It is well accepted that golf began on the linksland on the east coast of Scotland, played there at least since the 16th century. Once the railway age began, and holidays at the seaside became a possibility, towns such as St Andrew, Gullane and North Berwick developed into summer resorts. All of these towns had historic golf links and soon many Scots, as well as the more adventurous middle class English travellers, became acquainted with the royal and ancient game.

Golf took off much later in England than in Scotland. It was predominantly an inland game played in the major cities, large towns and even in small market towns throughout the country. But golf was also played at the coast. Linksland is not a Scottish preserve; it exists all around the English coast too, for example in Northumberland, Norfolk, Kent, Sussex, Devon and not least on the Wirral and the Lancashire coast between Liverpool and Blackpool.

The earliest coastal club to be established in England was Royal North Devon golf club at Westward Ho! in 1864. Other well-known clubs followed, such as Royal Liverpool at Hoylake (1869), West Lancashire at Blundellsands (1873), Felixstowe (1880), Royal Isle of Wight (1882), Lytham & St Annes (1886) and St George’s at Sandwich (1887). But none of these early links could be classified as seaside resort golf clubs. Their members typically consisted of local dignitaries as well as affluent gentlemen from the major cities. For example, the majority of the early members of Royal St George’s had London addresses and were probably also members of Royal Blackheath and Royal Wimbledon.

The seaside towns in England began to expand with the coming of the railways. The earliest and largest of these by far was Brighton which had a population of 100,000 by 1881, putting it amongst the 20 largest towns. Other parts of the country saw similar developments. Scarborough, originally a spa town, began to attract northern holidaymakers. The professional classes from Norwich fuelled the emergence of a resort at previously unfashionable Great Yarmouth. Bristolian merchants and their families made their way to Weymouth, Lyme Regis and Weston-Super-Mare. And, of course, Blackpool flourished with custom from Liverpool, Manchester and the Lancastrian textile towns.

What we now think of as traditional seaside entertainments began in the Victorian era, including itinerant musicians, minstrels, Punch & Judy, Aunt Sally stalls and donkey rides on the beach for children. Some sports also began to feature including archery, croquet, and bowls. And soon golf would join them.

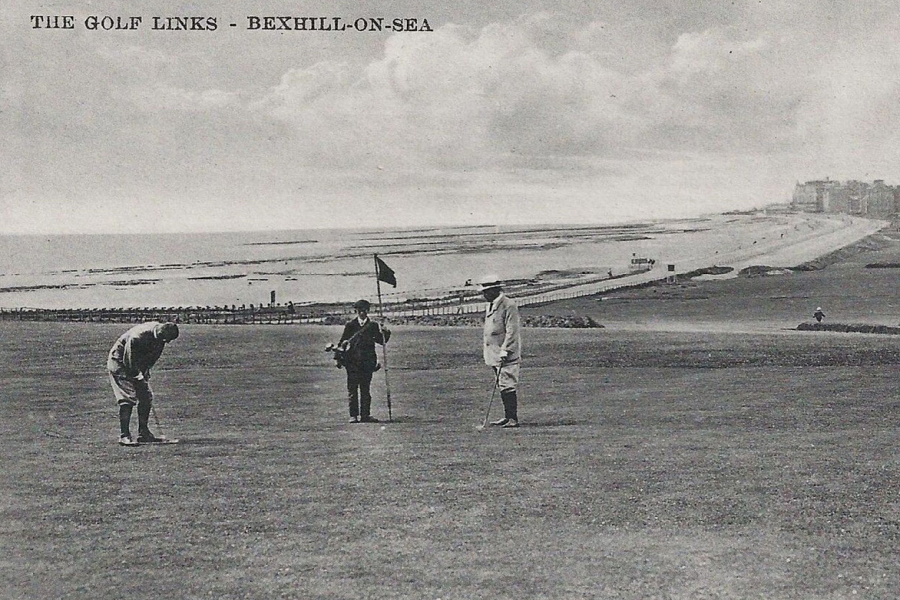

During the great boom in golf in England between 1890 and 1914, 184 golf clubs were formed at the coast, of which 144 were in traditional seaside towns largely catering for the influx of visitors during the summer months. Of the 100 largest resort towns in 1911, only two, Southsea and Teignmouth, did not have a golf club. It is clear that the opportunity to play golf became a core attraction for resorts, large and small, seeking to increase their appeal to day-trippers, summer visitors and retirees.

The golf clubs in the seaside towns were typically started by gentlemen from the professional classes – bank managers, architects, doctors and local businessmen. Civic leaders such as mayors, aldermen, councillors, and justices of the peace were also well-represented. An important initiative was to approach local landowners to explore the availability of a piece of ground where a course could be laid out. While not necessarily being golfers themselves, the landowners were typically enthusiastic to see golf clubs being formed in their locale. The land of interest to golfers was usually poor quality, sheep-grazing land, perhaps known locally as ‘the warren’ or ‘the burrows’ with a well-established population of rabbits. The landowners saw the benefits of a golf club, not only in drawing more visitors to the town but also as a means of encouraging higher quality housing development in the vicinity, thereby increasing the value of their estates. If an acceptable arrangement was reached, in almost all instances, the landowner was invited to become the golf club president, an honorary position solely entailing attendance at the annual prizegiving before an appreciative membership.

Not surprisingly, visitors were an important feature at the seaside clubs, typically accounting for about half their annual income. This was important in maintaining the quality of the courses and clubhouses, and it may also have enabled local members’ subscriptions to be partly subsidised, a business model that was not unappealing to the coastal retirees who had become golf’s latest devotees.