Germany and some other EU countries are hastily setting up new floating gas terminals at their ports to help cope with the severe reduction in natural gas exports from Russian pipelines since the Ukraine war started nearly two years ago. To make up the shortfall, they have been buying more liquefied natural gas (LNG) from other countries, including the US and Qatar.

Adding extra floating terminals is the fastest way to increase capacity. They are required to convert the liquid gas into gaseous form so that it can be transmitted through the pipeline network to wherever it’s required. The EU’s import capacity for LNG has already been increased by nearly a quarter to just over 200 billion cubic metres per annum (bcma) since the start of 2022, and is due to go up by about another 20bcma over the winter, most of it added in Germany.

The aim is to avoid a repeat of last winter, when a 60% surge in EU demand for LNG led to a spike in energy prices that peaked at over ten times their usual levels. This was accompanied by port congestion problems from the increased number of LNG carriers, some of which were delayed in unloading as a result.

Quantifying the cost

In our recent research, we’ve been looking at how much these congestion problems affected energy prices. It’s well known that port delays of any kind are expensive: between May and November 2021 in the US alone, a combination of port congestion and a shortage of shipping containers reduced exports to the tune of US$15.7 billion (£13 billion) (it’s not known how much was caused by one or the other). When this happens, it forces companies to charge more on their products to protect their earnings, meaning prices go up.

With LNG carriers, there’s an additional problem. They can’t just sit in a port waiting to deposit their cargoes because the instability of LNG makes it dangerous for them to be stationary for more than five days. At that point, they have to either start releasing gas into the atmosphere or burn fuel by moving around in the sea while they wait for a berth, both of which cost more money.

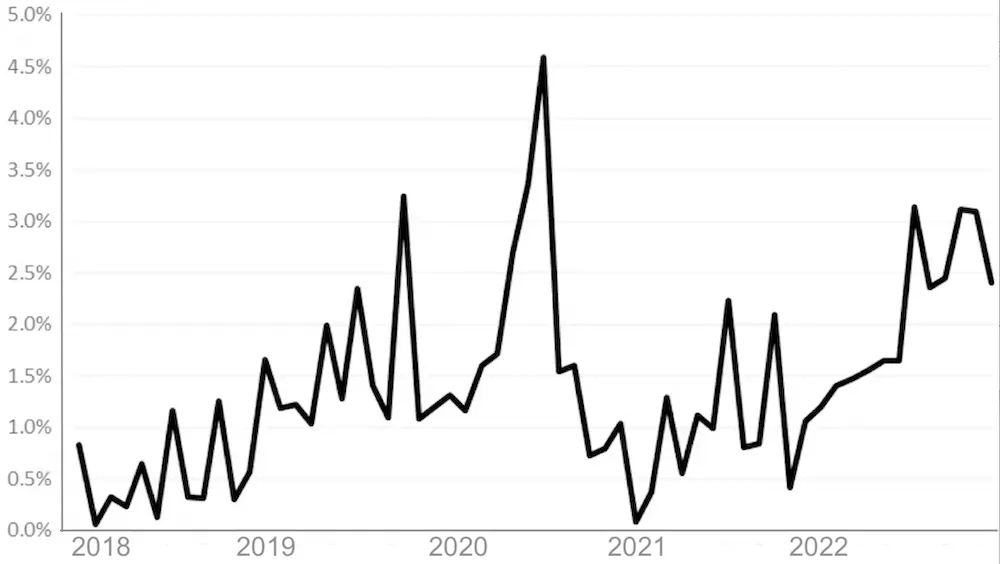

Our port congestion index below gives an indication of how LNG carriers were affected in the EU in 2022. Our data looks at the past five years, and you can actually see that there was a larger spike in general port congestion in 2020 caused by anti-COVID measures. It then eased after the first pandemic wave, only to increase again at the beginning of 2022 when the EU started increasing LNG imports.

EU port congestion index for LNG vessels

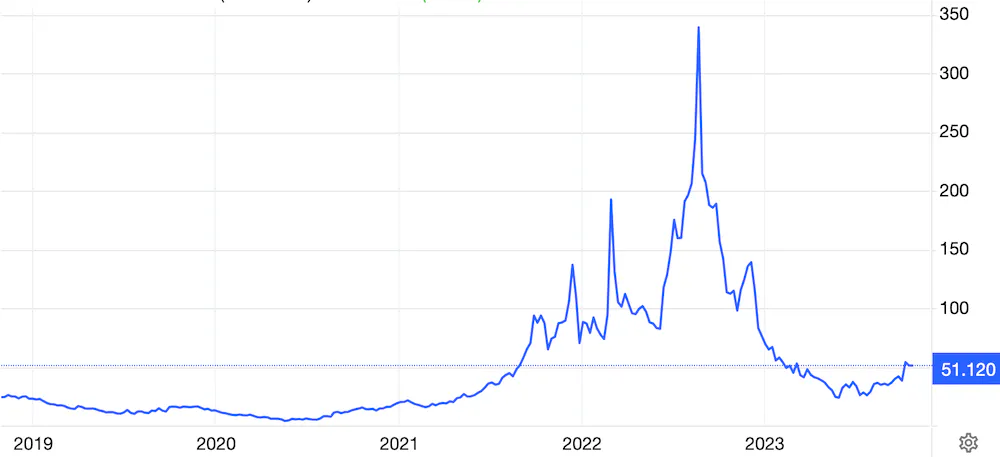

To calculate how the 2022 congestion affected energy prices, we used mathematical modelling known as econometrics. It revealed that 10% of the energy inflation in the EU was the result of port congestion. In other words, with the average cost of gas in Europe rising from circa €20 (£17.50) per megawatt hour (MWhr) before the pandemic to more like €100/MWhr in 2022, it means that about €8 can be attributed to congestion.

EU gas prices (€/MWhr)

This demonstrates how being at the mercy of the world LNG market was made worse by congestion caused by the lack of import capacity. Overall, we found that a 10% increase in the time that LNG vessels delay to berth at EU ports increased gas prices by 1%.

Notably, one consequence was that the EU had to import a lot more gas from the UK, which has the second highest LNG capacity in the region besides Spain. The UK near-doubled its imports of the fuel to pipe it to the European mainland.

The coming months

This winter, EU demand for LNG is expected to be slightly higher than last year, even assuming that projections of another mild winter prove accurate. On the plus side, EU gas storage capacity is virtually full and the extra LNG import capacity will help significantly.

If the weather is much worse than anticipated, however, gas demand will be much higher, both in Europe and in northern Asia, which is the other main region that depends on large volumes of LNG. If so, port delays could again become an issue and potentially make a similar contribution to price spikes as we have seen in the past.

The EU’s current aim is to double its import capacity to 400bcma by 2030. There are some observers saying this level of capacity is excessive when the goal is to reduce dependency on fossil fuels, but it certainly shows how far short current capacity is from where the EU wants it to be. No wonder when it makes such a difference to energy prices.

It sheds a light on the scale of the urgency around increasing capacity, as well as the need to build out alternative energy sources as far as possible to avoid similar problems in future.

This article was originally published in The Conversation and is republished here with permission.