Earlier this month, the UK and Ghana announced the signing of a long-anticipated bilateral economic partnership agreement (EPA) aiming to replicate pre-Brexit trading arrangements and provide for the two countries’ respective long-term economic ambitions.

To quote UK authorities, the deal means that: “Ghanaian products including bananas, tinned tuna and cocoa will benefit from tariff-free access to the United Kingdom. UK exports are also in line to benefit from tariff liberalisation from 2023, including machinery, electronics and chemical products.”

Regulatory clarity is the agreement’s most immediate benefit. And one not to be sniffed at. Of Africa’s 54 countries, Ghana is the region’s ninth-largest economy and the UK’s ninth-largest trading partner (at least in terms of merchandise trade). Ghanaian-British bilateral trade flows in 2019 were valued at £1.2bn, according to figures provided by the British government. The £204m stock of UK foreign direct investment (FDI) in Ghana and £1m stock of Ghanaian FDI in the UK are additional pillars of the relationship.

Looking forward, there are reasons to believe that the potential for the relationship is larger than the status quo

Looking forward, however, there are reasons to believe that the potential for the relationship is larger than the status quo. At 7.1% and 4.1% year-on-year, Ghana’s average annual GDP and real per capita GDP growth was the third-fastest in the entire region between 2009 and 2018 – behind Ethiopia and Rwanda. Recently discovered oil and gas resources are an important part of that story (production began in December 2010).

But so too are technology and financial services, areas in which UK companies perform particularly well globally. Between 2014 and 2017 alone, the number of Ghanaians with a bank account grew from 41% to 58% of the population above 15 years of age, per World Bank estimates. Mobile money is a major cause of this expansion of financial services to the previously unbanked.

Today, an estimated 40% of the 15-plus population has a mobile money account. Evidently, there has been growth, and evidently there is room for more. Ghana is also a member of the African Continent Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which began implementation in January. In fact, Ghana plays host to the AfCFTA secretariat. Given the 53 other AfCFTA members, this will be the largest regional trade agreement in the world by number of countries, covering a 1.2 billion population and US$2.3tn market. In recent weeks, with the help of the Ministry of Trade, a number of Ghanaian companies were able to export goods to Guinea and South Africa under AfCFTA arrangements; and goods were received from Egypt under the same.

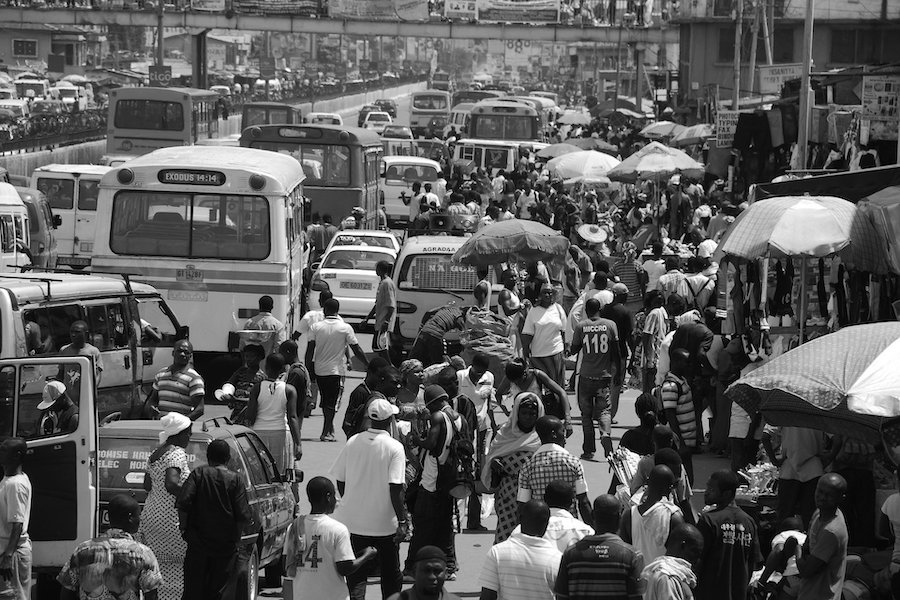

There is still a lot of ground to cover to make AfCFTA a meaningful reality. For example, protocols on rules of origin are still being negotiated while current physical, bureaucratic and logistical barriers to trade are daunting. The relationship between AfCFTA and the UK-Ghana EPA will also have to be clarified (as well as those signed by 15 other African countries). Nevertheless, work is being done. And if realised, it would present a secular change in Africa’s economic calculus.

Meanwhile, Ghana is grappling with structural challenges exacerbated but not caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Chief among them are public financial management and economic diversification. On the first point, Ghana’s fiscal strain is best encapsulated by two figures – public debt at 76% of GDP and an 11.4% of GDP fiscal deficit. Action is required.

In the 2021 budget read out just last week, the government proposed a number of measures to rationalise expenditure, such as increaing fuel levies. Key constituents are pushing back on elements of the bill. In the context of a novel hung parliament, the government may be forced to compromise. Whatever emerges from those negotiations, state agencies with revenue collection responsibilities will be applying themselves to the task with energy. This actually increases the need for digital transformation services.

And on the second point, manufacturing accounted for around 10% of GDP when Ghana won its independence from the UK in 1957 and is around 11% today. The current president, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, has spoken about the need to industrialise at every opportunity. Ghana won early plaudits for its covid-19 response but is far from unscathed. As a result of border closures, local restrictions, supply chain disruptions and export price volatility, economic growth in 2020 dropped to an estimated 0.9% year-on-year. That’s better than the outright contraction in larger economies like South Africa and Nigeria, but it is painful all the same.

International oil prices have picked up from their 2020 lows but given much of the world’s plans for decarbonisation, the sector looks vulnerable. In sum, then, there is a need for new valued-added activities employing and training Ghanaians. And on all these fronts, there is room for partnership. Forging these is a potential source of comparative advantage.