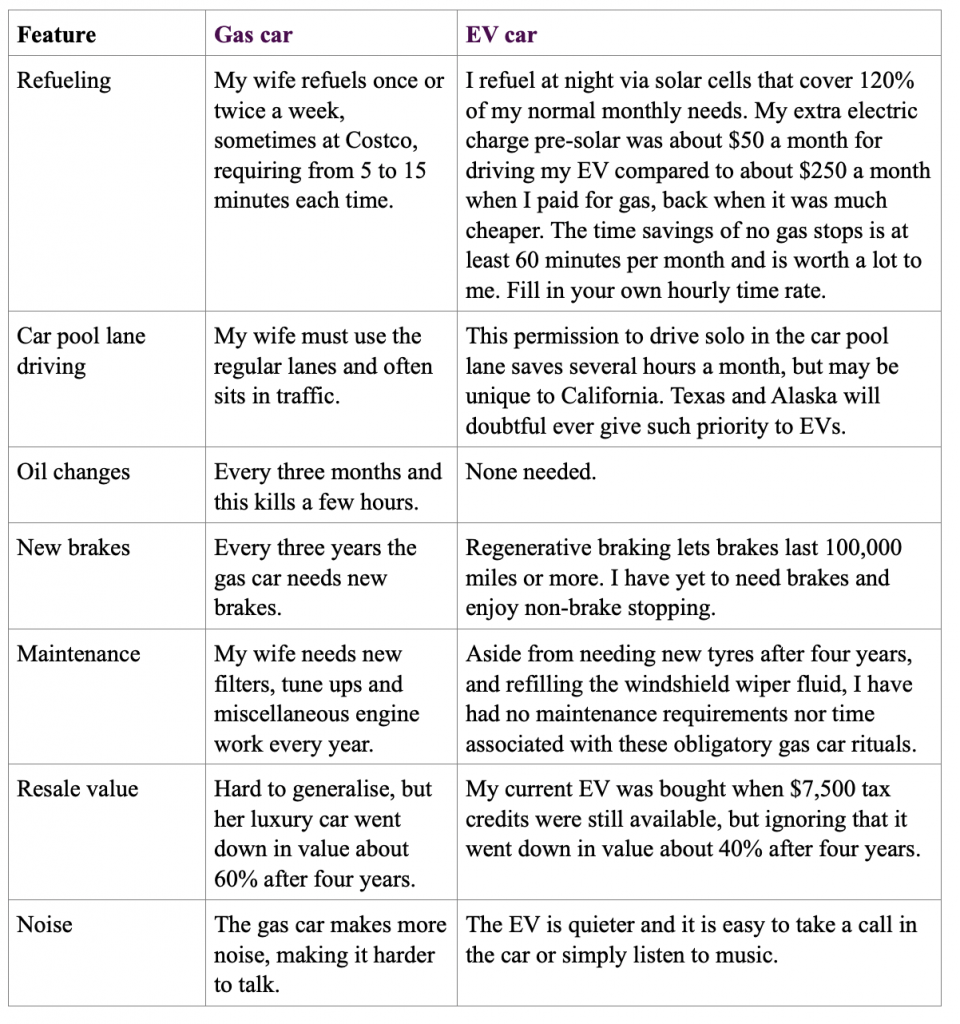

Recently, a colleague posted an opinion on social media that he would stick with his gas-powered Mustang, stating emphatically that the economics of EVs do not yet pan out. He may be right under the right set of circumstances, but in most locations, EVs are now more economical. I have driven EVs for 13 years now, owning two of them, and my wife has driven a Volvo and Jaguar over the same time span. I drive 8,000 to 12,000 miles a year and that includes some trips to wine country. My battery lasts 300 miles per full charge, with no noticeable degradation after four years and just over 40,000 miles. My navigation system blows away my wife’s car, and mine has numerous voice commands, but that could be unique to the brand. Here is what I know about the economics of my car versus my wife’s:

Conclusion

If you value your time and convenience, and can recharge at home, live in a climate that is not too cold, where you would need to use more battery for heat, then the economics of EVs are quite good. In my case, the economics of EVs in southern California are outstanding. I also like the fact that I do not pollute the air. Those of you old enough will recall the air in LA in the 1970s, or Bangkok and New Delhi today. Aside from long-term climate concerns, such polluted air kills and sickens many unfortunate residents. I admit that battery recycling will need to be addressed and I do not know how much of an environmental problem that will be in the future. At the same time, research in the labs suggests battery life will be extended by 500% within a decade. Instead of 300 miles, I would get 1,500 miles and that even blows away the hybrids.

Part 2: navigation and near-term impact

Autonomous vehicles navigate using motion sensors, multiple radar, sonar, lasers and AI (artificial intelligence) cameras. Not all car-makers are using the same combination of sensors or software. The cameras on TESLA can read traffic signs and identify objects, along with predictive analytics and high-speed computer chips allowing reactions in a few milliseconds. Tesla and most other car brands have had some autonomous driving features (cars can stay in their lane and between front and rear car) since 2014, but full-blown autonomous driving is not legal in most areas yet, except in test mode. The reason is that autonomously driven cars must be far safer than humans, not just slightly safer. If the current level of investment by Intel, Qualcomm, Tesla, Google and others is any indication, there is a high level of confidence that autonomous driving vehicles are inevitable. In theory, with the speed of adjustments possible when machines drive, cars should be far safer than when humans drive. This is not just because computers are not distracted by cell phones. The speed of adjustments and reactions to events that humans cannot even observe is far superior.

How does the navigation work? Engineers presumed for some time that to facilitate a large number of cars driving safely, a centralised control was required, and they might also point out that centralised controls are subject to cyber security problems. It turns out that this is not true. By studying the navigating mechanisms of flocks of birds that swarm together and never fly into each other, scientists have learned that birds navigate as a flock by keying off of only half a dozen or so nearby birds. Cars with the autonomous driving chips can already monitor three cars ahead and three behind and a few on each side, and this turns out to be more than sufficient for an entire peloton of cars to move in what will seem like a centrally coordinated flock.

Radar or lasers or cameras are used to measure relative distance and motion. Motion sensors are an added safety feature and cameras are the ultimate safety mechanism. As mentioned above, cameras can easily read signs and identify objects or anticipate cars coming into the planned pathway, but the real dilemma comes from choosing between the lesser of two disasters. For example, a car behind is being driven by a mother with small children and she does not appear to be braking in time to avoid your car. Your car can accelerate and ram into the car in front with only one elderly occupant. The ethical questions are enormous. Should the software be made to choose to hit a car to avoid one with more passengers? If all cars were autonomous, the good news is that accidents would decline by 90% or more. If some cars were autonomous, but not others, the reduction is far less and some autonomous cars will need to choose other cars to hit to avoid larger scale accidents. What is clear is that regulations will need to be changed to allow autonomous driving. This is most likely going to happen in stages, first with truckers, who will need to stay in their vehicles, and next with cars that drive those unable to drive themselves, such as the elderly.

Disruptions will occur. Truck drivers of autonomous vehicles permitted to drive 24 hours straight, with permission to sleep when on the open highway and with discretion on stops for food and fuel, will at first be able to make more money. Soon they will realise faster delivery times and excess capacity in the trucking system. This will lead to lower rates per mile, a more efficient supply chain and helping consumers and raising the overall standard of living for all. Truckers will end up making more money than before autonomous vehicles, but less per mile. Some truckers will be forced out of business and start to look for new jobs. Imagine the disruptions in the limo and taxi, Uber, Lyft businesses. These will be even greater. But this is the way technology improves the standard of living for all, while forcing a painful transition of those displaced.

Part 3: Real estate implications

Cars are only used 5% of the time on average. However, peak driving might involve 20% or even 25% of all cars, say on holidays and some rush hours. Traffic jams in cities like LA will still occur with autonomous driving, but the traffic will move faster and more safely. Some cars, like those for hire, will simply be on holding patterns like flights approaching a landing at a crowded airport. Parking will still be required, but some of it can shift to locations that are further away or in garages with few lights and fewer expensive exhaust fans, and park in tighter spaces. Sharing cars will allow us to own far fewer cars than today and most middle- or lower-income households will opt out of car ownership altogether, like those in big cities with good public transit. The choice of cars will be more focused on interior configurations that accommodate the size of the travelling group and their work or pleasure needs. Overall, by 2050, we will have less than half the number of cars per capita than we have now, but the variety of interiors will be far greater and the utilisation rates will parallel the desk utilisation rates in the office market, where sharing has become the norm. There will be a working mode interior, a theatre interior, a sleeping interior that the user will be able to select. Other configurations we have not yet thought of will certainly appear, but it might be helpful if widths became more standardised so that parking and car lanes can be better managed.

Because cars can drive together closer, we will be able to add a lane to a four- or five-lane highway providing 20% more capacity, while also adding more cars per length of road. Street parking capacities will likely increase, except in places like Paris or New York, where cars are already parked bumper to bumper.

Cities will need to add congestion zone tolls to prevent autonomous EVs from going into hover mode where they slowly circle city streets waiting the end of a meeting by a busy professional who wants to use their own customised work car. Singapore-style tolls should do the trick, but cities will need to pass such laws soon or else the political challenges will increase.

Multifamily property will benefit the most from reduced construction costs. Excessive parking requirements already exist in most urban markets and eliminating these can save 20% or so of a unit cost (with parking). Offices will also benefit by shifting parking to outer, less dense city fringes and on more shared locations. Those older homes with driveways and no cars will be able to provide this space for multiple cars in exchange for rental fees. Automated GPS parking apps will let you rent your extra spots by the hour with little notice. Garages in single family homes, already frequently used for storage or other purposes in warmer climates, will become a rarity except for luxury homes and car collectors. Retail properties, not displaced by Amazon or similar vendors, will have lots of drop-off lanes and short-term lots that vary in rental costs by access time. Industrial property will be the least affected of the major property types in terms of parking, but will need to be designed to accommodate driverless trucks and with electric battery or hydrogen fuel recharging facilities.

Overall, the benefits of EVs and autonomous cars include less air pollution, fewer accidents, less time wasted in cars during stop-and-go traffic, and a more productive society. While many folk we know like driving, someday soon it will be an option whether you even bother with a driver’s license. This is already true in some European cities with great public transit, but the US has had a car-centric culture and it will take longer in the US for acceptance that our driving skills have and will be replaced by machines.