In a new four-part series, David Shiers looks at how the design of the built environment has evolved to take account of ‘Green’ issues and considers what may lie ahead in the way we experience the buildings in which we live and work.

With literally hundreds of thousands of low environmental impact buildings now in existence worldwide and ‘Green’ buildings the new-build norm in the UK, it’s easy to forget that just 30 years ago, it would have been hard to find more than a handful of them in any one country. We only see Green buildings beginning to be developed more widely from the late 1960s onwards in Earth or Straw Bale houses, in the buildings of the counter culture and in prototypes such as the Bateson Building in the USA.

The Bateson Building 1977, Sacramento, California. Note the external solar shading to reduce the cooling load on the building’s environmental services.

The ideas of the early environmental visionaries such as Cerda (b.1815), Howard (b.1850), Geddes (b.1854) and Buckminster Fuller (b.1895), whilst influential in Town Planning and architectural circles, were not universally adopted. Governments and mainstream property professionals require the necessary incentives and drivers to embrace change and it took time to understand and accept the importance, feasibility and potential advantages of a Greener approach to building projects. Even in academia, study of the relationship between property and the environment only began in earnest in the recent past. In 1995, in the department of Real Estate at Oxford Brookes, we were the first surveying course in the UK to introduce modules which dealt specifically with Green buildings and the learning curve was steep for teaching staff and students alike.

It could be said that it is historic, vernacular architecture which provides the earliest examples of Green building; that the ancient mudbrick Pueblo buildings of North and Central America and the medieval timber frame, wattle and daub, cob and thatch structures of northern Europe are as Green as it gets. This is largely true of course – and many lessons on materials use and thermal efficiency have been learnt from such buildings. Here though, we will discuss projects in industrialised societies of the past 150 years where the adoption of a Green approach was taken as an informed decision; where a choice was made between ‘Green’ and the more conventional or ‘Brown’ solutions available at the time.

The historic examples of buildings which inspired and informed our current Greener approach to design are characterised, to varying degrees, by features such as:

- the prioritisation of the health, well-being and comfort of the building’s users

- ensuring easy occupier access to open and/or green space and good quality public realm

- efficient energy generation and use

- reclaimed, low environmental impact, efficiently produced and transported materials

- good waste management

- connectivity and access to effective transport systems

- minimisation of land, water and atmospheric contamination.

These are of course, recurring and enduring environmental themes and form the basis of many of our current Green badging systems such as BREEAM. However, most environmentally responsible projects pre-1990 address only one or two of these issues and even then, sometimes only partially. However, allowances must be made for what was at the time, often high-risk, innovative work; limited by the technologies of the day. Even in modern Green buildings, whilst the benefits of say, better internal air quality are generally acknowledged, some projects are criticised for requiring too great an input from occupiers in managing their ‘natural’, sometimes slow-to-respond, environmental systems. Improving the quality and occupier experience of all buildings is ongoing work in progress.

Some of the principles underpinning modern Green architecture and Town Planning can be seen in the work of Ildefons Cerda in Barcelona and in Ebenezer Howard’s ideas for the Garden City. Both men sought to improve human health in the 19th century city but were also driven by a sense of social justice to promote a more communal, cooperative, fairer world. It is no coincidence that in the UK in the 1990s, some of the early adopters of the principles of Green building were the cooperative banks and Mutuals (the Prudential’s Property Fund Managers for example). Many of these organisations had been founded by Quaker families in the 19th century and had not only a fiduciary duty to their stakeholders but also felt a moral obligation to improve society. In Cerda’s plans for a series of new urban apartment blocks in the Eixample area of Barcelona, developed from 1860; the buildings were arranged around an open central space of natural light and breezes for cross-ventilation and cooling. All had good sanitation with underground infrastructure and at street level, vehicles were intended to be separated from outdoor social spaces.

The Eixample area of Barcelona. Cerda had originally intended the heights of the blocks to be limited, for the ends of the squares to be open and for each apartment to benefit from sunlight and good ventilation.

In Howard’s Garden Cities, efficient transport networks, connectivity between work, leisure and home, clean air and the relationship between nature and the built environment are key features. The exponents of Howard’s ideas (e.g. by Unwin and Parker at Letchworth, 1904) also tended to use traditional housing forms and materials rather than more mass-produced systems. Howard’s ideas on minimising the citizen’s exposure to atmospheric pollution, the importance a ‘Green Belt’ around urban areas and the importance of creating urban farms remain current.

As well as being a progressive thinker and Town Planner, Patrick Geddes was a sociologist, geographer, and biologist. He was also a Fabian socialist and considered that good physical health and domestic stability was necessary for an individual to thrive, develop and participate in society. Geddes’ Masterplan for the White City of Tel Aviv was developed between 1930 and 1950 with streets running west to east to catch the sea breezes and individual buildings designed to respond to the micro-climate of the site and their position on it.

The White City, Tel Aviv in 1940

Tel Aviv was no Garden City however and the scheme was a diverse, Modernist conurbation developed by different architects working within Geddes’ Masterplan. Also, in a far-sighted critique of what we now refer to as ‘professional silos’, Geddes thought that in his modern world, there was too great a focus on a single specialisms and that this risked fracturing the obvious connections between them. In foreseeing the advantages of today’s more interdisciplinary approach, he felt it essential that geography, anthropology and market economics were seen as the pillars of society and that sociology should be developed as a science of “man’s interaction with a natural environment…and the improvement of town planning; the chief practical application of sociology.”

It is interesting and significant that another 20th century pioneer of Green ideas, the American Richard Buckminster Fuller was also influenced by strong moral, political and Unitarian religious values. Fuller was an early advocate of doing more with less; the efficient use of energy and materials from renewable sources and the recycling of low-value and waste materials into lightweight, high-value, more easily transportable components. His domes and lightweight prefabricated structures influenced the designs of Archigram which in turn had an impact on the high-tech architecture of Norman Foster and Richard Rogers.

Buckminster Fuller’s Montreal Biosphere, 1967.

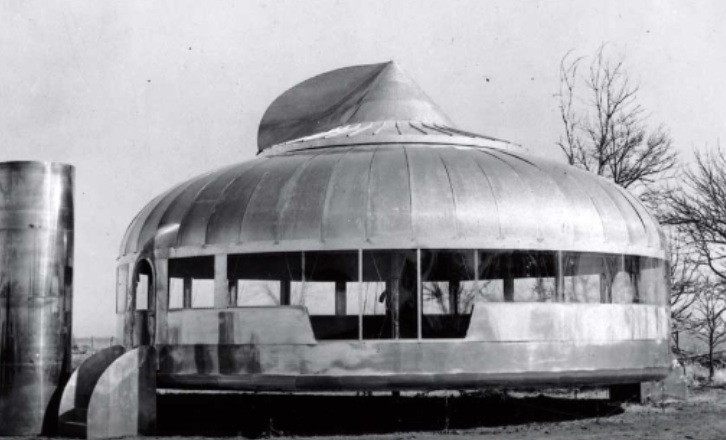

Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House. Conceived in the 1920s – built and developed in the 1940s as a prefabricated kit house which was energy efficient, easy to transport and used materials which were claimed to have a low environmental impact. It also offered reduced water consumption and used the rotating ventilator cowl on the roof to capture natural winds for cooling and air circulation.

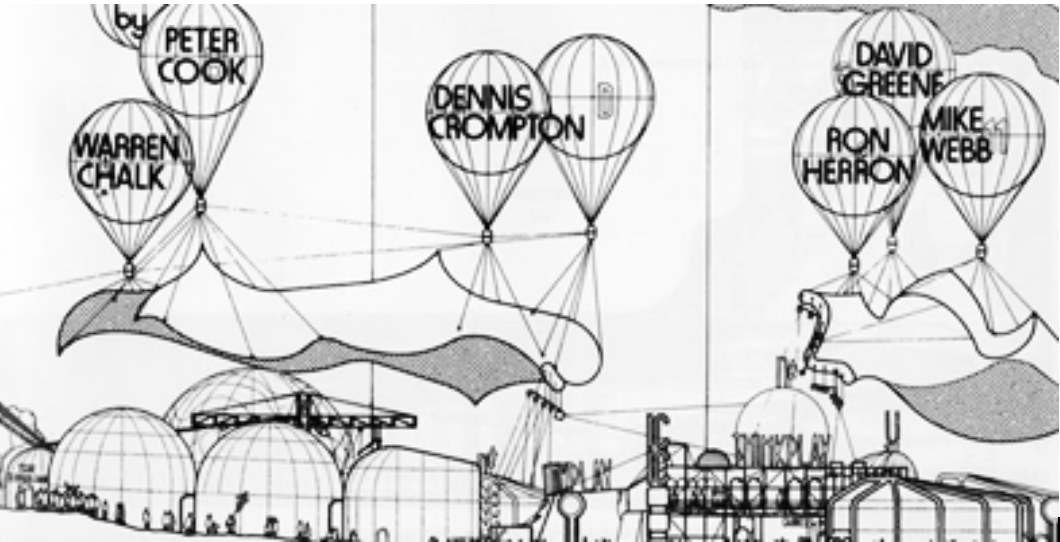

Archigram – Floating City concept, 1970. Demountable, pop-up, low environmental impact solutions complete with pop-art themes from the 1960s.

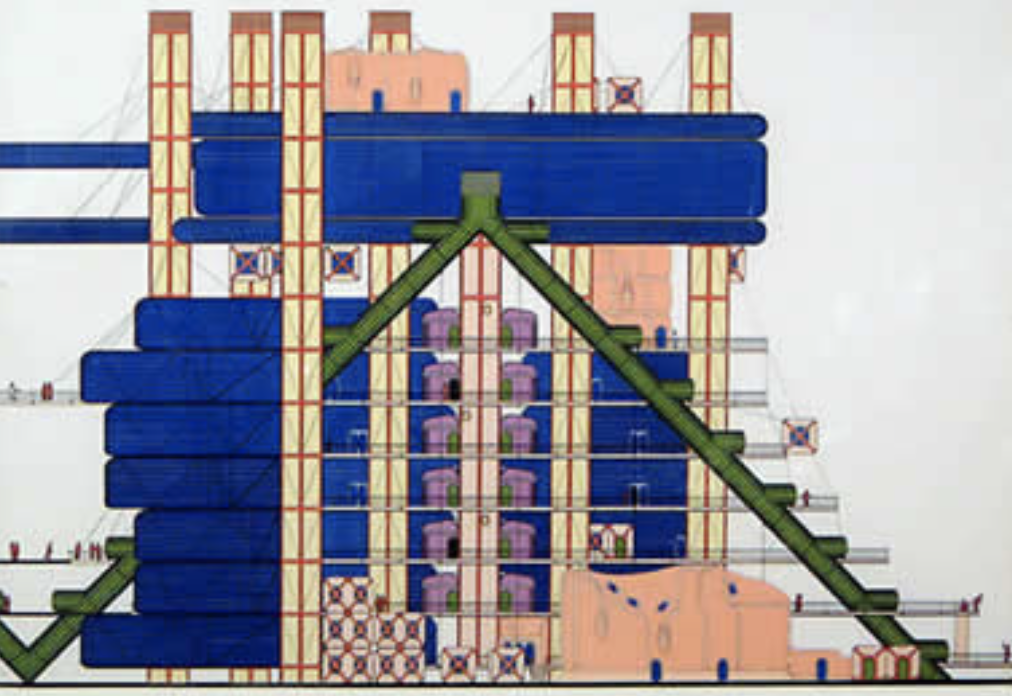

Archigram – Plug-in City. 1964. Detachable, energy efficient pods reminiscent of the later Lloyds building by Richard Rogers.

Norman Foster’s 1975 Willis Faber building is not usually regarded as a Green building but a closer look reveals a green roof, interiors filled with natural light and a high level of amenity for the occupiers; all features of the Green buildings of today.

Willis Faber Building, Ipswich UK. Open, informal, democratic spaces; a marked contrast to the dreary, punishment block environments of many office buildings in the 1970s.

By the time the Bateson building is constructed in 1977, most of today’s environmental parameters and the techniques used to achieve them are in place. It is a seminal project; anticipating the form and features of many future green commercial buildings in acknowledging the concern with energy efficiency following the 1973 oil crisis.

The Bateson Building designed by Sim van der Ryn. Note the large, naturally lit atrium space and one of the vertical tubes used for air recirculation.

In 1973, virtually overnight, energy became a very expensive commodity for oil-dependent industrialised countries. In the UK and elsewhere, new Building Regulations and Codes of Practice were quickly introduced to ensure greater energy efficiency in all building types. Within the environmental movement, the established concerns for human health and the responsibility to protect the natural world were added to, and given fresh impetus by, a new and powerful economic driver. The convergence of these three push-pull factors provided the beginnings of a business case for environmentalism which could be used to change the property sector and indeed, society as a whole. In the 1970s, the three pillars of sustainability – social, environmental and economic; came together for the first time to give momentum to the then still embryonic Green building movement.

Photo credits and Bibliography

http://www.greatbuildings.com/buildings/Bateson_Building.html

http://www.spatialagency.net/database/buckminster.fuller

Fuller photo: Cédric THÉVENET https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buckminster_Fuller#/media/File:Biosph%C3%A8re_Montr%C3%A9al.jpg

By Rmhermen at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons., GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1917827

Southern Orientation and Natural Cross Ventilation: Mind the Gap(s); What Clients, Valuers, Realtors and Architects Believe. A Qualitative Approach – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/Aerial-of-part-of-Eixample-Barcelona-and-typical-block-Cerda-intended-to-maximize-solar_fig4_321110085 [accessed 29 Aug, 2018]

Tel Aviv: תכנון ובניה בישראל, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11011690

http://www.archigram.net/projects_pages/plug_in_city.html

Photo of Willis Faber interior by Foster & partners

Lehmann, S. ‘Green Urbanism: Formulating a Series of Holistic Principles’, S.A.P.I.EN.S [Online], 3.2 | 2010, Online since 12 October 2010, connection on 19 August 2018. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/1057

Keeping, M. & Shiers, D. 2017, Sustainable Building Design, Wiley Blackwell pp180. ISBN 978-0-470-67235-8

Munshi, Indra (2000): Patrick Geddes: Sociologist, Environmentalist and Town Planner in Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 35, no. 6 (5-11 Feb. 2000) p. 485-491

Geddes, Patrick. ‘Sociology as Civics’ in Philip Abrams, The Origins of British Sociology, University of Chicago Press 1968.

Halliday, R J (1968): “The Sociological Movement, The Sociological Society and the Genesis of Academic Sociology in Britain”, The Sociological Review, Vol 16, No 3, NS, November.

Marks, R.W. (2018) https://www.britannica.com/biography/R-Buckminster-Fuller;

Cerda sources: https://web.archive.org/web/20100619105757/http://www.barcelonametropolis.cat/en/page.asp?id=33&tagId=166