Originally published 6 July 2022.

Having claimed the UK will avoid such a fate, I want to explore whether Continental Europe can avoid falling victim to recession. To do so I consider 10 channels through which the recession virus could spread across the Continent and, worse still, its stagflation variant. Let me make clear this is not an exhaustive list of how the EU will succumb to recession. Indeed, it would not need all 10 to happen in short order for recession to be induced.

1. European monetary efforts to ‘deal’ with inflation will actually sow recession.

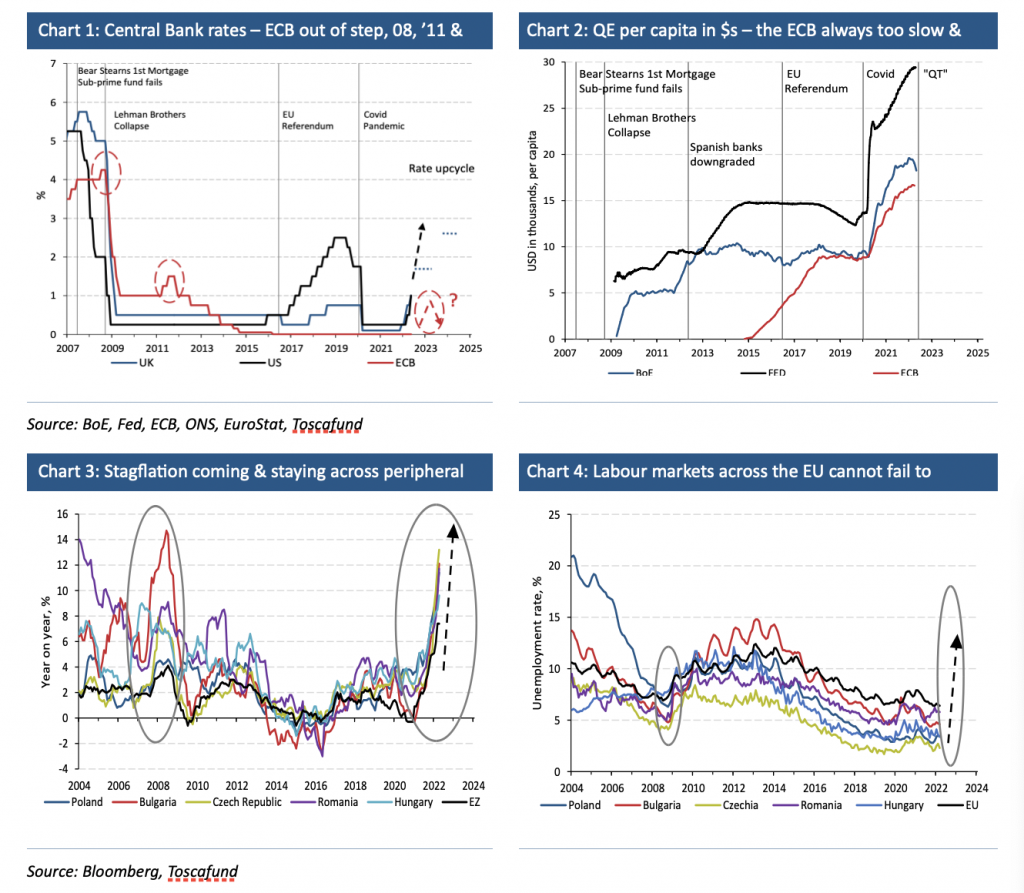

I am convinced that at a time when the EZ needs to continue with ultra-loose monetary policy, the ECB will make the mistake of tightening. This would not be the first error of its kind, the ECB repeating its mistakes of 2008 and 2011 (see charts 1 and 2).

2. As the ECB pushes rates into positive rate territory, however modestly, it will force a rate response from central banks overseeing policy in nations within the EU but outside the single currency, but very much close to events unfolding in Ukraine (10.0%, 7.5%).

Spare a thought for those EU nations outside of the euro for whom events unfolding within Ukraine are very close to home. I write here of Hungary (5.4%, 9.5%), the Czech Republic (5.75%, 13.2%), Romania (3.75%, 11.7%), Poland (5.25%, 11.4%) and Bulgaria (0.0%, 12.1%). For the most part these nations have already experienced monetary tightening, as reflected in the bracket numbers showing where rates of interest and inflation respectively have most recently reached. As the cost of money and/or goods rises to ever more elevated levels, the capacity to spend cannot fail to fall. And across the EU, these two forces have been rising sharply. These are states whose inflation cost problem will not be eased by raising rates, but rather whose economies will be forced into deeper recessions as a result.

3. Well after hostilities cease – and we can yet see no end in sight – events in Ukraine will continue to take their economic, financial and humanitarian toll across Continental Europe.

Be in no doubt what continues to unfold within Ukraine has direct adverse economic consequences on the EU. We witnessed sharp upwards shocks to energy and food costs, disruption to trade and tourist flows, and a considerable humanitarian crisis, all of which have negative economic consequences.

4. Having devalued, Ankara will be forced to devalue again.

Turkey (14.0%, 70.0%) is heading for a truly awful economic crisis. To be clear, the last inflation print in Turkey was 70.0% (see chart 3 for context) with foreign reserves of dubious provenance standing at $61.2bn and falling fast. A Turkish economic and financial crisis is one that cannot fail to distressingly spill over into its neighbours and competitors in multiple ways.

5. The contagion from Ukraine will not stop at Turkey.

Egypt (11.25%, 13.1%) isn’t that far away from Turkey, geographically or economically. It too will devalue and provide its own competitive shock to the eurozone and wider EU. Before long, Tunisia (7.0%, 6.6%) will also be forced into a devaluation and so too will other nations close enough to the eurozone to negatively impact it.

6. If events move as quickly as I expectantly fear, we could easily see structural breaks within the EU. I am not writing of ‘exits’ per se, but significant devaluations.

In identifying the most likely EU currency to move materially lower against the euro, my nominee would be the forint. We could well see a domino effect as neighbouring currencies join the downward cascade.

7. It is possible the UK Government unilaterally tears ups the Northern Ireland protocol. If it does, the EU could well decide that the entire Brexit trade deal is void.

A trade war between the UK and EU could hardly come at a worse time. And while a trade war with the EU would come with negative consequences for the UK economy, a weaker pound would act as a shock absorber of sorts, as it has done regularly since 2008. This would deliver a financial and economic blow to large tracts of the EU. A weakened pound and disruptions to trade with and travel from the UK would be economically very unwelcome.

8. I have identified a host of events close to home which expose the EU to the looming prospect of recession. Let me now turn to events far beyond Europe and its neighbourhood.

While we have seen a great many fiats tumble against the dollar, the yen has been a particularly noticeable currency causality. For the EZ’s mercantilists, a more competitive capital and consumer-good making rival could hardly come at a worse time.

9. When I wrote earlier of the EU being hit by structural breaks, I stopped short of predicting a Brexit type exit. Well, as much as this is not likely any time soon, I would not dismiss it in the years ahead.

If some of the events outlined above unfold, we could see an EU nation defecting for a host of self-interested reasons – Hungary. Although I would not exaggerate the economic importance of Hungary leaving the EU, it would hardly deliver positives.

10. Although the figure could be anything between 500,000 and 750,000, it is considerable. I write here of the number of EU nationals with settlement status in the UK who are not presently living or working within it.

I have absolutely no doubt a great many of those Europeans who left the UK when the pandemic struck will return. As this flow happens, it will benefit the economy of the UK but further blight the EU nations being left behind.