Another instalment in a series of articles detailing how to design a secure, income-producing portfolio.

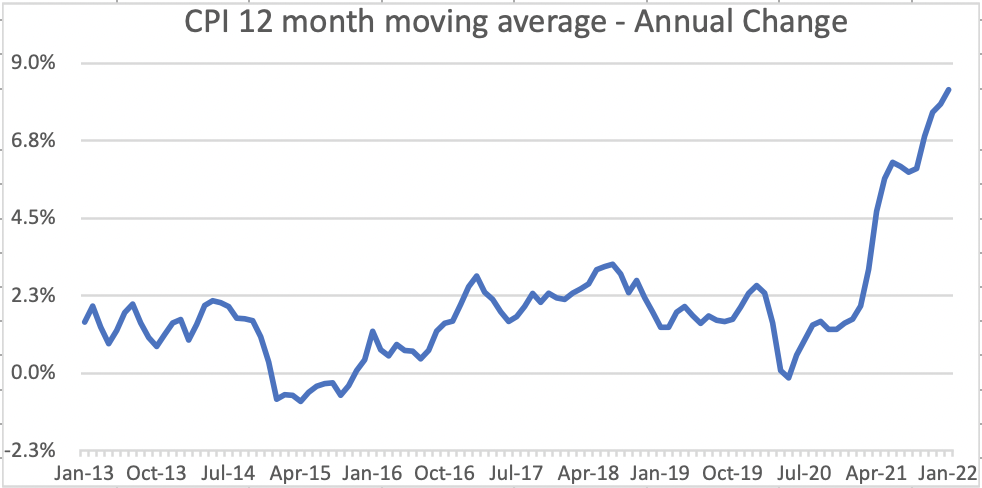

According to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), for the 12 months ended January 2022, inflation soared to 7.5%, the highest annualised chance since 1982. During that same 12 month period, the S&P 500 rose 20%. Inflation decreases buying power and therefore must be subtracted from investment returns, otherwise you might think you are growing richer while you are, in fact, growing poorer. While inflation turned higher last year, stocks did as well. This means, that the stock market went up 20% in a year, while buying power decreased 7.5%, so we’re essentially enjoying inflation-adjusted return of 12.5%, right?

Well, no. That would be correct if the CPI were a good measure of the inflation that we experience in our daily lives. But it isn’t. The CPI methodology treats different categories of consumer goods separately. For eample, we see that the things we NEED – such as medical care, housing and food – are growing more expensive at a rate far greater than the average. Meanwhile the things we WANT, such as televisions, computers, cars and virtually all electronics, show very little inflation because CPI adjusts these categories for ‘improvements’. So if the average new car or iPhone costs 3% more than last year, but includes more technology, the CPI for that category will be much lower or even negative. For most of us, this does not average out to an overall inflation rate on par with the official number put out by the CPI. To put it bluntly: no one experiences CPI-level inflation. Depending on which alternative measure you use, experienced household inflation is approximately 2-4x the long-term average CPI rate.

The upshot of this is that most investors have sold inflation short. Their portfolios are constructed in a manner to benefit when inflation falls or remains low. If you hold your wealth in liquid securities then you’re essentially making a bet that inflation will remain low, because inflation reduces the return on those assets. The CPI encourages us to make that bet by telling us that inflation is reliably low. If we confronted the fact that the inflation rate, we actually experience is several points higher, we might not be as bullish on stocks and bonds, which offer no built-in mechanism to protect us from inflation.

Illiquid assets, meanwhile, do offer such protection. How? They’re supply-constrained, which means they cost money to reproduce. Their replacement cost, in construction materials and labour, is rising at a rate that is two or even three times faster than the CPI. In other words, if you buy an illiquid asset today, and the cost to produce a competitive asset is rising at two or three times CPI, that’s the definition of making money. You’ve won.

Yet liquidity bias has most people sticking with stocks

and bonds.

Liquidity isn’t bad – it’s overconsumed

Maybe all this sounds alarmist. After all, at its core staying liquid means you have access to cash. Isn’t access to cash a good thing? More to the point, isn’t it absolutely essential?

Yes, you need access to cash. But most people don’t need access to 100% of their portfolio in two business days. Or 90%. Or 80%. The truth is that investors’ expectation that they should be able to get their money out in a matter of hours is misplaced, at least for some significant share of their portfolio. If you’re in it for the long haul, in fact, this expectation is counterproductive—because it’s expensive.

Meanwhile, the glut of demand for liquidity bids up prices. Like all products, liquid assets are priced to meet demand, and because most people want most or all of their portfolio in liquid securities, those securities have gotten very expensive. How do we know that liquidity is so expensive? From the volatility.

How volatility makes liquidity expensive

Events that make people nervous lead them to sell, and big events sometimes send the whole market to a precipitous V-bottom sell-off, as I’ve described. This phenomenon is so well-known that the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and a few other markets are subject to what’s known as circuit breakers. After the crash of 1987, President Reagan convened a task force that ultimately recommended placing limits on dramatic price swings. Today, the NYSE is governed by three different circuit-breaker levels, in which a dramatic price decline leads either to a 15-minute pause in trading or, in the case of a level three, in which the market hits a precipitous 20% decline in a single trading day, trading is halted for the remainder of that day. The point of these circuit breakers isn’t simply to curb the damages that result from volatility, it’s to give market participants a chance to access better information and make reasoned decisions.

The volatility that circuit breakers are intended to limit is the direct result of market participants having easy access to a sell button. If the prevailing rule weren’t T+2, but rather T+30 or T+365, the temptation to sell could be very different. Events in the news cycle wouldn’t cause the same disruption. But the rule is T+2 and events in the news cycle do cause panic in the markets. Volatility is the result of liquidity.

You can easily see how liquidity begets volatility by looking at price data for a class of assets known as real estate investment trusts, or REITs. These trusts contain income-producing real estate and many of them are traded on the NYSE. From their peak in 2008 to a trough in 2009, REITs fell almost 80%. But how much did the value of the underlying assets – the real estate itself – drop over the same period? Depending on which index you looked at, the decline in the actual real estate was more like 20 to 30% (a drop that was itself attributable to appraisers, as I described above). Shares of REITs and the real estate contained in those REITs are supposed to be the same asset. They are supposed to be the very same investment. Yet the one with the accessible sell button evidences two to four times the volatility of the other.

Liquidity produces volatility. And volatility, in turn, destroys wealth as investors typically behave as a herd and sell at panic lows. Though it’s the opposite of what they intend, market participants end up selling securities when the market is down and buying them back later, when the market is on its way up. In other words, a lot of people lose a lot of money. (Of course, there’s someone on the other side of every one of those trades who profits off the other person’s loss. There will always be large banks and the largest trading houses who have nearly infinite access to capital, thanks to leverage, who are typically the winners at market lows.) This wealth destruction is often temporary, but it’s always painful. Recovery can take months, years or decades. For most market participants, volatility is the steep cost of staying liquid.