(and what can you do about it).

Inflation is expected to exceed 10% later this year and could stay above 5% through 2023, 2024 and perhaps even longer.

And that may be optimistic, seeing as the UK’s energy price cap is expected to be 119% higher (£2800 vs £1277) this winter compared to winter last year.

From an investment point of view, the problem is that most investors haven’t experienced that level of inflation during their investing lifetime. In fact, if you’re under 40, you weren’t even born the last time the UK had 10% inflation.

With that lack of experience in mind, I thought it would be a good idea to spend some time thinking about how inflation might impact a portfolio of dividend-paying companies.

To be honest, inflation and macroeconomics is a bit of a rabbit hole, so in this post I’ll just cover what I think are the most important effects.

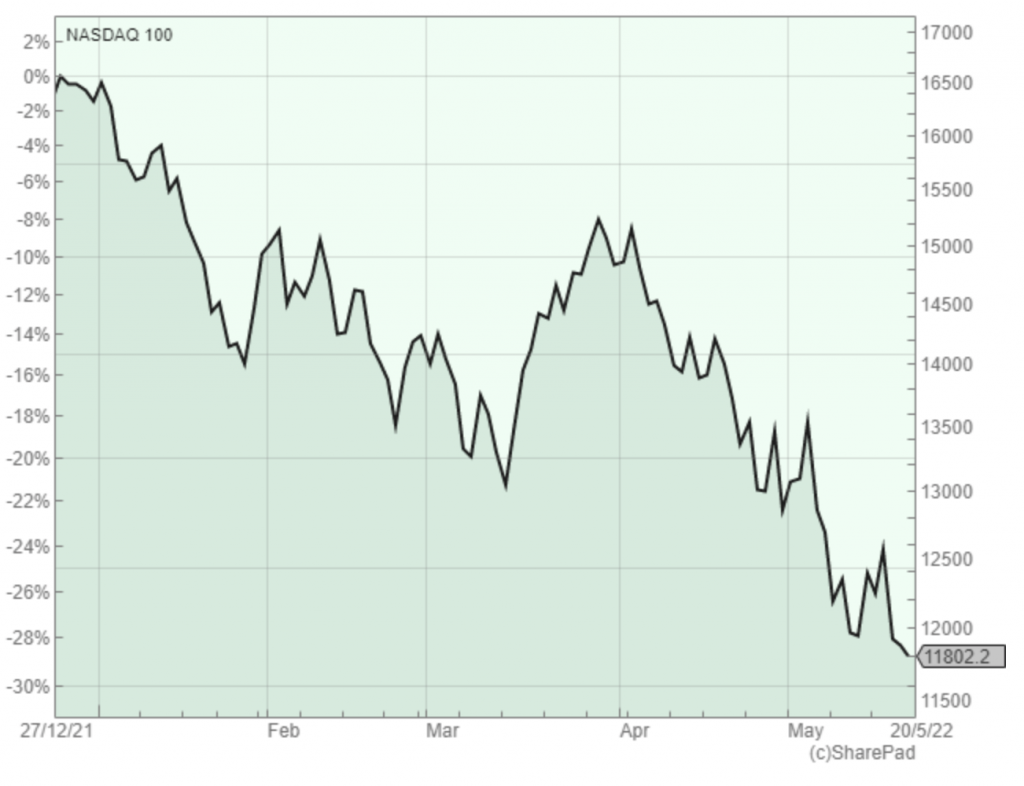

Inflation makes share prices go down

Inflation’s first effect shows up almost before inflation has begun to rise.

The effect is that share prices, especially those of highly-rated growth stocks, begin to go down as soon as investors start to expect higher inflation.

It’s important to be aware of this so that you’re not surprised by it.

Share prices go down partly because investors expect high inflation to eventually cause a recession, or something close to it, but mostly they go down because investors expect interest rates to go up.

And when interest rates go up, the yield on “risk free” bonds (typically government bonds) also goes up, and that has a direct impact on the price investors are willing to pay for shares.

Shares are riskier than bonds, so investors need a risk premium (a higher return) to compensate them for taking more risk. If bond yields go up and if the risk premium stays the same, the yield on stocks will also go up.

And how does the yield on a share go up?

Simple: Its price goes down.

So share prices decline because they’re hit by a double whammy from (a) lower expected earnings thanks to an expected downturn and (b) higher desired yields thanks to increasing bond yields.

Is there a way to avoid this?

Possibly.

You could jump into commodity stocks. They generally do well when inflation is rising, but if you were going to jump into Shell then you probably should have done it last summer as its share price has already gone up 80% since then.

And that’s the problem with tweaking your portfolio to take account of inflation and other macroeconomic factors: You need to (a) be right and (b) act very quickly, otherwise like-minded but fleeter-foot investors will push up the price of inflation-winners and reap the capital gains before you can say “market timing is really hard”.

But don’t be disheartened.

Even billionaire value investor Warren Buffett freely admits that adjusting a portfolio to take account of the changing inflationary and macroeconomic environment is near impossible for mere mortals:

“We will continue to ignore political and economic forecasts which are an expensive distraction for many investors and businessmen.” – Warren Buffett

Rather than tweaking his portfolio to suit the environment, Buffett’s approach is to always be invested in a portfolio of companies that are very likely to survive and thrive over the long-term, regardless of what inflation and the economy throw at them.

However, even the highest quality companies can see dramatic share price declines when inflation rises, so Buffett’s second line of defence is to own quality companies when their price is already materially below fair value.

Owning stocks where the share price is below fair value can help reduce downside risk because:

- The price is already low and there are limits to how far below fair value a stock’s price will go

- The lower price should produce a higher dividend yield and that higher income could partially offset any price decline

- If the price falls further below fair value, then the lower price might be an excellent opportunity to buy more shares

The last point is perhaps the most important. If you own quality companies at attractive valuations and you’re investing for the long-term, then falling share prices should, in most cases, be more of an opportunity than a risk:

“Every decade or so, dark clouds will fill the economic skies, and they will briefly rain gold. When downpours of that sort occur, it’s imperative that we rush outdoors carrying washtubs, not teaspoons.”– Warren Buffett

Inflation squeezes profit margins

Inflation’s second major effect is that companies begin to see their costs rising faster. The price of energy goes up, the price of raw materials, components and goods goes up, and eventually the cost of labour goes up.

If a company’s expenses are going up because of inflation then its profit margins and profits are going to get squeezed. If costs go up fast enough, profits can even be squeezed out of existence.

To avoid that unhappy scenario, companies have two main options:

- Cut costs, or

- Pass inflation onto customers by raising prices

Cutting costs is a good place to start because good companies are always looking to cut costs. They could substitute expensive raw materials for cheaper substitutes, use less raw materials (as companies like Unilever and AG Barr have done by making bottles and cans thinner) or you can replace humans with machines.

This takes time and it will only get you so far. The only sustainable way to deal with inflation is to pass it onto the customer, by raising the price of goods and services.

But raising prices is easier said than done. Customers are probably already being squeezed by rising inflation, so the last thing they’ll want to see is yet more price rises.

To have any chance of passing inflation onto customers, a company needs to have at least some degree of pricing power.

Pricing power means a company can consistently increase prices without alienating or losing too many customers.

So how do we find companies with pricing power?

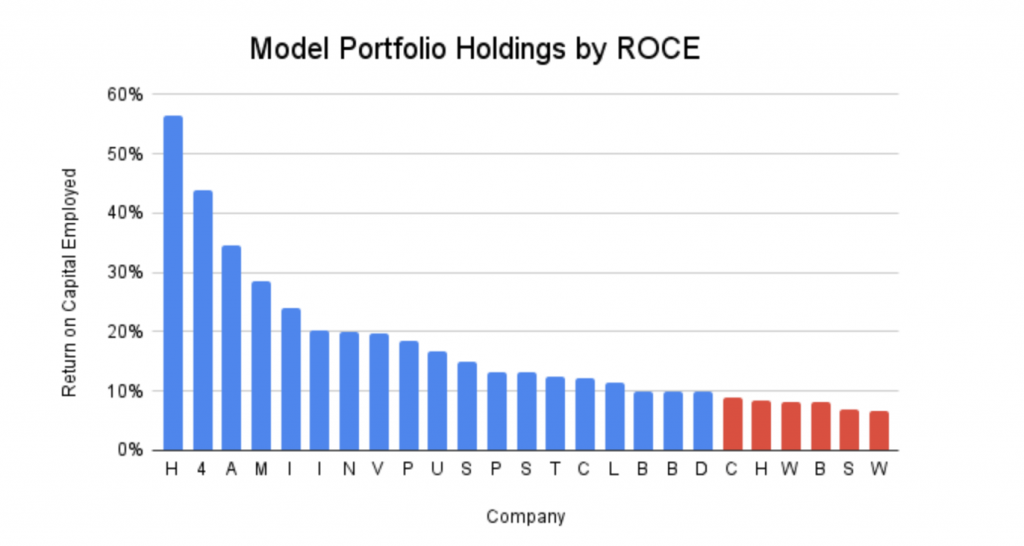

My suggestion would be to look at a company’s return on capital employed, which is the amount of profit a company generates from its fixed capital and working capital.

In the UK, the average post-tax return on capital is around 10%. If a company can consistently produce returns on capital that are above 10% then it almost certainly has pricing power.

If it didn’t, competitors who were willing to earn slightly lower returns (but still above average) would undercut the company on price and steal its profits. The fact that a company has consistently earned above average returns on capital over many years is a good sign that either (a) it can charge higher prices without losing customers, (b) it has lower cost operations or (c) both.

Because a consistently high return on capital is good evidence of pricing power, I have a related rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in companies where return on capital is consistently above 10%

And according to Warren Buffet, it’s a good idea to own these companies at all times and not just when we’re seeing high inflation.

For example, my UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio currently holds 25 companies, shown below in order of their ten-year average net return on capital employed (ROCE):

Only six out of 25 holdings (highlighted in red) have average returns on capital below 10%, while a handful have generated returns on capital well above 20%. And of those six, most would have average returns on capital of more than 10% if it wasn’t for seriously depressed earnings caused by the pandemic.

So, companies with pricing power have a better chance of passing inflation onto customers and, in an ideal world, they’d be able to pass all inflation onto customers almost immediately. But in the real world that isn’t usually possible.

In most cases, inflation gets passed on over a period of time because (shockingly) customers are usually reluctant to pay higher prices.

Unilever (which I currently hold), is a good example of this. The company buys all manner of commodities to make ice cream, deodorant, soap and hundreds of other products and, over the last year or so, Unilever has seen extreme levels of inflation across many commodities from wheat to soybean oil to natural gas.

Unilever does have pricing power, which shows up as a 17% average net return on capital. But even with that much pricing power, it cannot immediately raise prices by the 10%+ required to offset inflation. If it did, customers would switch to products from competitors who were willing to take some short-term pain by raising prices slowly.

As things stand today, Unilever expects this year’s inflation to be fully passed onto customers over the next couple of years. And until that inflation is fully passed on, its expenses will be rising faster than its revenues and that means its profit margins are going to get squeezed.

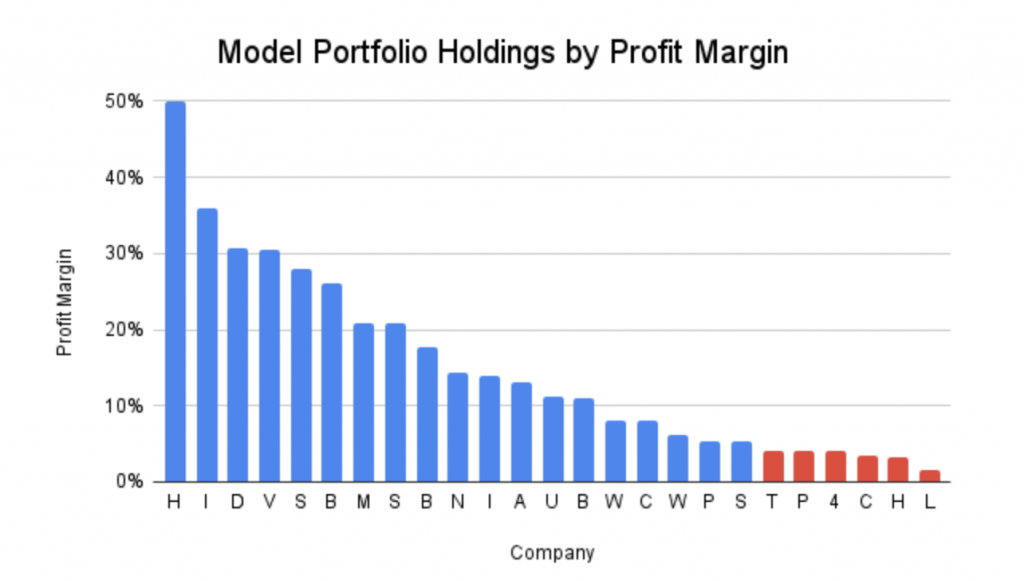

More generally, the longer it takes to pass on inflation, the more profit margins are going to get squeezed, so you can think of profit margins as a buffer that protects a company from inflation. At least for a while.

This puts fat margin companies in a good place as they can raise prices slowly, helping them to retain more customers. On the other hand, companies with thin profit margins must pass inflation onto customers quickly, otherwise their profits will evaporate.

In some thin-margin industries this isn’t necessarily a problem because revenues are charged as a fixed percentage of the cost of goods sold. For example, many distributors have profit margins of less than 5%, but their revenues are charged as a fixed percentage of the items being distributed, so when the price of the item being distributed goes up, the distributor’s fee immediately goes up as well.

But that isn’t usually the case and thin margins can be a serious problem when inflation is high.

To avoid these problems the obvious thing to do is avoid low margin businesses, so here’s my rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in companies where profit margins are consistently above 5%

5% is a fairly low hurdle for many companies, but it’s enough to filter out companies with little to buffer them from rising inflation.

Here’s another snapshot of my portfolio’s holdings, sorted by profit margin.

As with return on capital, six holdings (not the same six that had weak returns on capital) have profit margins below my 5% threshold. Three of those are life insurers and the low profit margin doesn’t accurately reflect the strength of these businesses. Here’s why (skip this bit if you’re not interested in life insurers):

Life insurers don’t have profit margins in the normal sense don’t because they don’t have revenues. You could use premiums earned during a year as a proxy for revenue, but some life insurers buy “closed books” of life and pension policies where new policies aren’t being written. Profits are made as the books “run off” (when policyholders die), but no new policies are written so no premiums are earned leaving no good proxy for revenue.

To get around this, I calculated life insurer profit margin as the margin between claim reserves (premiums held within the company to cover future claims) and claim liabilities (expected future claims). There is typically a low-single-digit percentage gap between these two figures, hence their low “profit margin”.

Why is a thin margin between claim reserves and claim liabilities probably okay? The answer is that our lifespans are very predictable when averaged across thousands or even millions of people. This predictability means that life insurers can operate safely with very thin margins between money reserved to pay future claims and the expected cost of those claims.

In other words, the apparently low “profit margin” of life insurers is not a sign of weakness; it’s a sign that mortality is very predictable.

If I ignore the thin margins of life insurers then the portfolio has three companies with margins consistently below 5%. In each case, I think there are legitimate reasons why their margins are so low.

Two of these low margin businesses are distributors and as I’ve already mentioned, distribution is an inherently low margin activity. In both cases, their revenues are mostly generated as a fixed percentage of the items being distributed, which makes it a lot easier to pass inflation on to customers.

The third low margin holding is a supplier of utility services such as electricity and gas. This is really another form of distribution, with the company distributing electricity and gas rather than carpets or cups. And as with other distributors, its revenues are, to a large extent, charged as a fixed percentage of the cost of thing being distributed (electricity and gas), so once again input cost inflation should be relatively easy to pass on to customers.

The point is that low profit margins are generally something to avoid, but not always, and it depends on the specific attributes of the business.

Inflation reduces demand

When general inflation is high, demand for most goods and services usually falls. That’s because prices for non-discretionary costs like energy and property go up while income growth tends to lag behind, so customers have less disposable income to spend on everything else.

To help them cope with this squeeze, people and companies will cut back on expenses that are easiest to cut back on, which means those that are easily avoidable or deferrable.

Consumers might delay refurbishing their home, taking an overseas holiday or going to a fancy restaurant, and companies might cut back on advertising or defer the construction of a new factory.

On the other hand, people are still going to buy things like electricity, food, nappies and car insurance, and they’re still going to have medical procedures, even if inflation is running at 50%. They might downgrade to a cheaper brand or reduce their consumption a little, but they’re still going to need these things come rain or shine.

So when inflation is high and rising, companies that are part of the supply chain for big ticket deferrable goods or services could be hit harder, while companies that sell small-ticket, repeat-purchase necessities are likely to fair better.

Unilever is, once again, a good example of this phenomenon. It sells products like deodorant, detergent, soup and sausages. These products don’t cost a huge amount and they don’t last very long, and seeing as most people aren’t going to give up deodorant anytime soon, demand for these products will remain robust no matter how bad inflation or the economy gets.

The obvious thing to do then, if you’re interested in avoiding the worst downsides of high inflation, is to invest in defensive businesses.

In my case, while I do have a preference for defensive companies, I don’t completely exclude cyclical stocks. That’s because high quality cyclical businesses can actually benefit from market disruptions like high inflation and deep recessions. It works like this:

When high inflation causes a recession, most companies in most cyclical industries will see their revenues and profits decline. Weaker competitors will suffer the most and many of the weakest will go bust. Meanwhile, high quality market leaders will see smaller revenue and profit declines and, thanks to their stronger balance sheets, they’ll be able to take market share from their weaker peers by investing more into advertising, or by hoovering up the best people from competitors that have gone out of business.

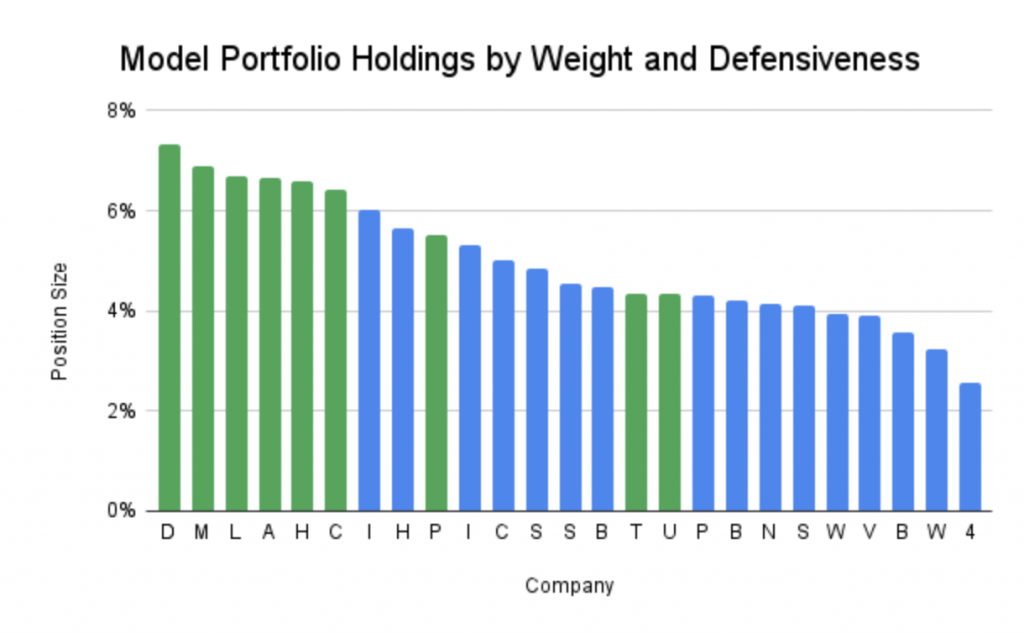

So rather than excluding cyclical businesses, I prefer to gently tilt my portfolio toward defensive holdings by giving them slightly larger position sizes.

For example, I aim to hold 20-25 companies in my UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio, so I use the following rules for default position sizes:

- My default position size for defensive companies is 4%

- My default position size for cyclical companies is 3%

These default sizes are then adjusted up or down depending on valuations, but defensive positions will always be about 1% larger than similarly attractive cyclical positions.

This gently tilts the portfolio towards defensive companies, even if there aren’t that many of them in the portfolio.

The chart above shows all of the portfolio’s holdings in order of position size, with defensive holdings in green and cyclical holdings in blue.

At first glance this doesn’t look like a very defensive portfolio because there are 16 cyclical holdings and only nine defensives. However, because I give the defensive holdings larger positions, they make up 45% of the portfolio by weight, so the portfolio is almost evenly split between cyclicals and defensives.

To be honest, I’d be happier if the portfolio was more weighted towards defensives, but in reality, there are only so many defensive stocks trading at attractive valuations. What I don’t want to do is fill the portfolio up with defensive holdings where the valuation and the expected returns are no better than average.

So as things stand today, I’m comfortable with a near 50/50 split between defensives and high-quality cyclicals.

Inflation makes capital expenses more expensive

One line of thinking is that it’s best to own asset-rich companies during times of inflation, because the real value and earnings power of these assets is expected to increase in line with inflation.

In some very specific situations that’s largely true.

For example, let’s say you bought the average UK house in 1993 for £50,000 (yes, believe it or not that was the average house price in early 1993). If you rented that house to tenants your rental income would have gone up, ahead of inflation, over the following 30 years. Today, the average rent for a new tenancy is £1,091 per month or £13,092 per year. If that was the rental income on the house you bought in 1993 then your property would have a gross cash income of 26% per year on the purchase price.

And of course, the market value of the house would also have increased to something like £270,000 (according to Nationwide).

Those are very impressive returns, but we’re ignoring operating expenses such as replacing worn out carpets, cookers and door handles. These go up with inflation, so they have the potential to seriously undermine the returns of asset-rich businesses.

Fortunately for you (in this example), the operating expenses for a rental property are usually very low relative to rental income, so most of that growing rental income does end up in your bank account.

Turning the focus back to companies, what we might want to look for is companies where:

- The business depends on expensive capital assets

- Revenues from those assets is expected to go up with inflation

- The assets were purchased years ago

- The assets don’t need to be replaced for many decades

- Operating expenses for those assets are low

Unfortunately, very few companies have these characteristics.

The main problem is that most capital assets need to be upgraded or replaced every few years if the company is to maintain its competitiveness.

Yes, the structure of a warehouse might not change much from one decade to the next, but most warehouses have seen huge amounts of change over the last few decades, with more and more robots and fewer and fewer people. Those robots cost a lot of money, and to make matters worse, the operating cost of a warehouse isn’t exactly negligible.

In most cases then, companies with lots of expensive capital assets have to upgrade and replace those assets on an ongoing basis, and that’s a really bad place to be when inflation is high.

“For years the traditional wisdom – long on tradition, short on wisdom – held that inflation protection was best provided by businesses laden with natural resources, plants and machinery, or other tangible assets (‘In Goods We Trust’). It doesn’t work that way. Asset-heavy businesses generally earn low rates of return – rates that often barely provide enough capital to fund the inflationary needs of the existing business, with nothing left over for real growth, for distribution to owners, or for acquisition of new businesses.” – Warren Buffett

For example, imagine a company with a significant amount of tangible assets, such as factories and heavy machinery, and they need to be upgraded or replaced every few years if the company is to stay competitive.

If inflation is running at 10%, the company will need to increase the value of its assets by 10% each year if it is to retain its earnings power in inflation-adjusted terms (a £100,000 truck purchased last year might need to be replaced with an identical truck this year, which thanks to inflation will now cost £110,000).

However, if this company has a return on capital of 5% then it literally cannot afford that level of investment, even if it paid no dividend and reinvested every penny of profit into upgrading and replacing its assets.

The only way to fund that level of expansion would be to (a) raise fresh capital from shareholders via a rights issue or (b) fund the investment with debt, neither of which is a particularly attractive option.

So how can we avoid these companies?

First of all, we can look at our old friend, net return on capital employed. If net return on capital employed is consistently close to or below the level of inflation you might reasonably expect to see at some point in the business cycle, then this might be a company to avoid. Here’s my rule of thumb again:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in companies where net return on capital is consistently above 10%

10% is low enough so that it isn’t overly restrictive, but it’s high enough so that companies passing this rule should be able to self-fund inflation-beating growth under most circumstances. And they should generate enough spare cash to also fund a sustainable dividend.

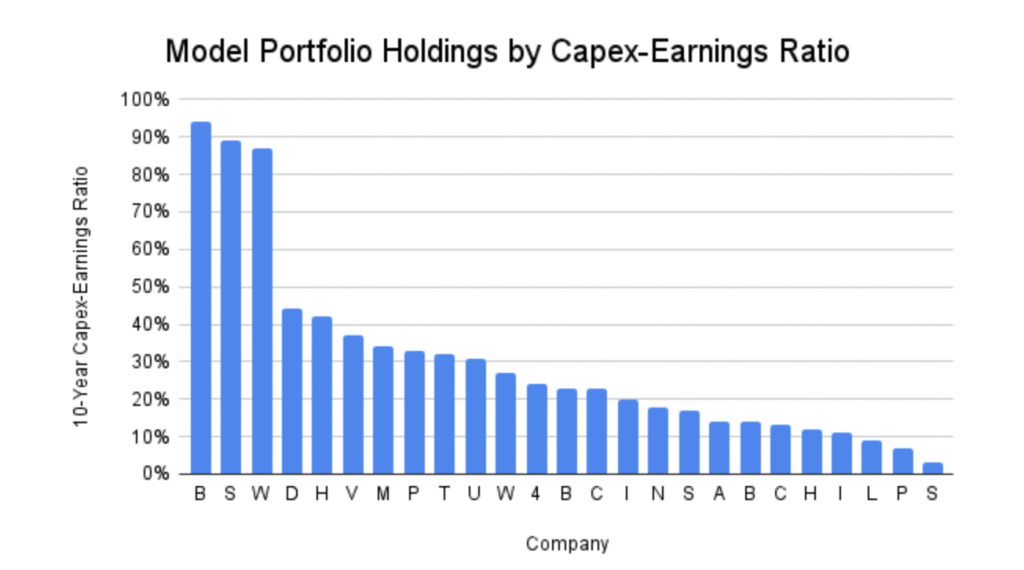

I also like to look at the ratio of capital expenses (capex) to earnings, because high inflation can seriously impact companies that consistently spend a lot on capex.

If you’re not familiar with capital expenses, you can think of them as money spent on assets that will last more than one year.

For example, if a company buys a truck that is expected to last ten years, that’s a capital expense. The interesting thing about capital expenses is that although they reduce cash flows, they don’t reduce earnings.

Why doesn’t capex reduce earnings?

Well, you can think of the income statement (where revenues, expenses and profits are summarised) as a link between two balance sheets (recording assets, liabilities and net asset value) on separate dates. Very simply, income increases net assets on the balance sheet while expenses reduce net assets.

So, if a company buys a truck for £100,000, its cash on the balance sheet will go down by that amount but it will also gain a capital asset (the truck) of the same value. One offsets the other and the company’s net asset value doesn’t change. And if the net asset value didn’t change because of that transaction then no expense is recorded on the income statement.

But that isn’t the end of the story.

If the truck is expected to last ten years before being scrapped, it will depreciate in value each year. As the truck depreciates, it loses value even though the company hasn’t paid out any cash. As the truck loses value, the company’s net asset value goes down. And if the net asset value went down because of depreciation then depreciation must be recorded as an expense on the income statement.

To put it more simply: capex reduces cash flows and depreciation reduces earnings.

Why is this a problem for high capex companies in times of high inflation?

The answer is that depreciation relates to capital assets purchased in the past when prices were much lower, while capex relates to the purchase of new capital assets at today’s inflated prices. Because of that, when inflation is high, capex can be significantly higher than depreciation, even if the company isn’t growing.

Here’s an extreme example:

Imagine a company earning £100 million per year and paying a dividend of £50 million. The dividend is covered twice over so investors are relaxed. Because inflation is high, the company is spending £200 million on capex each year whereas depreciation is £100 million per year. This isn’t growth capex; this capex is required just to stand still.

We can reflect the negative impact capex has on cash flows by adjusting the company’s earnings.

All we need to do is remove the depreciation expense (because it’s a non-cash expense) and replace it with capital expenses (because capex is a cash expense). This is a simplified version of free cash flow, which is a useful measure for seeing how much spare cash a company is generating (spare cash which could be used to fund dividends or buybacks).

In the above example, adding £100 million of deprecation onto £100 million of earnings gives the company an earnings before depreciation figure of £200 million. If we then subtract the £200 million of capex that gives the company a simplified free cash flow figure of precisely zero.

This leaves the apparently safe “twice covered” dividend completely uncovered in terms of cash generated by the business, which isn’t great.

As I said, that’s a fairly extreme example, but the general point stands: Capital intensive businesses are usually not a great place to be when inflation is high.

To avoid companies where high levels of capex could prove problematic, I use the following rule:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in companies where the ten-year capex-earnings ratio is below 100%

In my experience, companies with capex consistently below this level rarely have cash flow problems caused by their capital investments. Here’s a quick look at how my UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio stands today in terms of capital intensity:

There are three holdings close to the 100% limit. Two have engineering plants full of very expensive equipment, so a reasonably high capex-earnings ratio is an inevitable part of their business model. The third is actually a relatively capital-light business where the capex-earnings ratio has been skewed upwards by very large losses (negative earnings) during the pandemic.

So in practical terms, there are two holdings out of 25 that are somewhat capital intensive and I’m comfortable with that.

Inflation makes debt cheaper and more expensive

Let’s return to the earlier example of a buy-to-let property purchased in 1993 for £50,000. Let’s say the property was purchased with a 30-year interest-only mortgage with a 10% interest rate (because 10% really was the average mortgage interest rate back then).

The important point is that both the amount borrowed and the interest payments are fixed in nominal terms, so they never go up.

However, thanks to the joys of inflation, the annual rental income has increased fairly steadily to a whopping £13,092, so the property now generates a cash income (ignoring running costs) of £8,092 (rental income minus £5,000 of mortgage interest).

Also, if you sold that very average property today you might get £270,000, leaving you with a capital gain of £220,000 after paying the original £50,000 loan back to the bank.

What this means is that, all else equal, inflation can be good for companies that have lots of debt, as long as:

- The interest rate is fixed for the full term of the loan

- The loan doesn’t have to be paid back for many years

- The debt was used to buy productive assets with earnings power that is expected to grow at least in line with inflation

- The assets’ operating costs (which do go up with inflation) are relatively small

That list is a reasonable description of many utility companies, where long-dated debt is used to fund investments in power plants or wind or solar farms and where the related income is expected to go up with inflation for many decades.

However, the downside is that the world is an uncertain place and very few companies can carry enough debt safely to make this line of thinking relevant.

In my experience, investing in companies with high levels of debt is almost always a bad idea, and adding in the stresses of high inflation isn’t going to change my opinion.

My preference is to focus on companies that have a zero debt or low debt policy, because they know the future is uncertain and a strong balance sheet is one of the best defences against that uncertainty.

If that uncertainty shows up as unexpectedly high inflation, they know that debt raised today which is barely affordable with a 5% interest rate would become wholly unaffordable if it had to be replaced with new debt with a 15% interest rate five years later.

For companies looking to produce sustainable growth over many decades, the risk/reward trade-off from carrying lots of debt is almost never worth it.

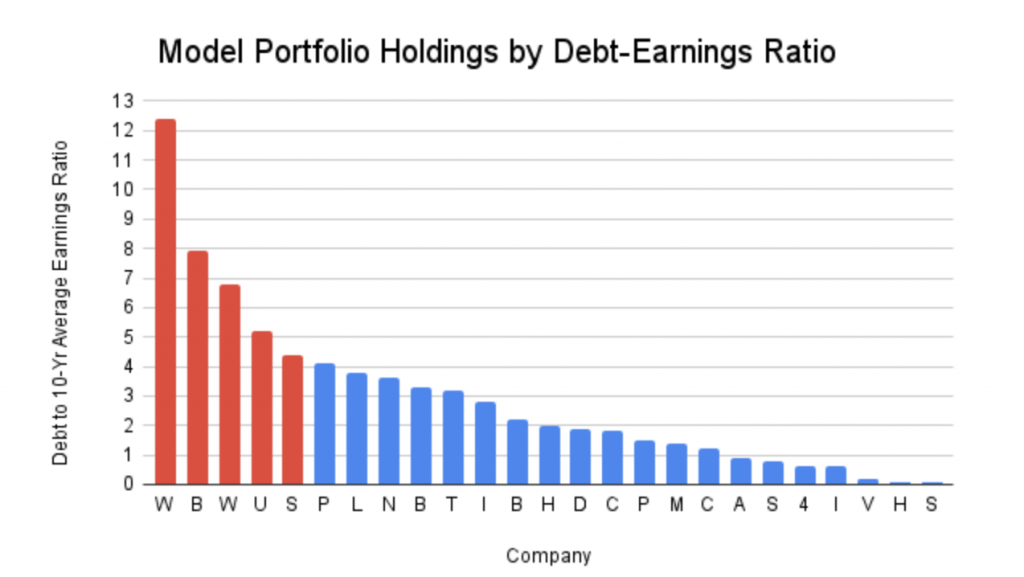

Fortunately, it’s easy to avoid the risk of high debt interest rates by excluding companies that carry a lot of debt. As you might expect, I have rules for this:

- Rule of thumb: Avoid cyclical companies where the debt to average earnings ratio is above four

- Rule of thumb: Avoid defensive companies where the debt to average earnings ratio is above five

I compare debts (borrowings and leases) to earnings average over ten years, because earnings in a single year can be misleading. Here’s that ratio for all of my current holdings:

As you can see, there are five holdings with more debt than I’d like. Two of those high debt-earnings ratios are partly due to negative earnings through the pandemic (notably the one with a debt-earnings ratio of 12). The others just have more debt than I’d like.

Ideally there wouldn’t be any over-indebted companies in the portfolio, but this is the real world and sometimes managers do things you’d rather they didn’t. Fortunately, most of these companies are reducing their debts, but if any of them continue to pile on debt to ridiculous levels then yes, I would remove them from the portfolio.

Inflation protection that is always switched on

This has been quite a long post, so I’ll summarise the main points before signing off.

First of all, inflation and its effects are incredibly hard to predict, so adjusting a portfolio in real-time to cope with changing inflation expectations is almost always a bad idea. Instead, having inflation protection switched on at all times might be a better idea.

That means always being invested in a diverse basket of companies that have:

- Protection from falling share prices because their share prices are already below fair value

- Protection from rising input costs because pricing power and wide margins enable them to safely pass inflation onto customers

- Protection from falling demand because they sell products and services that are low-cost, non-durable necessities

- Protection from rising capital expenses because they’re relatively capital-light

- Protection from rising debt interest rates because they have little or no debt

I’ll end by repeating the wise words of Warren Buffett:

“We will continue to ignore political and economic forecasts which are an expensive distraction for many investors and businessmen.” – Warren Buffett

Originally published by UKDividendStocks.com and reprinted here with permission.