With the PSOE coming out on top, Spanish prospects are only looking up

Pedro Sanchez’ gamble to call a snap election has paid off. His PSOE (the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) has become the biggest party in parliament, with its share of the vote at least 10 percentage points ahead of any other. Yet, one is left with a lingering sense of fragmentation, especially on the right. And the PSOE will struggle to form a coalition without confronting the Catalan independence issue.

The economic cost, however, is not likely to be too high. Spain’s budget deficit may rise a little this year if negotiations drag on, but as long as the country’s relative growth rate holds up, we don’t expect Spanish yield spreads to rise much. The euro remains short against the US dollar.

The outcome of Spain’s April elections turned out to be calmer than many had feared. Pre-election opinion polls proved reasonably accurate. The centre-left PSOE led the way with 28.7% of the vote, while the rest of the field were evenly matched. The left-wing Unidas Podemos (14.3%) and centrist Ciudadanos (15.9%) did a bit better than expected in recent surveys, centre right Partido Popular (16.7%) and ultra-nationalist Vox (10.3%) a bit worse.

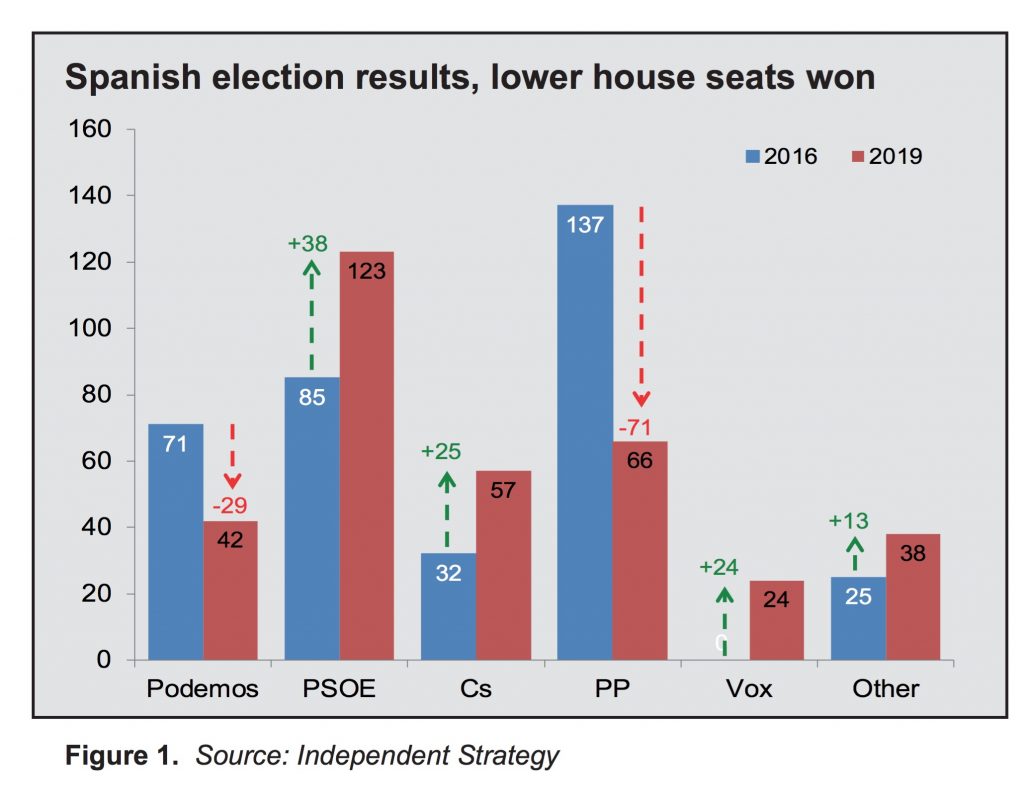

The left came out ahead overall and, in comparison to the split of their combined vote after the 2016 election, there was a clear swing away from the fringe back towards the centre (figure 1).

This contrasts with the fragmentation of the right. The fall from grace of the Partido Popular, the centre-right’s traditional mainstay, has been dramatic. As recently as 2011 they’d secured 44.6% of the vote, and with it a comfortable working majority of 186 seats in the lower house. On Sunday, their share of the vote collapsed to a record low of 16.7%, or just 66 seats.

Much of that gap has been filled by the pro-business Ciudadanos and a recent surge in support for Vox. But, as we’d anticipated in our last report on the 19th February 2019, ‘Spanish f(ar-)right’, this proved anything but a populist uprising.

PSOE leader Sanchez is now in the driving seat. While he secured a majority in the Senate, he needs 176 seats to gain a majority in the Congress of Deputies. Together, the two natural allies of the left – PSOE with 123 seats and Unidas Podemos with 42 – are 11 short of a majority.

Ideally, Sanchez would like to avoid that old chestnut of Catalan independence. Unfortunately for him, the smaller anti-independence parties only secured 10 seats between them, while smaller pro-independence parties gained the remaining 24. So this simmering sub-plot will continue to haunt coalition discussions.

If we exclude any likelihood of a grand coalition, the only other mathematical possibility is a tie-up between the PSOE and the Ciudadanos, which would, in theory, command 180 seats. But with the Ciudadanos looking to become the loudest voice on the centre-right in the wake of the Partido Popular’s demise, that outcome is unlikely to materialise.

So we’re back to the same situation as before. Whether it leads to another unstable, minority PSOE-government, or a formal coalition, remains to be seen. A period of horse-trading is inevitable.

How much does all this matter? After all, the Spanish economy grew at a revised 2.3% year-over-year rate in 2018’s fourth quarter, compared to just a 1.0% year-over-year rate for the rest of the Eurozone. And Spanish unemployment has fallen from a peak of almost 27% in 2013, to just 14.7% now.

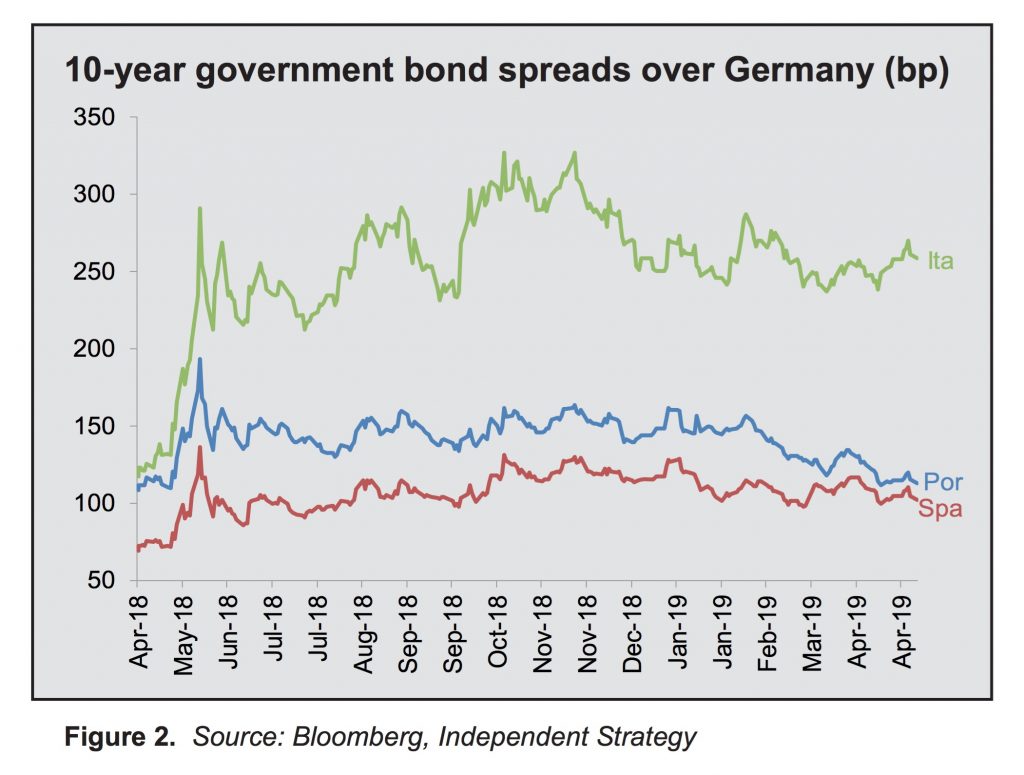

The main immediate area of policy concern is fiscal. The 2019 budget failed to pass before parliament was dissolved. Its deficit target had been set at around 2.1% of gross domestic product (GDP). Agreed pension and wage increases mean that this will rise to perhaps 2.4% of GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund, based on a continuation of the 2018 revenue parameters. So there is a cost to delay, but it is hard to argue that this will be destabilising. Indeed, over the last couple of months, Spanish 10-year bond yield spreads over German bonds have actually narrowed from 112 basis points (bp) to just over 100bp, despite election uncertainty (Figure 2).

Longer term, this outcome highlights the broader theme of political fragmentation and the threat of populism in Europe. The shifts we’ve seen across much of the continent in recent years look set to continue, with the UK probably the next fall-guy. All eyes, then, turn to May’s European parliament elections.