With the bull market scaling new heights and global growth re-accelerating, I explained last month why this situation is likely to continue (see Why The Bulls Are Back In Charge). But I noted at the end of that paper that, as investor sentiment becomes increasingly bullish, it will become appropriate to focus more analytical attention on the risks that could disrupt these positive trends, while still retaining a risk-on asset allocation that reflect by far the most likely scenario, which is simply that the positive trends of the past decade will continue for at least another year or two.

This is what I did in November 2017 (see Goldilocks And The Ten Grizzly Bears). Without pretending to have any kind of crystal ball to predict the future, I listed 10 macroeconomic, political and valuation issues that were already becoming apparent by that autumn, and which carried the risk of becoming much more serious in the year or two ahead. These provided a useful framework for thinking about the market turmoil and economic surprises of 2018.

Here, then, is my attempt to repeat that exercise by looking at 10 worries that are currently bothering investors, which may or may not intensify into serious problems in the second half of 2019 and 2020. Today, I will merely summarise each in a few paragraphs to create a risk framework which clients will hopefully find useful and which I will update in the coming months. In each case, I attach my subjective guess of the probability that the risk will materialize in the next 12-18 months and become a serious obstacle to the continuing bullmarket.

Macroeconomic risks

Significantly weaker growth in US or China (<10%)

A US recession and/or Chinese financial crisis appeared to be the main cause of the market panic last December and many investors still believe that a US economic expansion now entering an unprecedented 11th year must be living on borrowed time.

There is, however, no empirical evidence or theoretical basis for the idea that economic expansions die of old age. Post-war US expansions have varied in length from 12 months to 120 months – and 212 months excluding the effects of the 1990-91 Kuwait war. And the present expansion in Australia, which is one of the world’s most inherently cyclically economies because of its exposure to commodity prices and property speculation, is now in its 29th year and still going strong.

Recessions are usually caused by monetary or fiscal tightening or financial crashes. But major US policy tightening is almost inconceivable until after the 2020 election, and the Chinese economy is only just starting to respond to the policy easing of late last year.

Of course, in the pre-Keynesian world, where business cycles were driven by capital investment, rather than monetary and fiscal demand management, recessions usually occurred because entrepreneurs ran out of profitable investment opportunities. But this kind of classical – or Wicksellian – recession has rarely occurred in the post-war period. And despite last year’s panic about a recession caused by deteriorating business “animal spirits”, data from the US and China showed very little sign of major weakness in the second half of last year. My conclusion, therefore, is that a recession or major slowdown in the US or China is very unlikely, even in the event of a further escalation in the trade war (a risk I return to below).

Recession in Europe (25-50%)

The data from Europe unfortunately tells a very different story. In the second half of last year, while investors were needlessly fretting about the US, China and emerging markets, it was Europe that was actually sinking into stagnation, or outright recession. This could be seen in the revisions to the International Monetary Fund’s 2019 growth projections to take account of data releases in the past six months. While projections for China and the US were essentially unaltered, growth in the European Union was downgraded by 0.6pp to 1.3%, in Italy by 0.9pp to only 0.1% and in Germany by a whopping 1.1pp to 0.8%.

To make matters worse – and the threat of a European recession much greater – the EU has, as usual, responded to weak data with exactly the wrong policies. While the Chinese and US authorities can usually betrusted to respond to weaker data by boosting demand, the instinct in Europe is to do the opposite. Instead of counter-cyclical monetary, fiscal or credit easing, the eurozone policy response is almost invariably pro-cyclical. The European Commission tries to force Italy to cut public spending and raise taxes; the German government cites narrowing budget surpluses as an excuse to cut investment; the European Central Bank stops bond purchases, and bank supervisors respond to a credit crunch by pressing banks to raise capital and increase provisioning for non-performing loans.

These policy responses largely explain why the eurozone has spent half the post-crisis decade in recession, while the US has enjoyed an unprecedented period of uninterrupted growth. And if a recession does hit Europe it could easily trigger a global financial crisis because of the weakness of the European banking system and the EU’s instinctively perverse policy responses.

In the present downturn, however, there are two glimmers of hope. Firstly, Germany is now taking over from Italy as the EU’s worst-performing economy. This is good news because Germany’s economic problems will encourage more expansionary domestic policies, as they did in the 2008–09 recession, and may even dissuade German politicians from inflicting unnecessary austerity on their trading partners, as they did during the 2010- 13 euro crisis, when Germany seemed immune. Secondly, EU institutions are facing an unprecedented existential threat from populist politics – and as a result dangerously pro-cyclical austerity policies are less likely than in previous economic downturns.

Combining these political pressures for slightly more rational macroeconomic management with the generally decent conditions in the global economy, an outright recession in Europe is unlikely. That is why my base-case scenario for asset allocation is a modest economic recovery in Europe, which in turn should trigger strong temporary rebounds in European cyclical assets badly beaten down by last year’s terrible data surprises and the still very negative expectations for the year ahead. But even if the probability of an EU recession or financial crisis is well below 50%, we should recognise that most of the risk to the world economy lies in Europe, and Europe is the region that bullish investors must watch most carefully to decide when to draw in their horns.

The Fed’s dovish U-turn becomes a hawkish S-turn (<10%)

December’s shift in US monetary policy was arguably the biggest and most abrupt U-turn performed by the Fed since August 1982, when Paul Volcker suddenly abandoned monetary targeting in response to the Mexican debt crisis. Since there was no sudden change in US data between the first week of December, when the Fed was outspokenly hawkish, and the last week, when it turned unequivocally dovish, the main explanation for last year’s U-turn must have been that month’s dramatic movements in financial markets.

Butifa-12% plunge in equity prices and a brief inversion in part of the yield curve was enough to force a dovish U-turn, isn’t it possible that a powerful bull market on Wall Street and a steepening of the yield curve could provoke an equally abrupt shift back to hawkish policy?

Such a hawkish U-turn seems unlikely in the next 18 months, partly because of political pressures ahead of the 2020 election, brutal so because of a genuine intellectual shift in the Fed in favor of a more symmetrical inflation policy that would require an extended overshoot of the 2% target. So this is a low probability risk, but investors should keep it under review because of the implausible expectations for rate cuts implied by the present positioning in US bonds and the psychological obsession with Fed policy in all asset markets worldwide.

US inflation accelerates to above 2.5% (<10%)

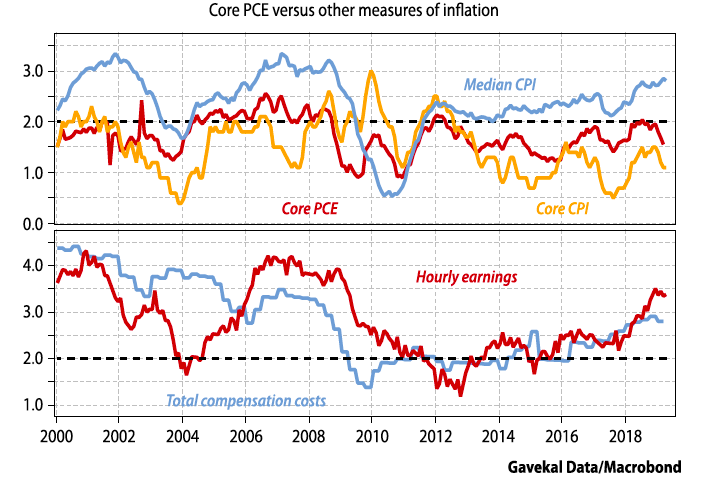

Another low probability risk, but one that would have a big impact, is US inflation. While several measures of prices and wages are gradually creeping upward as the US economy continues to enjoy full employment, aninflation upsurge serious enough to worry the Fed would probably require core PCE to jump above 2.5% and stay there for several months. That would be a major surprise. There has been absolutely no evidence in recent data of PCE inflation accelerating, even while wages, total compensation costs, gold prices and median consumer prices (see the chart over leaf), along with other traditional leading indicators of inflation, have been edging up.

As long as this situation persists, which it will partly because of the way core inflation is measured, the bond markets are likely remain relaxed about monetary tightening. And with no monetary tightening on the horizon, investors in equities, property and other risk assets will probably treat creeping inflation more as an opportunity for faster top-line growth, than as a threat to valuations.

Political risks

Trade wars: US-China, US-EU or EU-UK (25-50%)

Trade wars were a risk that seemed to be all but eliminated a few weeks ago. Now they have returned with a vengeance with Donald Trump’s escalation of anti-China tariffs. Since we have discussed at length the various scenarios for the US-China confrontation (see The Trade WarStory Lines Harden), I have only two points to add, with regard to market impacts. The bad news is that powerful voices in the Trump administration seem not to be content with a trade war against China, and are eager to wage war with Europe as well by imposing punitive tariffs on the autosector.

The somewhat better news is that the impact of tariffs and trade sanctions on financial markets and economic activity now looks less damaging than was feared last year. The fact is that China and the US have emerged largely unscathed from the tariffs imposed in the past 12 months, because supportive monetary, fiscal and credit policies in both countries have compensated for the hit to trade and business confidence. Meanwhile, some other emerging markets, especially in Asia, have already started to benefit from the partial relocation of global supply chains away from China. US and Asian financial markets may therefore be somewhat inoculated against further panic if the US-China dispute does seriously escalate. European markets, on the other hand, are likely to suffer much more from global trade conflicts as they did in 2018, if EU policymakers continue their tradition of tightening fiscal policy and bank regulation pro-cyclically whenever they see budget deficits expanding and credit conditions deteriorating because of weak export growth. On balance, therefore, trade policy now looks like the most serious political risk to the global expansion and the markets – with the main problem again concentrated in Europe, as it was last year.

Populist politics destabilizes the EU and euro (10 -25%)

The European Parliament elections on May 23-36 now look less likely to destabilize the EU and the euro than was generally expected a few months ago. While “populists” and other anti-integrationist parties look set to make some further gains, especially in France and Italy, the disruptive effects on EU institutions will be limited by two surprising factors.

Firstly, the political paralysis created in Britain by the Brexit saga has strongly discouraged all talk of secession among nationalists in other countries. If and when Brexit actually happens, this dynamic may change, assuming that the British economy continues to perform fairly well and political conditions return to normal. For the time being, however, Brexit is acting as a very effective deterrent to secessionists in othercountries.

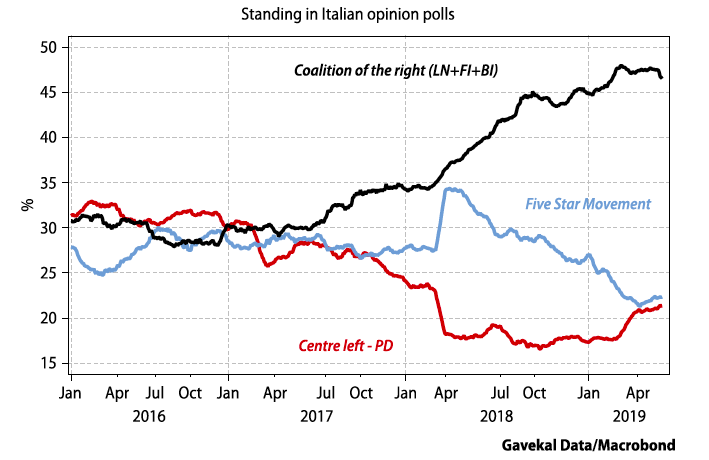

Secondly, political pressures inside countries where “populists” have already gained power are shifting these parties towards more conventional EU policies and away from disruptive nationalist positions. This shift towards more conventional politics has already been evident in Austria and Greece and also to some extent in Poland and Hungary. But Italy will be the most important test case. If this month’s European elections confirm the big swing expected in favour of the right-populist Lega at the expense of the left-populist Five Star Movement, a general election is likely to follow in the autumn. This will probably produce a more traditional center-right coalition government. This will still fight hard against pro-cyclical EU budget rules but will not pose an existential threat to the euro of the kind widely feared last year. Better still, success for Salving and his potential allies in the European elections could weaken the German-dominated austerity bias in the new European Commission and increase the likelihood of a suspension of the Maastricht budget rules, leading to the pan-European easing of fiscal policy that is the prime condition for an improvement in EU economic conditions and the euro’s long term survival.

US politics shifts from populist-right to populist-left (<10%)

As next year’s US election season approaches, some investors are already starting to worry about a sharp swing to the left in US politics, as suggested by the prominence of Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, as well as the recent fad for fringe economic concepts, such as Modern Monetary Theory and extreme versions of a Green New Deal. These are trends are certainly worth watching. But they are unlikely to have much impact on financial markets this year, if only because the field of Trump’s Democratic challengers is sowide.

As a result, it is hard to see how any clear leadership or coherent policies could emerge among the Democrats until the early US primaries in February and March next year. The most important caveat is that Trump could turn himself into a lame duck by committing some big strategic blunder, for example by over-playing his hand in the trade confrontation with China or Europe, or by bombing Iran and creating an oil shock, or by getting bogged down in a Venezuelancivilwar.

Political backlash against Big Tech monopolies (10-25%)

Political challenges to all the most successful tech companies seem inevitable in the coming years. Google, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon are still impressive technological innovators, but their profitability now depends on business models that mainly monetize monopoly rents and network effects. These businesses models could be challenged through special taxes, new forms of anti-trust enforcement, privacy laws, data protection or other forms of regulation. But one way or another the extraordinary profitability of these global monopolies will come under attack.

The monopoly risks are already partly reflected in fairly modest valuations for some of the Big Tech companies, although others are still trading on very high multiples that assume the current business models and profitability will prove sustainable. In any case, chipping away at Big Tech’s monopoly profits is likely to be a long, slow process, which is why I attach only a moderate probability to these adverse policy changes affecting stock market conditions in the next year or two.

Market valuation risks

Tech IPO bust hits venture & and private equity (10-25%) While long term political changes may threaten the profits of Big Tech monopolies, many smaller tech companies face a very different problem. They make no profits on their present business models, but investors value them on the assumption that they will ultimately achieve the global dominance of Google, Amazon and Facebook. For most tech stocks this is extremely unlikely. Very few operate in businesses with natural monopolies or network effects like Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon; or possess genuine technological or design leadership comparable to Apple. Investors have started questioning assumptions about global dominance and consequent profitability in the case of Tesla, Twitter and some smaller quoted tech companies.

But others that are equally unlikely to evolve into global monopolies are still valued as if they might evolve into the next Google or Facebook, even though Netflix, for example, is not really a tech business, but an entertainment producer. Many other mega-cap companies that are really quite traditional businesses, but are valued as future tech monopolies by private markets, are now queuing up for IPOs. The Lyft and Uber IPOs have already proved disappointing. These transport companies masquerading as tech businesses will be followed by Airbnb (a hotel booking service), WeWork (a commercial property financing and tenant-management business) and several finch companies that are not very different from credit-card businesses or banks.

If many of these IPOs disappoint, they could raise questions not just about the stock market valuations of mature tech stocks, but even more about the “hope value”attached by venture capital investors to what they see as future tech leaders. A de-rating in venture capital markets could become macro-economically significant in several US regions and if it spread to private equity valuations, which are also at nose-bleed levels, the impact could spread to financial markets more broadly and around theworld.

Autos and capital goods enter secular decline (10-25%)

The opposite end of the industry spectrum raises a different question of valuations that could prove even more macroeconomically significant. Are autos and the related machinery sectors now industries in secular decline? Will a perfect storm of new technology, environmental pressures and social changes mean that car manufacturers become in the early 21st century what steelmakers and shipbuilders were in late 20th century? These questions, like the ones about tech valuations, probably will not be convincingly answered in the next year or two. But they will need close monitoring, especially by investors in Europe and Germany, which are far more exposed to the auto and machinery sectors than other major economies, and could therefore face a bleak future of relative decline.

Article republished courtesy of Gavekal Research. Trials are available on the Gavekal site or by contacting sales@gavekal.com