On 11 May, the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee raised Bank Rate to 4.5%, a level last observed in October 2008. Since November last year, the Bank has also been reversing its asset purchase programme, reducing the size of the portfolio by about £33bn over the past 6 months. While the committee’s rhetoric continues to be quite aggressive in terms of the need for further tightening measures, in the context of stubbornly high consumer price inflation, quantitative measures of money and credit suggest that painful times lie ahead. Has the Bank misjudged its policy actions yet again?

Every month the Bank of England publishes its Bankstats tables, a motley compilation of money, banking and credit data that sheds light on the shifts in UK borrowing and deposit-holding behaviour by type and sector. These have long since ceased to attract the attention of the mainstream media and very few economists pay heed to them. Yet, over recent months, Bankstats have been sending a clear message of money and credit deceleration, which is all the more compelling when considered in inflation-adjusted terms.

The haemorrhaging of deposits from the US banking system, particularly the smaller regional banks, has been gaining coverage and concern for more than a year, but there are echoes in the recent UK data. In 5 of the past 6 months, the stock of broad money (M4 excluding some erratic financial intermediation categories) has fallen. The annual growth rate has dropped from 5.5% in March 2022 to 1.4% in March 2023. Within the aggregate, household deposit growth has fallen from 4.6% to 2.6%, private non-financial companies’ deposit growth, from 5.3% to -3.3%, and that of other financials, from 7.2% to -2.4%. Simply put, the interest rates banks have offered on deposits have lagged well behind the increases in Bank Rate and (mainly) corporate money has moved. There are better options.

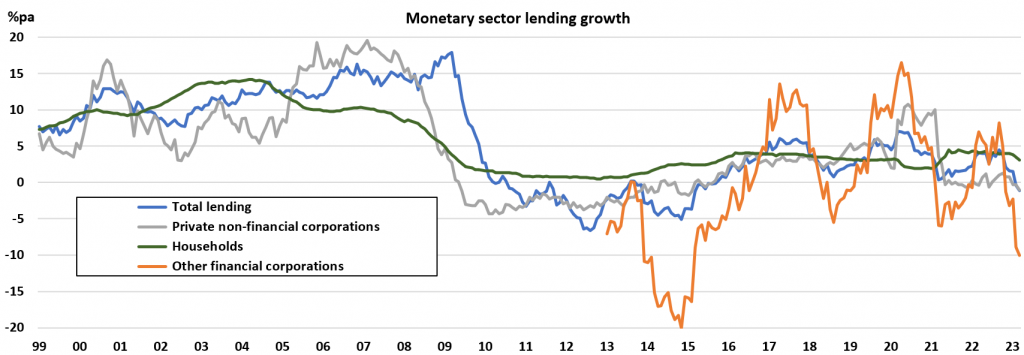

If banks were confident in the economic and financial outlook, they would expand their net lending and, by virtue of double-entry book-keeping, their deposits would revive automatically. In fact, the opposite is happening; banks are trimming their lending, especially to the financial sector. In Figure 1, the sector profiles of lending growth in 2023 are beginning to resemble those of 2020, as the pandemic was unfolding. Credit conditions are tightening in terms of availability as well as cost. This combination has a reliable track record in dampening demand and tipping overall economic activity into recessionary territory.

It is well known that the tightening of monetary conditions operates with a lag. The greatest cumulative impact of higher borrowing rates and the tightening of lending conditions has yet to be seen. Moreover, the freezing of the higher rate tax band in April has carried hundreds of thousands of taxpayers above the 40% tax threshold. Disappointing retail sales data for March has been blamed on the weather, but that does not explain why non-store sales volumes are still 10 per cent lower than a year ago. The noose around the neck of UK households is still tightening. Consumer services expenditures rebounded impressively last year, but these are also likely to fade as 2023 wears on. Our recession forecast remains.

Source: Bank of England

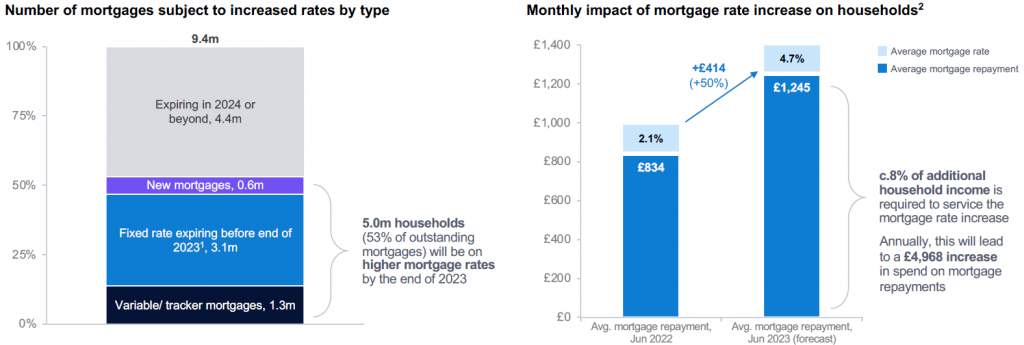

According to Teneo, the average mortgage rate paid in June 2022 was 2.1 per cent; this is forecast to rise to 4.7 per cent in June 2023 (Figure 2). Teneo estimates that mortgage payments will absorb an additional 8 per cent of household income in June as compared to a year ago. Already, we observe household food and drink, alcohol and tobacco, and household goods and services in rapid retreat. The compensating surges in transport, recreation and culture, restaurants and hotels last year contained an element of pent-up demand released in the aftermath of Covid. These discretionary items are liable to feel the budgetary pinch in the second half of 2023.

Source: Bank of England

The UK bears the hallmarks of a supply-constrained economy. Despite the post-Covid surge in demand, aided and abetted by bloated public expenditure, output in most sectors of the domestic economy is flatlining or worse. The external balance moved much deeper into deficit last year as imports plugged the gap. The UK has one of the highest inflation rates in Europe, and only partly because the effective rate of energy subsidy has been lower. Corporate profitability remains buoyant, with double-digit profit gains across large and small businesses last year, but the prospective return on capital is falling. Goods inventory to sales ratios have moved higher.

It is possible that policymakers are being duped by still-buoyant labour market statistics. Although the unemployment rate has edged up from 3.6% in July– September 2022 to 3.9% in January–March 2023, employment growth remains strong and there remain more than a million unfilled vacancies. Perhaps, it is thought that higher interest rates will help to persuade groups of workers to settle for smaller pay increases. For whatever reason, the Bank’s MPC appears oblivious to the clear and present risk that it has already adopted a policy stance that is overly restrictive. Welcome to USB (until something breaks) policymaking!