This integrated approach offers a handy way to tailor risk/return solutions in the current market.

Back in 2003, Susan Hudson-Wilson, Frank Fabozzi and Jacques Gordon wrote an influential academic paper entitled “Why Real Estate?”, which articulated the idea that the universe for real estate investors should be expanded from the traditional realms of private equity and private debt to include the ‘new’ public equity and public debt markets. Thus the concept of the quadrant model was born.

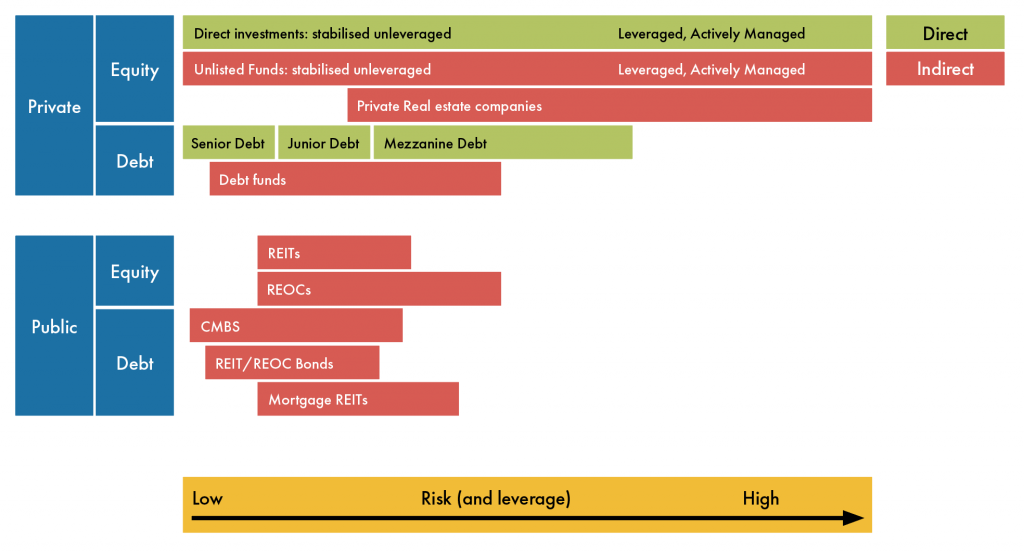

It is often referred to as ‘the four quadrants’, but the tautologically astute might reasonably enquire how many quadrants there should be if not four, so we will refer to it merely as the quadrant model. The idea is straightforward: to divide the real estate investment opportunity set into public and private options, as well as debt and equity options.

Given that the US is the largest and most liquid real estate market globally, and that Wall Street practitioners are never shy of repacking assets into ever more complex products, it is not surprising that this approach has most relevance – and indeed most components (particularly on the public debt side) – in that market. Nonetheless the quadrant model is also applicable to the UK, Europe and the Asia-Pacific, with slight variations.

As well as looking at the available opportunities, we can also use the quadrant model to understand the risk/expected return framework for each of the components. The table below shows how this segmentation operates in practice.

These four categorisations on the axes of public/private, debt/equity represent very different ways of participating in the returns of the underlying asset, and themselves provide a very different (but clearly related) risk and return profile from the ungeared, underlying real estate. While equity participation via listed vehicles and unlisted funds has been well established, most recently there has been increased interest in participation in debt secured against the underlying asset. The questions we need to ask now are: who is using this integrated approach, how are they using it, what are the problems and why is it relevant now in particular?

So, first, who is using it? Historically the biggest users have been the larger pension funds (APG, PGG) and sovereign wealth funds such as GIC, all of which have successfully adopted an integrated investment approach that allows them to invest across the capital stack, albeit with slight differences in strategy. As a result, at the same time they might hold equity in a listed company as well as its corporate bonds, while also being a senior debt provider and holding a share of a fund/joint venture with the company.

How are people using it? There are three particular strategies employed. The first is investing for the longer term across some or all of the quadrants to provide the required risk-adjusted portfolio return. The Legal & General Hybrid Fund, which combines a UK property fund with a global REIT tracker for DC pension funds, is a good example of this.

The second strategy is switching between the different quadrants according to relative pricing. Funds have been set up to operate these strategies – in a kind of property arbitrage model – but have typically failed to gain traction with investors. Under the third strategy, an asset management company may start out in one quadrant (say, private equity) and then decide that the next fund would offer better returns in another quadrant (for instance, private debt).

What are the problems with the quadrant model approach? There are three main areas of difficulty. Firstly, employing a team that has the skillset to understand the dynamics and pricing of each of the four markets and arrive at an unbiased conclusion. Secondly, compliance – or rather the potential lack thereof. Listed fund managers can only deal on publicly available information, and this can be an issue if another part of the team (such as private debt or private equity) are negotiating a transaction with a company where the equity manager wishes to trade the shares. Thirdly, timing and liquidity: while there may be pricing opportunities across the quadrants, timely execution can be a problem.

The idea is straightforward: to divide the real estate investment opportunity set into public and private options, as well as debt and equity options

So, why is the quadrant model of particular relevance at present? There are three main factors driving the move to re-examine the model and apply it in the current environment. The first is that the pricing vacuum caused by low transaction levels has led to an apparent disconnect between public and private equity markets. This has seen private equity operations such as KKR take a stake in Great Portland Estates.

The second factor is that the caution of senior lenders coupled with continued appetite for the sector has led to a gap between the supply of senior debt LTVs available and the demand from asset owners. As a result, new players are entering into the whole loan and mezzanine finance market to enhance senior LTVs to levels that would provide acceptable returns and minimise the equity capital deployed.

The third reason for the quadrant model’s present appeal is a desire by some investors to improve liquidity (by adding public market exposure), while others have sought to reduce volatility and improve risk-adjusted returns by allocating capital away from public markets to private markets.

How is this likely to play out? For reasons of liquidity it is not realistic to operate a permanent arbitrage model between the four quadrants, but we are likely to see continued use of blending different quadrants to provide specific risk/return solutions, as well as seeing well-known and respected real estate managers in individual quadrants branch out in a more holistic and integrated manner.