Comparing economies is an inexact science.

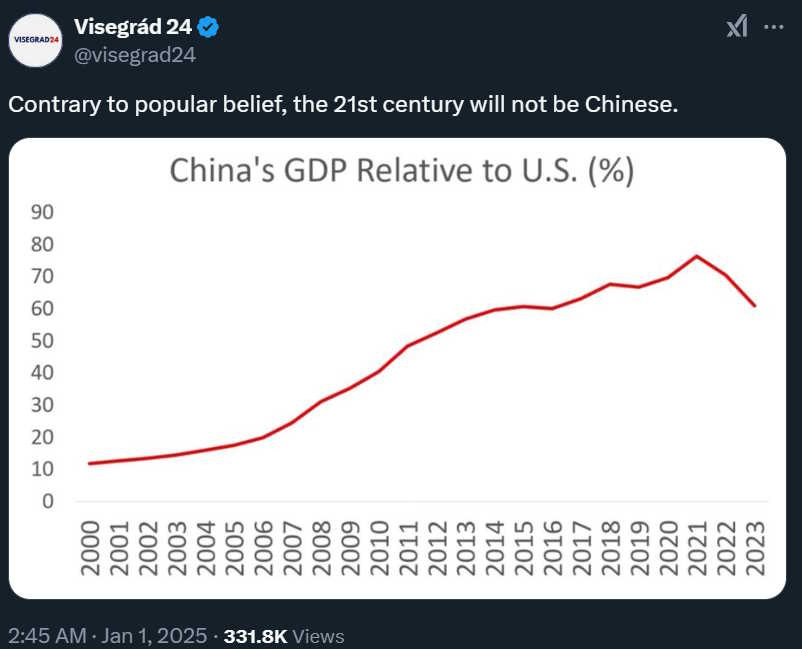

Comparing the size of countries’ economies is a popular sport, and a lot of people are very invested in the outcomes of those comparisons. For example, I see a lot of people passing around charts like this one, claiming to show that China’s economy has fallen behind the U.S.’ since 2021:

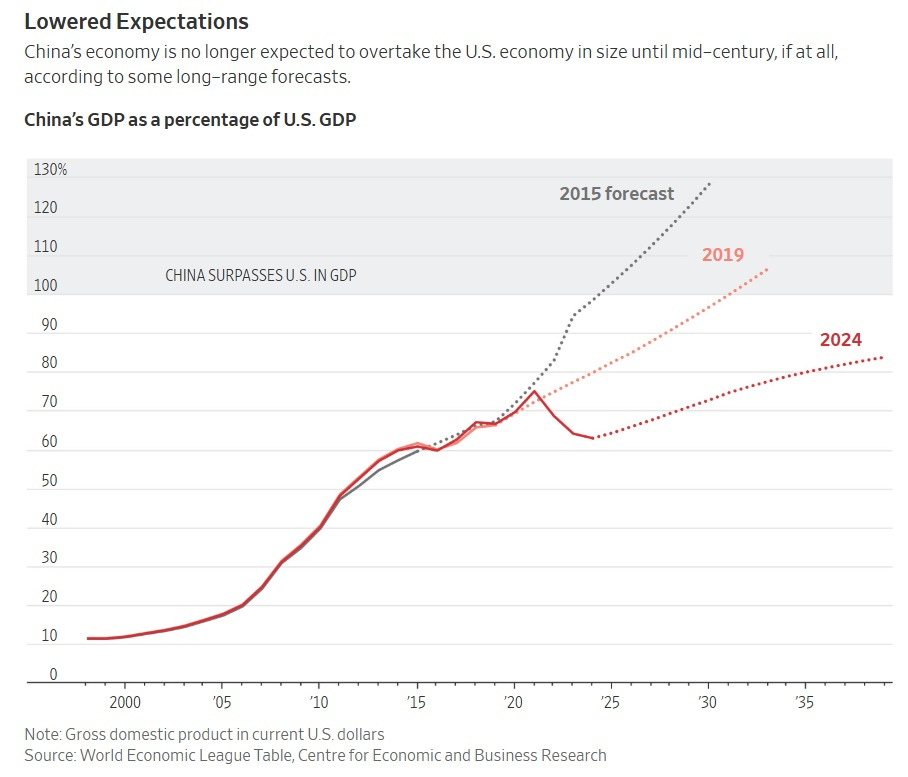

Here’s a more detailed version, from Jason Douglas and Ming Li in the WSJ, showing how forecasts of the sizes of the two economies have changed over time:

In Bloomberg, Hal Brands cites this data to support his argument that the U.S. is still ahead of China in terms of global power:

“[N]early everyone thought China would soon overtake the US as the world’s largest economy. But that crossover point is receding ever further into the future, thanks to robust American growth and deepening Chinese stagnation…Over the past half-decade, the overall gap between the US and Chinese economies — as measured by gross domestic product — has been getting larger.”

So if you just look at this data, you might get the impression that China’s economy is falling behind America’s, and will fail to catch up in the future. But then if you read the news, you hear that China’s GDP is growing at a rate of “around 5%”, while the U.S. grew at only 3.1% in 2024. That’s a strong year for the U.S., but it’s not clear how China’s economy could be falling behind America’s if its growth rate is higher!

The discrepancy here actually has nothing to do with whether or not China’s GDP growth is overstated. Yes, it’s possible that this is the case — for example, Rhodium Group guesstimates that China’s actual growth in 2024 was under 3%. But the charts above actually take the Chinese government’s 5% figure at face value. So why do they show China falling behind America?

The actual reason for the discrepancy is that there are different ways of comparing GDP. The two basic measures are:

- GDP at market exchange rates, also called “nominal”

- GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP), also called “international dollars”, also called “adjusted for differences in the cost of living”

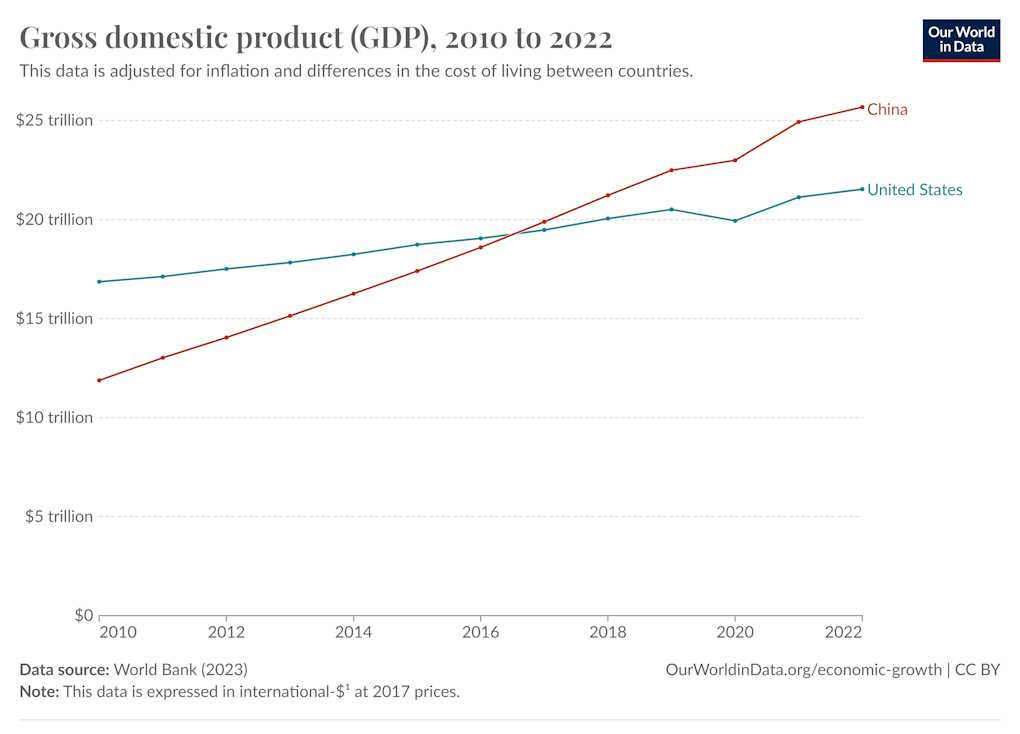

If you use the first of these measures, you see China’s GDP falling behind America’s, as in the two charts above. But if you use the second measure, you see China’s GDP already ahead of America’s, and pulling farther ahead every year (albeit at a slower rate than before 2021):

You’ll notice that this chart says “adjusted for…differences in the cost of living between countries”, and “international $”. That means PPP.

Market exchange rate GDP is measured in U.S. dollars. You just take a country’s GDP numbers (which are measured in its domestic currency), convert that number to dollars using the current exchange rate, and that’s the country’s “nominal” GDP.

That’s pretty easy to calculate and measure. But it means that when exchange rates shift, it makes it look like the relative sizes of different economies also shift, even if they all produce the exact same amount of stuff as before. In this case, it turns out that China’s currency (the yuan or RMB) has been depreciating against the U.S. dollar for years. Here’s a chart of how many dollars one Chinese yuan can buy:

You’ll notice that the yuan was a little bit strong in early 2021, but that in late 2021 its value fell a lot. That’s a big part of the reason that China’s nominal GDP fell relative to America’s over the last three years. The slowdown in China’s official real growth rate was part of the drop, but much of it was just an effect of the cheaper yuan.

In fact, the forecasts that show China failing to catch up to America over the next 15 years are almost certainly assuming that the yuan stays cheap. If the yuan appreciates, China’s nominal GDP will suddenly look like it jumped up. In fact, if China lets the yuan rise a lot, it will look like China’s economy suddenly overtook America’s in size — this is what happened in the late 1980s when Japan allowed its yen to appreciate, and Japan’s nominal GDP suddenly looked like it was almost as big as America’s.

Whether market exchange rates are a good way of comparing countries’ GDP is a subject of debate. On one hand, it’s easy to measure, because exchange rates themselves are clear and unambiguous. And if you care about how many imports two different countries can buy, then market exchange rate GDP is obviously the right comparison. When China’s currency gets weaker, it means China can afford fewer imports.

So if you’re in a third country like South Korea, and you’re asking “Which is a more important market for my goods, China or America?”, the answer has definitely shifted toward “America” over the last three years. And lo and behold, America recently overtook China as South Korea’s largest export market. Market exchange rate GDP might also translate into clout within international economic organizations.

But on the other hand, market exchange rate GDP comparisons have some serious downsides. First of all, exchange rates can be determined by policy instead of by market fundamentals. China used to peg the yuan to the dollar. Now it uses a “managed float”, in which the exchange rate is allowed to fluctuate within a range determined by the Chinese government. In practice, this can look sort of like a peg.

What this means is that if China’s government decided to change the range in which it allows the yuan to trade against the dollar, it might be able to suddenly make China’s economy look bigger than America’s in charts like the ones at the top of this post. And if China decides to make its currency cheaper in order to sell more exports to the world, it can do that too. That will make its economy look smaller in nominal terms, but in fact it will improve China’s export competitiveness, so in some ways it means China’s economy is actually stronger.

More fundamentally, exchange rates don’t affect real living standards. Despite all the headlines about trade deficits and such, most of what Chinese people buy is produced within China, and most of what Americans buy is produced within America. This includes rent, medical care, transportation, and so on. That means that the material living standards of Chinese people and Americans will be determined much more by local prices than by international ones.

PPP is an attempt to adjust for differences in local prices. International organizations like the World Bank send out research teams to various countries to look at local prices of things that aren’t sold on international markets — things like rent and medical care. They then assemble these into a price index. Comparing these price indices across countries gives you a PPP conversion factor that they use to compare economies.

In theory, this gives a better comparison of how much actual stuff different countries produce. But there are many practical problems with this approach.

First of all, the teams that the World Bank and other organizations send out to take stock of local prices won’t necessarily get a great sample of those prices. They might look too much at overpriced cities like Shanghai and not enough at small towns. Or they might look at fancy high-quality apples in a boutique grocery store, not realizing that regular apples cost much less.

On top of that, PPP is often out of date. Prices can change pretty rapidly, while the teams that go out to measure PPP can’t do a thorough survey every year. This can lead to big sudden revisions that change our understanding of the past as well as the present.

As if that weren’t enough, PPP also has a hard time comparing quality between different countries’ goods and services. A haircut in Japan might just be better than a haircut in America, but the people who do surveys for the World Bank may not realize this.1 That quality difference should make Japan’s GDP (PPP) a little higher relative to America’s, but in practice the statistics will often miss it. This is especially important when it comes to the quality of big-ticket items like medical care and the housing stock.

Finally, it’s difficult to compare overall prices between countries because people buy different things in different countries. One country’s people might spend more on health care and less on housing than another country’s. Do they do that because health care is more expensive there, or because they just want more medical care in the first place? It’s hard to say.

All of these measurement issues lead to big discrepancies between countries’ own internal growth numbers and changes in the international PPP comparisons. And they lead to general uncertainty about how much we should trust PPP numbers. When I cite PPP comparisons, someone often pops up in the comment section or the X replies to say “PPP is garbage!”.

That’s wrong — PPP is not garbage, it’s just hard to measure. But when you’re comparing individual living standards — that is, per capita GDP — there’s really just no alternative. How much actual stuff a person in China or America or France can afford depends much more on local prices than on exchange rates, so if you want to know how rich people in these countries really are, you have no choice but to use something like PPP.

When it comes to comparing national power and importance, though, it’s not clear PPP is the right measure either. The cheapness of haircuts isn’t necessarily an important factor in the rise and fall of great powers. But lots of things that are purchased domestically rather than traded on world markets are very important for national power — for example, the salaries of soldiers, locally sourced armaments, local logistics costs, and so on. So if you want to look at military strength, you can’t really use market exchange rates either.

For this reason, some people try to construct a “military PPP” that takes explicitly military expenditures into account. These numbers show, for example, that China’s military spending is much closer to America’s in size than official dollar numbers reflect.

But national power is probably determined by things other than armies alone — for example, lots of civilian consumer manufacturing could be converted to military uses in the event of a major war, as it was in America and many other countries in World War 2. So if you want to know about military capacity, you can’t just look at defense spending — you have to include all the dual-use stuff as well.

Earlier this year, Han Feizi used this sort of comparison to argue that China’s economy is already much bigger than America’s:

“China’s PPP GDP is only 25% larger than that of the US? Come on people… who are we kidding? Last year, China generated twice as much electricity as the US, produced 12.6 times as much steel and 22 times as much cement. China’s shipyards accounted for over 50% of the world’s output while US production was negligible. In 2023, China produced 30.2 million vehicles, almost three times more than the 10.6 million made in the US…On the demand side, 26 million vehicles were sold in China last year, 68% more than the 15.5 million sold in the US. Chinese consumers bought 434 million smartphones, three times the 144 million sold in the US. As a country, China consumes twice as much meat and eight times as much seafood as the US.”

A recent post by the blogger “Austrian China” makes a number of other such comparisons — all of which are in China’s favor.

The argument here — that expensive services don’t represent true economic output, and that comparisons should look mainly at physical goods — is pretty bad when it comes to measuring living standards. Housing, medical care, child care, and other services are incredibly important determinants of how pleasant a life citizens of various countries lead, and to just leave these out of international comparisons and focus only on electricity and cars and ships makes little sense.

But if you’re comparing national power, this sort of argument might make a lot of sense. Nice housing, quality medical care, or high-quality insurance services won’t help you much when a foreign empire’s bombs are raining down on your cities and foreign missiles are sending your country’s fleet to the bottom of the sea.

Fundamentally, this is why I think Americans should take little comfort in the fact that their total GDP at market exchange rates is outpacing China’s. With the world looking more dangerous and warlike by the day, manufacturing is a competition that the U.S. and its allies can ill afford to lose.

Yes, China boosters like Han Feizi and “Austrians” who care only about physical goods are overconfident about the supremacy of the world’s sole manufacturing superpower. But in my judgement, taking comfort in America’s higher nominal GDP numbers is even more dangerously complacent.

This article was originally published in Noahpinion and is republished here with permission.