On 20 January 2021 the Czech lower house of parliament passed a bipartisan bill that, if enacted, would potentially pose a significant threat to one of the EU’s core elements, its single market with 450 million consumers.

If approved in the upper house and by the Czech president, the bill would require retail establishments with more than 400 sq. m of retail space to carry at least 55% local produce such as meat, vegetable and fruits if they are domestically available, starting in 2022. The minimum quota would reach 73% by 2028.

Similar proposals are being discussed in Bulgaria, Romania and other countries, especially since covid highlighted the fragility of cross-border supply chains.

Why does this matter?

Well, when thinking about markets it’s helpful to recall Gordon Gekko’s words in “Wall Street”: “The point is, ladies and gentlemen, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge – has marked the upward surge of mankind, and greed – you mark my words – will [save] that other malfunctioning corporation called the USA. Thank you.”

The EU Commission’s instinctive reaction to the bill was to question what ulterior motives the Czech president Andrej Babiš might have. This suggestion relates to Mr Babiš’s purported conflict of interest with respect to Agrofert, the biggest Czech agro-industrial conglomerate, which he founded and allegedly still controls.

Looking at Agrofert’s product portfolio, which is focused on meat, dairy and pastry products, this argument is not that far-fetched. However, due to Agrofert’s food industry investments in Germany, the company is likely to experience negative impacts as well.

Let’s look a little further, follow the money and see who’s crying wolf.

In early December 2020 ambassadors from eight EU countries, including Germany and Poland, sent a ‘confidential’ letter to EU MPs arguing the bill posed a threat to the EU’s single market.

Using this political blitz as an indicator, let’s start by looking at the structure of Czechia’s food imports and its main conduit, food retailers.

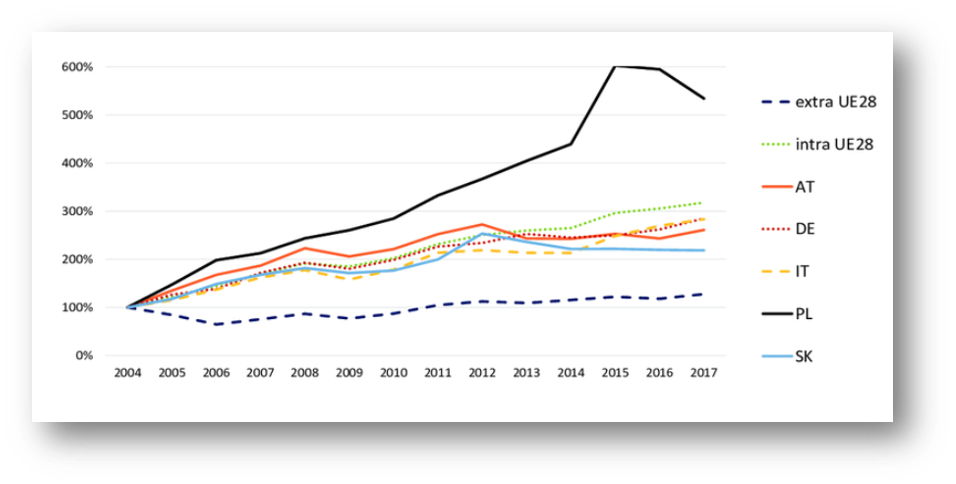

Structurally, agri-food sourced from Poland, Germany and Italy saw the biggest relative increase in Czech shopping baskets since joining the EU’s single market in May 2004, along with Poland and a number of other CEE countries.

Czech agri-food imports by source

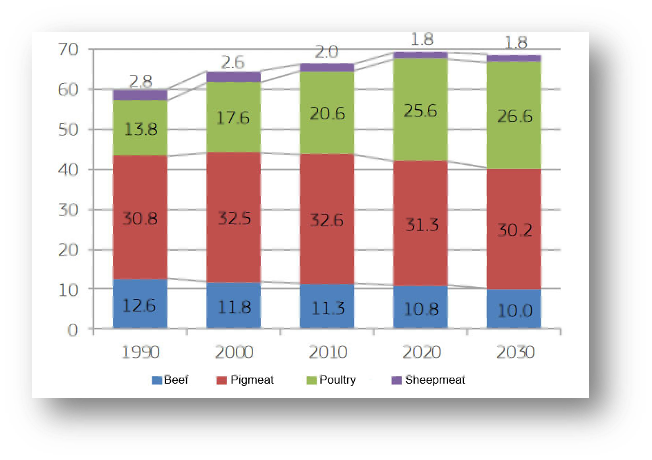

Given its high-value shopping basket characteristics, let’s use meat imports as a proxy to discuss cross-border agri-food trade. The main meat categories consumed in the EU are pork and poultry, with 31.3kg/capita (45%) and 25.6kg/capita (37%) respectively (see further stats below).

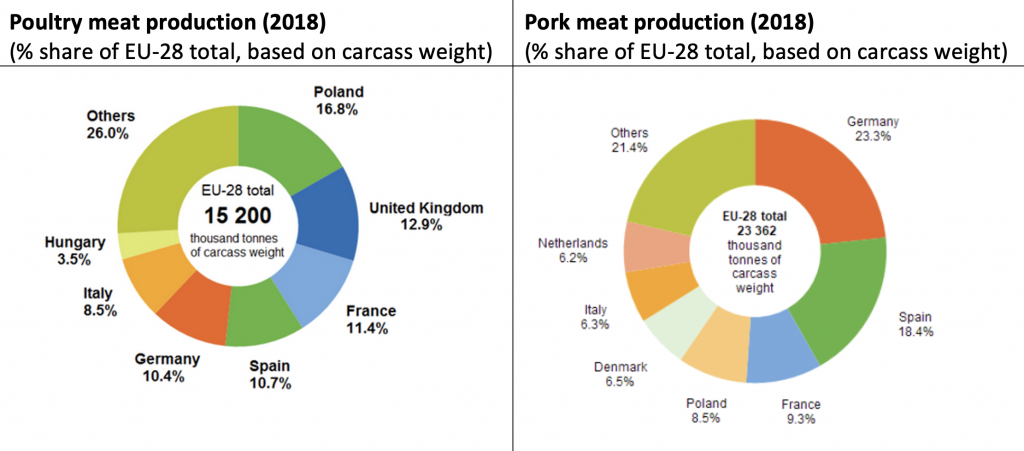

Due to space restrictions in western Europe and helped by generous EU agriculture subsidies, CEE countries became the preferred investment targets for meat agri-food investors since 2004. The focus for Poland became large-scale poultry production, which boosted its poultry meat exports within and beyond the EU.

By 2018 more than one-sixth of the EU’s poultry production was based in Poland. With the UK having left the EU in December 2020, this concentration is likely to increase significantly. Shifting consumer preferences (more chicken, less pork and beef) provide an additional boost.

Germany produces almost one-quarter of every kilogram of pork consumed within the EU.

Hence both Poland and Germany, along with Spain and France as major EU meat producers, have a strong financial incentive in keeping the EU’s single (food) market accessible.

Poultry production

Chicken run – EU meat consumption (kg/capita)

How about food retailing in Czechia?

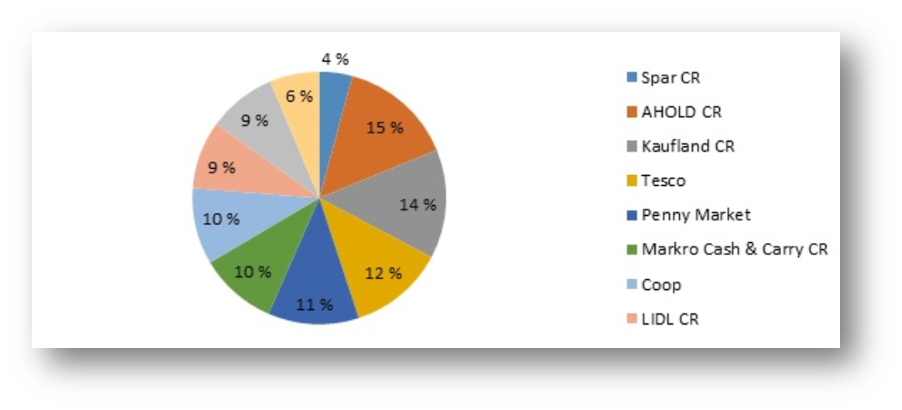

Lidl, Kaufland (Lidl-Schwarz Group), Spar and Penny (Rewe Group), Makro C&C (Metro Group) are all headquartered in Germany, with significant political clout, given their home-market scale and labour market impact.

With a 2015 market share of 48% (likely to be beyond 50% by now) in Czechia, they exert significant market control and as such need to protect their volume-oriented supply chains within the single European agri-food market.

Czechia – food retail market share (2015)

Apart from the retail market concentration and related financial incentives, another important aspect comes into play which makes the free movement of agri-food products across a barrier-free single European market so essential for large retail chains: private labelling.

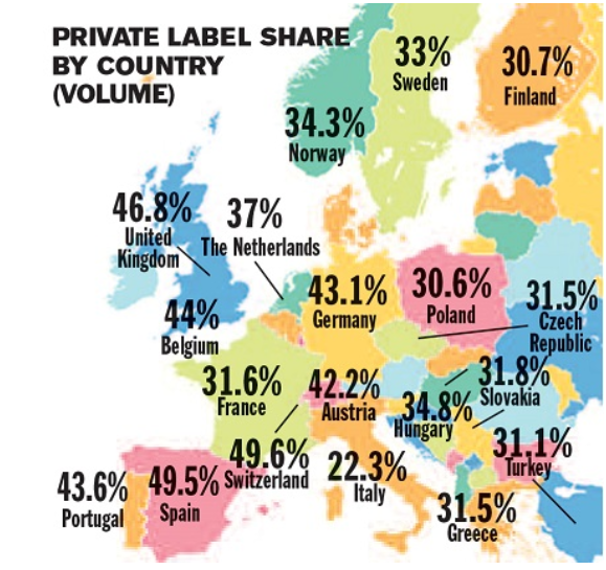

As every grocery shopper probably has experienced over the past couple of years, branded products, especially in food retailing and drugstore products, face increasing shelf-competition from private label products, i.e. retailer-owned product ranges competing with branded third-party products. With significant replacement potential, these products have achieved a 31.5% market share in Czechia and an even higher proportion in most western European markets.

Now, in order to benefit from economies of scale, retailers typically have these private label products manufactured in large quantities, often in their main home market, and then shipped cross-border to their respective retail outlets.

Not being able to use this scaling advantage (due to market access restrictions such as those in Czechia) would severely disrupt their business model and diminish often razor-thin margins in a cut-throat market.

Where does this leave us?

Well, it’s not that complicated. The shadow fight over (food) market access is merely a pressure point in a much larger discussion about the ongoing EU-budget negotiations for 2021-27.

Why? Apart from broad-based regional development and cohesion expenditures (€380.1bn) the biggest budget position relates to Common Agriculture Policies (CAP) with a volume of €354.1bn for the seven-year budget cycle. These farm subsidies, which once made up more than 60% of the EU’s budget, today stand at only 30% with a decreasing trajectory.

By (credibly) threatening to severely limit access to its domestic agri-food market, Czechia is essentially asking for a top-up on its CAP allocation in order to keep local farmers and agri-food producers happy.

What’s at stake?

Apart from safeguarding the single European market –a core element of a rather fragile post-Brexit/post-covid EU – and to avoid setting a precedent for others, let’s retreat to one of Brussels’ back rooms, grab a good 12% Belgian Bush beer and do some maths.

The Czech retail market for food, beverages and tobacco has an annual volume of €1.4bn. The EU’s proposed 2021-27 budget allocates €7.7bn, i.e. €1.1bn a year in farm subsidies (CAP) to Czechia. Topping that number up to €1.4bn a year to get it on par with the retail volume could potentially be a way to resolve this situation. With an eye on Germany’s €41bn and Poland’s €30.5bn in CAP allocations, this idea may have crossed the mind of a few politicians in Prague when voting ‘ano’ (yes) to the bill.

“The point is, ladies and gentlemen, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good. […] Greed – you mark my words – will [save] that other malfunctioning corporation called [the European Union]. Thank you.”