Property as safe haven in downturn.

As I reach the officially designated twilight years of my career, the recent burst of inflation in the UK and the upward shift in bond yields brought memories of my early days, emerging into the world of work with inflation at 15%, the bank base rate well above 10% and 10-year gilt yields at around 13%. This time, amid the market and political turmoil, the social media seemed full of people of my generation reminding the succeeding generations how tough it had been for us, how we had survived it and that they should stop moaning (and that we’d told them this would happen all along). What struck me forcibly was how distorted and false many of those memories were, how much they underplayed the personal suffering that many experienced, and how little they seemed to grasp the nuances and complexities of the economics then and now, failing to account for the technical, economic and social changes that affect outcomes.

Well, that’s social media and nuance isn’t a key feature of the digital world. Yet in real estate, we see similar oversimplification in commentaries. Bold, strong statements make for better press releases and soundbites, of course, and are intended to give an impression of confidence and reassurance in an uncertain market. My worry, though, is that they become received wisdom, particularly when made by established industry opinion formers and market gurus.

I will focus on ‘property is an inflation hedge’. How many times have we heard that over recent months, in professional and retail markets? How often is it questioned or analysed critically? It has become an act of faith or a mythology, something which may have elements of truth, but is believed for reasons that are nothing to do with truth. Let’s explore the realities behind that, focusing on commercial real estate, then ask why it remains received wisdom.

“Average returns on property are higher than inflation, so it’s a hedge! What else is there to discuss?”

We should probably start with a definition of hedging. Early in my career, I recall a major institutional investor berating academic discussions on inflation along the lines of, ”Average returns on property are higher than inflation, so it’s a hedge! What else is there to discuss?” Technically, we mean that changes to the returns should move directly in line with changes to our measure of inflation – it isn’t enough to beat inflation on average. It is the matching of performance that is important (as the pension/LDI panic of September showed). We need further definitions too: is that return total return, income return, or rental growth and capital appreciation? When we discuss inflation, should we separate out anticipated inflation and inflation shocks? These definitions are important and lead to different results which differ across types of real estate.

We know some stylised facts from research examining the relationship between real estate returns and inflation. The first – one that the industry resists – is that very long-term real growth in per square metre capital values and rents is close to zero (particularly when costs are properly accounted). This might seem counter-intuitive: surely real estate should capture underlying real economic growth? This, though, ignores supply-side adjustment. Even with lengthy lags and planning restrictions, supply tends to match demand long term (office floor space and financial employment in the City of London have very similar average growth trajectories). Redevelopment can increase the density of land use; thus land value will tend to capture economic growth, not the rent or value per unit of space (and hence not the existing building). Investors rushing into logistics or the current favoured ‘alternatives’ sector should carefully assess longer-term supply side adjustment in investment evaluations.

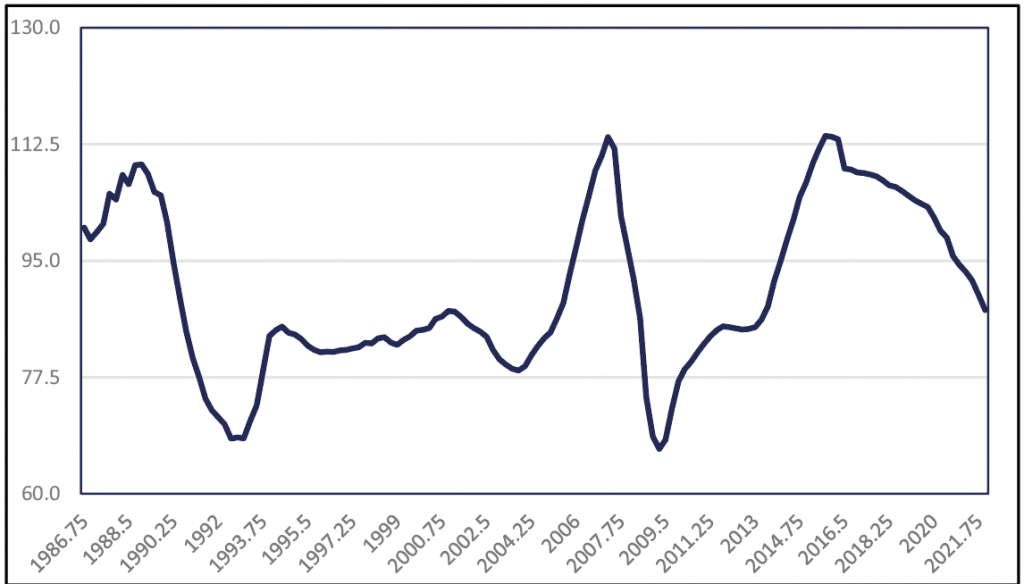

UK office market real capital values 1986-2022

The second fact is that, while commercial returns are a (somewhat weak) hedge for expected inflation, they are a poor hedge for unanticipated inflation shocks. The underlying rationale for real estate to be a hedge is that the rent captures a share of the tenant’s business activity and that turnover increases with inflation – hence so, too, should the rent. But for rents to adjust, we need a new lease or rent review. UK rents are typically fixed for five years: any inflation shock (by definition not anticipated by landlord or tenant – if they did, it wouldn’t be a shock) occurring between letting and review cannot be reflected in the rent passing. At review, there may be adjustments reflecting the inflationary trajectory and for larger investors, there may be portfolio effects as some leases review each year.

The third fact we need to consider is market, central bank and Government reaction to inflation. Conventionally, the central bank will increase short interest rates. Longer-term rates will be influenced by that, and by exchange rate and bond market impacts as international parity relationships remove arbitrage opportunities. As the brief Truss-Kwarteng ‘experiment’ showed, small open economies cannot isolate themselves from broad global forces. In turn, interest rate movements affect real estate capital value (through a discount rate channel) and income potential (through the impacts on overall economic activity). A further complication is the source of inflation: commodity and monetary-driven inflation may have very different impacts to that coming from underlying real demand growth.

Finally, it is important to think about social and technological change, and its differential impact on sectors and on places. The obvious example here is retail. Retail rents might be expected to hedge inflation, since retailers’ turnover is linked to sale of goods in nominal, inflated prices and rent should track turnover. In aggregate, though, this assumes that sales take place in shops. Increasingly, they do not. The pandemic made this stark, but it has been a trend in plain sight for many years. Was it reflected in the yields that investors were prepared to pay for retail? Was the implied rental growth (both nominal and real) plausible given the technological shifts occurring? Did required returns provide appropriate risk premia? Almost certainly no. While the retail example is much discussed, it illustrates a general principle: the inflation-hedging properties of an individual building, sector or market can easily be eroded by the process of change.

So, we really cannot say with confidence that commercial real estate reliably hedges inflation in any technical sense, beyond a weak tendency for long-run prices, rents (and costs) to follow inflation – a relationship that can be disrupted for individual markets and sectors. So why do we keep hearing it?

Is it because it ‘sounds like common sense’ and the analysis goes no deeper than that? That the industry has no real tradition of back-testing forecasts or investment decisions? Is it that a ‘people’ industry tends to scorn complex analyses or nuanced discussions in favour of bold, definitive displays of certainty whether or not they are grounded in reality? I suspect that this last point is an important one, aided by a tendency to lionise charismatic leaders whose pronouncements take on a reality of their own, immune to counter-evidence. That, and the behavioural factors that characterise investment processes in real estate, is something I’d be keen to explore further as I enter my vintage years as a researcher.