Originally published May 2023.

Innovations in fractional ownership and use of space

Fractionalisation means many things to many people. Shares in REITs, syndicates, tenants-in-common, even land subdivision and strata title are all examples. Since the mid-2010s, we have seen a surge of technology-enabled fractionalisation platforms in real estate and beyond. US-based Pacaso is often cited within this cohort of startups. It was founded in 2020 by Austin Allison (Dotloop) and Spencer Rascoff (Zillow Group). Via this platform, you can own a one-eighth share in a multimillion-dollar holiday home of your choosing and enjoy it 44 days per year. In 2021, Pacaso’s $125 million Series C fundraise led by SoftBank valued the company at $1.5 billion. More recently, Kō has made waves with a comparable business model in the Asia-Pacific region. Other platforms haven’t been as fortunate, with an expanding graveyard of fractionalisation initiatives which didn’t quite make it before their well of funding ran dry. This prompted some months of research, culminating in a white paper titled ‘A piece of the action: innovations in fractional ownership and use of space.’ The goal? Gaining a better understanding of how fractionalisation platforms differ to one another and based on these variables, which platforms offer more promise than others. Our analysis included 165 fractionalisation “schemes” (individual investment products) around the world—spread across residential, commercial, land and other (see Figure 1). Approximately three-quarters of the schemes were equity investments, with the remaining quarter debt.

Approaches to fractionalisation

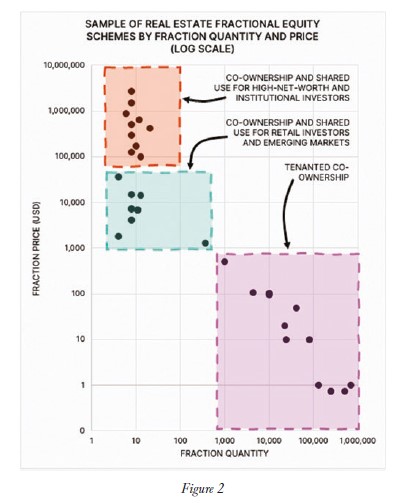

When comparing one scheme to another, the relationship between fraction price and fraction quantity is an insightful starting point. In the case of Pacaso and Kō, fraction prices are high (up to and exceeding $1 million) and the fraction quantity is low (eight per property).

This contrasts with Ark7, for example, where fraction prices are low ($20) and fraction quantity is high (22,500 in the case of a particular scheme analysed). Consequently, a difference between these platforms is that Pacaso and comparable models facilitate shared use for fraction holders, whereas the likes of Ark7 couldn’t possibly do this effectively (one fraction in an Ark7 property would be equivalent to about 23 minutes of time each year). This is an important distinction, because while the likes of Pacaso facilitate shared use (a non-financial return), the likes of Ark7’s lower emphasis on non-financial return will lead investors to emphasise financial return.

Non-financial return

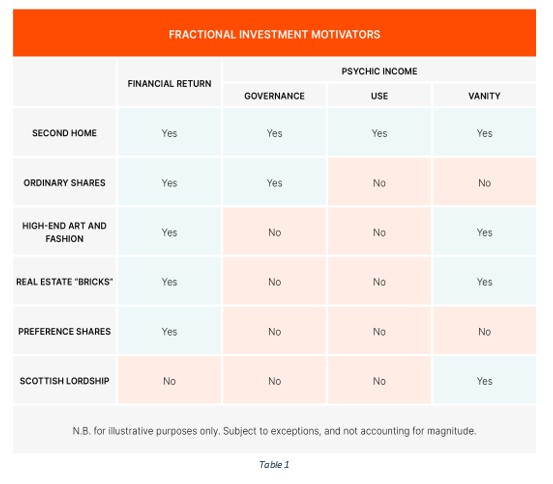

Democratisation, the process of making investments or other valuables accessible to more of a population, is cited as one of the key value-adds of fractionalisation platforms. Returning to the example of co-owned second homes, instead of concentrating a large bulk of capital to fully own an asset you use for only a fraction of the year, why not purchase a fraction in proportion to the level of your intended annual use? The compromise? Scheduling use with your co-owners. Aside from use, our research identified other non-financial motivators. Governance is a familiar non-financial motivator in fractionalised ownership (shares) of companies, with the board of directors representing shareholder interests. Governance also applies to real estate fractionalisation. CityDAO, for example, is attempting to build a community governed “crypto city of the future” in Wyoming, USA. Another non-financial motivator we identified is vanity. What level of street cred do you get for coowning a Banksy painting? Or, closer to the real estate world, would you pay more than the price-per-square-foot of prime London residential space for the privilege of a square foot of land entitling you to a faux Scottish lordship?

Financial returns

If you check 1- and 2-star reviews of fractionalisation platforms on Trustpilot, a common theme you’ll observe relates to investors exiting their positions and the complications in doing so. A particular platform, which announced closure of its funds in mid-2021, was accused of taking in excess of two years to return capital to investors. In other cases, complaints have been made that secondary market sales took longer than advertised, and/or required significant discounting to achieve a sale. This appears to be a particularly salient risk for a certain use case within the fractionalisation movement which we refer to as “open-ended fractional equity for financial return”. Although these schemes offer retail investors the opportunity to mitigate against idiosyncratic risk inherent in large direct investments such as a first or second home, salient challenges include (i) dependence on robust secondary markets; as well as (ii) whether customer lifetime value justifies the customer acquisition cost; (iii) the impact of acquisition and ongoing costs on total return; and (iv) how fractionalising an asset impacts liquidity. Otherwise, for fractionalisation schemes targeting financial return, we saw much more traction when secondary markets weren’t as necessary (or even redundant). Examples of this include debt or equity in value-add projects with natural exits such as crowd sourced development finance.

Outlook for the future

If past performance is anything to go by, the outlook is bleak for fractionalisation platforms offering a high quantity of low-priced shares in single assets or portfolios without a natural short-term exit. In the absence of large institutional cheques, these platforms have largely failed to scale, and we expect this to continue. A possible exception is for emerging markets, where such platforms could compensate for the

absence of REITs. Even so, the cost of building enough of a user base, and the limited advantage of a user trading real estate shares at high velocity, prompts scepticism. This could all change if resources were dedicated to building out a central, robust secondary marketplace—as OpenSea did for the non-fungible token sector and listing platforms (such as Zoopla and Zillow) did for direct real estate purchases. In the meantime, if financial return can be quantified and realised without the need for a secondary market, fractionalisation serves as a means of democratising otherwise inaccessible asset classes (such as real estate development projects). Finally, non-financial return has played a significant role in the success of fractionalisation platforms, and we expect to see platforms with this offering achieve scale in the coming years. To read more about this research, visit pilabs.vc/insights