Originally published May 2021.

The long view of property.

In light of the latest review of the long-term economic and financial market outlook, Capital Economics recently revisited our views for commercial property performance over the next few decades. Given the shake-up the industry has received since the advent of Covid and fears about the impact of structural change, there were good reasons for trepidation. But we found the changes to our pre-virus view were surprisingly modest. Most important, though we think that average returns will be lower than in the recent past, property will remain attractive relative to other financial assets.

We recently launched a new long-term forecasting service, The Long Run, which extends our economic and markets views through to the middle of the current century. As part of this work, we updated our long-term predictions for commercial property beyond the current decade and up to 2050.

Risky assets like equities and real estate (proxied by REITs) will continue to do well over the next 10 years

Our long-run asset allocation analysis compares the performance of a range of financial investments, including property. The broad view there is that, despite returns being lower than in the 2010s, risky assets like equities and real estate (proxied by REITs) will continue to do well over the next 10 years.

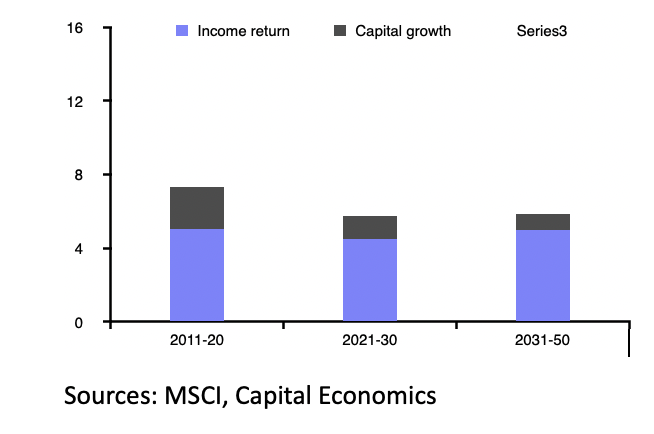

Admittedly, there are concerns about current stock market valuations, but relative to bonds these seem sustainable. Similarly, for property, while yields in some sectors are still near to historic lows, we think the asset class will offer decent returns relative to bonds – at about 6% pa on average globally – given the drift upward in inflation and interest rates that is expected over the next decade or more (see chart below).

It is tempting to see post-virus structural change as the reason for this step down in property performance. This will certainly be a factor in differences across commercial sectors, notably for retail and offices, but our latest global forecasts are not much different from what we were expecting pre-virus. A year or so ago, we saw somewhat better rental prospects in the 2020s, but also more limited yield rises, so returns were broadly similar.

Looking further ahead, nominal property returns are expected to stay close to 6% pa, though with a slight shift in their composition. By the late 2020s, steadily rising global bond yields are set to bring higher property yields, which then continue to edge up over the forecast. This negative yield shift weighs on capital value growth from 2030, but is offset by higher income returns, so total property returns are little changed.

There is, of course, huge uncertainty in projecting over this horizon and we would point to two alternative scenarios. First is that interest rates could rise more slowly than we expect, as has consistently been the case over the recent past. By providing scope for further falls in property yields, this could improve returns, but given that bond rates cannot go much lower, unless this compression were sustained indefinitely, any benefits are likely to be at least partly reversed at some point in the future.

There may be an upside to property rental growth longer term, as global inflation rises

A second risk is that we are too pessimistic about rental growth. We use real GDP to forecast rents, not inflation, as historic relationships are much stronger. But some argue that there is also inflation protection in rents due to indexation. This effect will clearly vary between markets, but gives a hint that there may be an upside to property rental growth longer term, as global inflation rises.

So, while property performance is expected to be weaker in absolute terms over a 30-year horizon, the big picture is that it should hold attractions for investors, maintaining its historic long-term returns ranking between bonds (lower) and equities (higher).

Drivers of global all-property total returns (%)