This article was originally published in March 2020.

This is the title of a Stereophonics song, but it also evokes yet another trend which Europe has sleepwalked into adopting from the US. Why, those subway trains covered from track to roof in graffiti have become synonymous with any self-respecting American movie, and a I read that a subway car was literally sprayed from end to end only this month in New York. Logistically at least, quite clever.

Those fascinating differences and values which once defined our continents have now brought about some curious homogeneity. Mindlessly or intelligently painting stuff is ubiquitous.

I look at graffiti and tattoos as the opposite end of the same spectrum: one is applied anonymously to property which doesn’t belong to us, and the other we have done to ourselves with full permission.

Both are very difficult to remove, and if I was asked today which would be a successful future business I would suggest tattoo removal as I can only see this being a huge future industry. Vogue is the prevailing fashion of the time and therefore by definition temporary!

Enough about tattoos; it’s graffiti I wanted to explore and try to understand its general acceptance.

Its origins are from the mid 19th century Italian, ‘graffio’ – ‘a scratch’ and was first manifested in the inscriptions found on rocks and walls in the ancient civilisations of southern Europe, north Africa and the middle-east.

Then it was used as a form of messaging and, although some of it apparently was often rude or offensive, we have chosen consider it charming over time – more through lack of understanding than anything else I imagine.

Graffiti’s current-day definition is: “….writing or drawings made on a wall or other surface, usually as a form of artistic expression, without permission and within public view”. I suppose the ‘public view’ part is crucial, or why bother doing it?

Carla H Krueger, author of psychological thrillers amongst other genres, has written: “Blank walls are a shared canvas and we’re all artists”

I am certainly no expert, but I understand there are at least eight different types of graffiti, ranging from genres such as ‘Blockbuster’ (large, often done with rollers); ‘Wildstyle’ (elaborate, esoteric); ‘Heaven’ (high level, out of reach, extra respect) and the boring old ‘Stencil’ (regarded as lazy). Tags provide a personalised signature for those in the know and I am led to believe it is disrespectful to write over another ’artist’s’ tag. Oh, the irony.

Carla H Krueger, author of psychological thrillers amongst other genres, has written: “Blank walls are a shared canvas and we’re all artists.” Likewise, Michael Ondaatje writes in ‘In The Skin of a Lion’, “Everyone has to scratch on walls somewhere or they go crazy”. It seems I am in the minority in my little societal cynicism and maybe I should just relax.

However, one aspect which goes unmentioned in this age of sustainability and waste is the huge cost of graffiti removal. This isn’t just private skin lasering of a heart or a nickname on the sad ending of an inked romance; it often involves chemicals, scaffolding and days of labour. In other words, it is a cost precipitated by an individual but borne by the public purse.

Now I’m aware I’m probably sounding a bit of a killjoy here (as opposed to ‘Kilroy was here’), and I wonder if my reaction is in part due to my vocation. As an architect who works hard for the closest one can realistically hope to achieve to constructed perfection, I have to be honest and say graffiti jars with me.

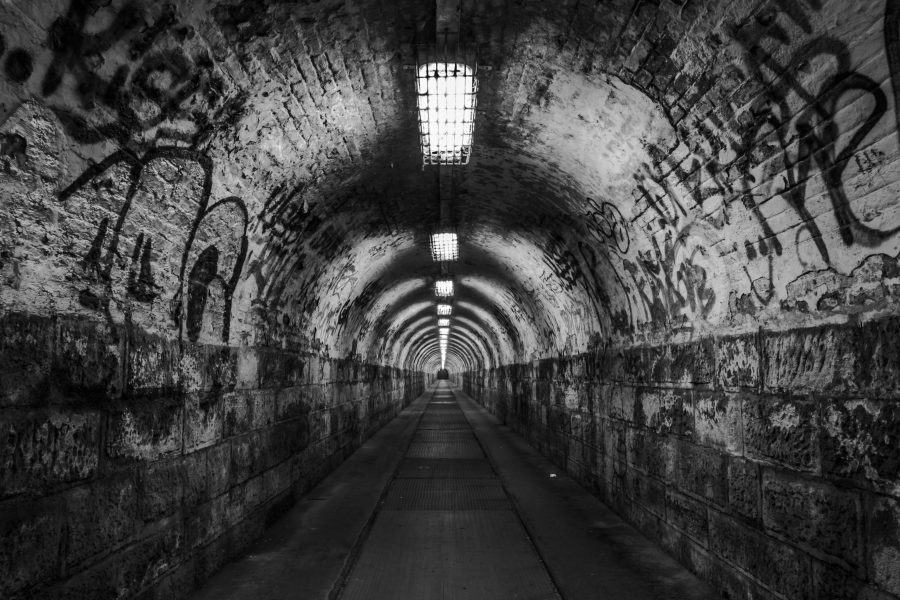

It’s not just buildings and trains which attract what is officially categorised as vandalism: subways, substations and bridges are targets too. The lengths and degrees of daring with which some people are prepared to go with their spray cans are clearly part of the badge of honour!

Sadly, I just don’t buy vandalism as an art form. Call me old-fashioned, but taking a spray can to someone else’s property just doesn’t sit well with me. I think it’s linked to wider societal issues and something to do with pride in one’s community. I once designed a building with a 2 metre high white rendered wall onto the street; I joked that I should design a nice stainless steel spray can holder as it was such an inviting blank canvas.

The thing is, the building became a welcome friend in the locality and twenty years on it has never been defaced (…until this is published!) There are lots of examples where this is the case – where people recognise someone else’s endeavours to design something of quality in their local environment. Perhaps this explains why anonymous ‘artists’ often choose anonymous structures for their work? No-one individual gets hurt; it’s the state which takes a bashing.

So, where does graffiti end and street art begin? Street art is usually political and used to notorious effect by the prolific yet anonymous Banksy and his follower of fakers in places like Brick Lane, Bristol and Bethlehem. I have witnessed the latter installations first hand and in that context it is powerful stuff.

But I can’t attest whether his subsequent ‘Walled Off Hotel’ shares this poignancy as I haven’t been there. There always seem to be protracted discussions reported in the media involving owners and local authorities as to the retention of Banksy’s work in this country (nearly as protracted as the Oxford shark-through-the-roof debate).

Nowadays, the walls themselves are often removed to a new home with his work still attached, rather than destroy what has become

As I write this, I feel as though what started out as a fairly superficial commentary limited to a few hundred words has further to go, deeper to dig. I am surprised graffiti doesn’t attract more conversation given its influence on the world. Perhaps it’s just me.

As an aside, the song ends rather tragically. It’s not Shakespeare but it is quite poignant:

“…Train comes the coach she’s always used to

The doors read a “Marry me I love you”

Heart stops ecstatic and suspicious

She makes the call but he don’t pick the phone up

The train sped down the line

It was last train he would ride oh no…”