In the summer 2023 issue of The Property Chronicle, we discussed the gathering stranded asset storm in commercial real estate, with one factor being the impact of energy performance certificate (EPC) ratings on the UK’s commercial real estate market. A question naturally follows as to what other sustainability variables could affect the performance of an asset, and by extension, valuation. With the advent of ESG 2.0 and accompanying regulations, it seems like an increasing number of sustainability variables, once measurable and comparable, will be accounted for in valuations.

A quick recap on the genesis of ESG

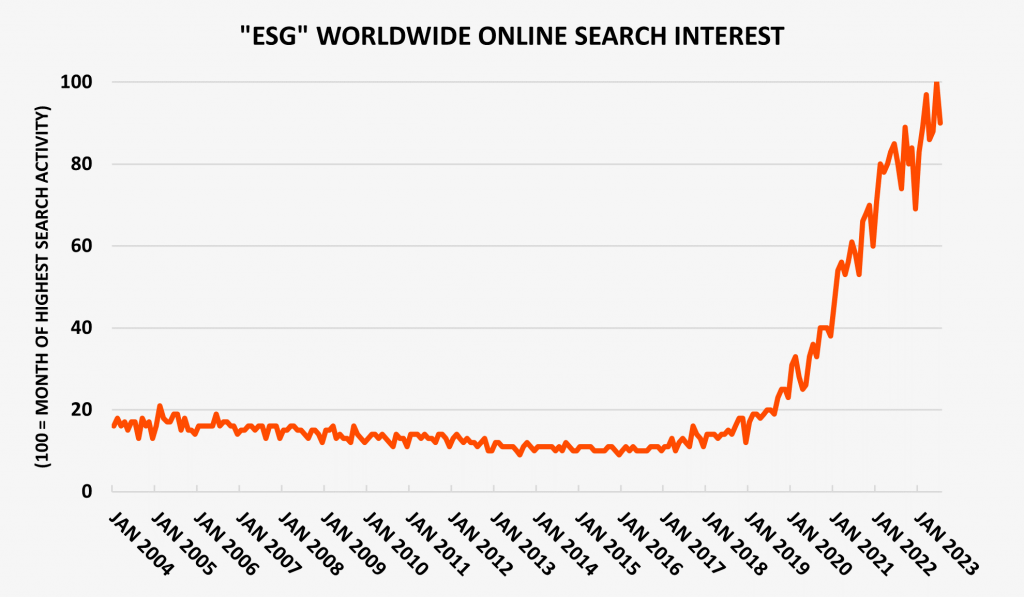

The view of the enterprise as more than a solely revenue-generating undertaking has a long history; think of Bournville, Port Sunlight, and so on. In the 20th century, anti-discrimination laws proliferated, and themes such as “ethical investment,” “socially responsible investment,” and “corporate social responsibility” emerged from the academic literature. Then, in July 2000, the UN secretary general launched the “Global Compact” as an international initiative to advance responsible corporate citizenship. Four years later, 500 leaders of enterprise, government and non-government organisations met to debate the topic of global corporate citizenship, among others. One of the major outcomes of this summit was the pledge of twenty major financial companies to “begin integrating social, environmental and governance issues into investment analysis and decision-making.” ESG, as this initiative came to be known, took until 2019 to really gain mainstream attention, as evidenced by Google Trends data (Figure 1).

Limitations of ESG

Dr Marc Lepere of King’s College Business School and Omnevue shares his perspectives on two distinct “periods” of ESG, with ESG 1.0 spanning 2004 to 2018. Lepere does not mince his words when reflecting on this period, saying that “ESG disclosures often amounted to little more than public relations or marketing.” This trend gave rise to the popularised term “greenwashing,” or more broadly, “sustainability washing.” Sustainability washing is made possible by:

- an incentive to espouse sustainability performance for

individuals and/or organisations. - a way of misrepresenting sustainability performance in

an individual’s and/or organisation’s favour.

We have seen this emerge through a “soup of ESG interpretations” said to muddy what constitutes a sustainable investment and what doesn’t, as well as inconsistent measures of sustainability performance.

Enter ESG 2.0

Beginning in 2022, Lepere identifies ESG 2.0 as being driven by regulators responding to the perceived threat of climate change, aiming to standardise definitions and metrics, and to counter greenwashing. In an initiative that aligns non-financial reporting with standards of financial reporting, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) issued its inaugural global sustainability disclosure standards in June 2023, effective for annual reporting periods beginning on or after 1 January 2024. Joining the suite of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), the first standard (IFRS S1) “requires an entity to disclose information about all sustainability-related risks and opportunities that could reasonably be expected to affect the entity’s cash flows, its access to finance or cost of capital over the short, medium or long term.”

The second standard (IFRS S2) is more specific to climate-related disclosures. Implications for real estate ESG 2.0 offers both challenges and opportunities to the real estate sector. Real estate is regularly cited as being responsible for 30-40% of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions. The sector is also responsible for a range of other sustainability-related externalities including quality of life at home and at work; the provision of housing and other in-demand spaces; industrial relations; land use and biodiversity; and many others. As reporting requirements and enabling technologies work together to increase transparency for sustainability performance, real estate professionals and their firms are incentivised at increasing levels to adopt meaningful sustainability practices. This applies to the entire value chain. In the London office market, number of certifications, photovoltaic panels, BREEAM-specific rating, and WELL-specific rating all feature as top 15 features when predicting rent level. Savills identify a similar phenomenon in other European markets, including Copenhagen where they “observed a trend towards higher rental levels for ESG-certified properties.”

Valuation and sustainability

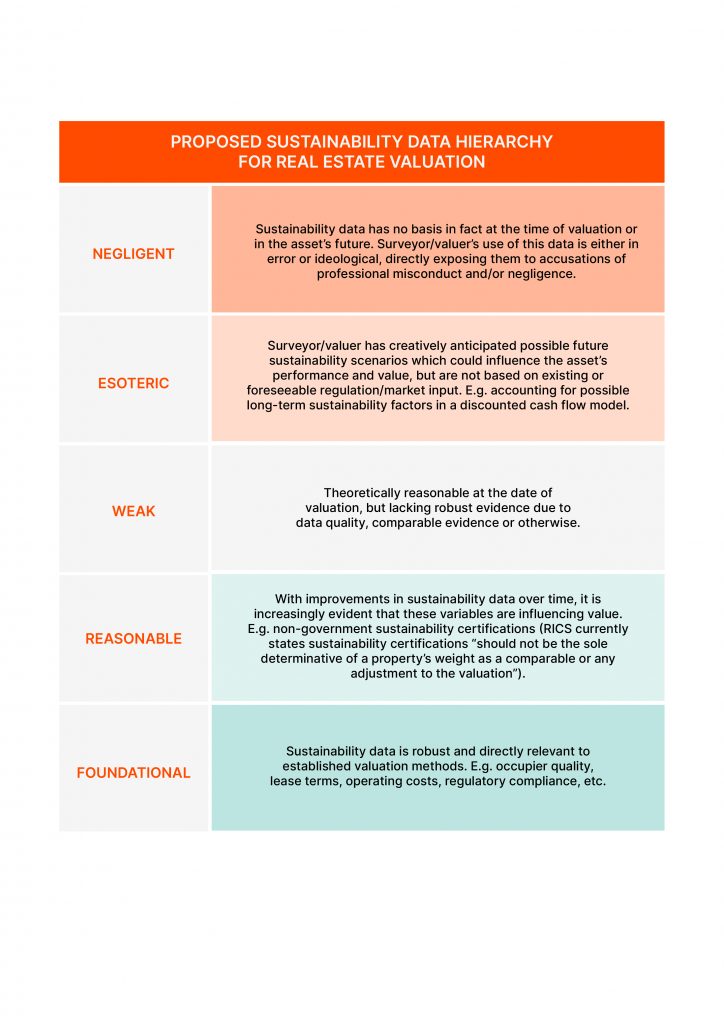

RICS offers advice to professionals on how to account for sustainability in the valuation of commercial real estate assets, including that “[v]aluers should have a working knowledge of the various ways that sustainability and ESG can impact value. These may be physical risks, transition risk related to policy or legislation to achieve ESG and sustainability targets, or simply those reflecting the views and needs of market participants”. Therefore, aside from the direct impact of net operating income on the income approach of real estate valuation, risk associated with sustainability factors needs to be accounted for in a valuation’s capitalisation rate. Until sustainability data is comprehensively as reliable as financial data, its influence on appraisals and valuations can be unreliable. For this reason, we propose a sustainability data hierarchy for the purposes of real estate valuation (Table 1).