This article was originally published in October 2020.

With this novel, Raymond Chandler transformed the genre from the simple whodunnit to the philosophical musings of a troubled, flawed protagonist.

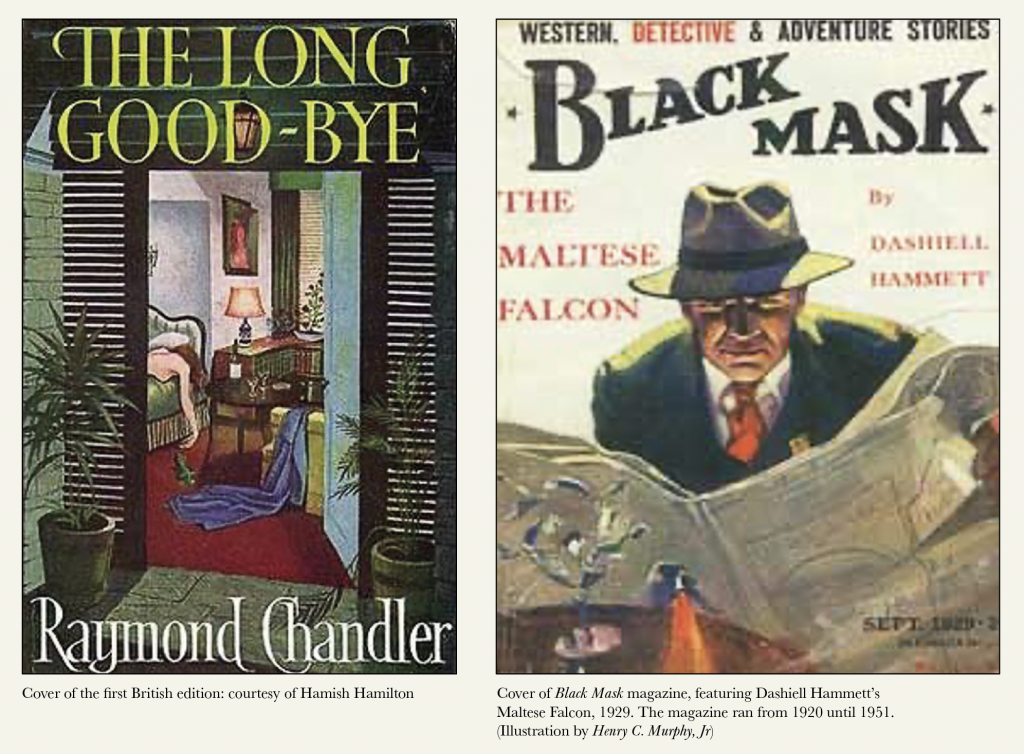

Raymond Chandler’s novel The Long Goodbye, published in 1953, was a turning point in the evolution of the crime thriller and its familiar main protagonist, the detective. After this it became permissible, a requirement even, for the heroes of such stories to express human frailty, to have emotional baggage, rather than being either genius toff or hardboiled crime-fighter mumbling a few words about ‘doing the right thing’ whilst battling through to a final showdown with the bad guys.

In Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), we see the archetypal brilliant sleuth introduced for the first time. From then until the 1920s, through the books of Wilkie Collins, Conan Doyle, Dorothy Sayers, and the early works of Agatha Christie, the investigator at the centre of most crime thrillers would remain a highly educated, analytical amateur. The job of a professional policeman would have been regarded as too grubby, too much like a trade, for a dashing gentleman inquisitor. Their natural habitat and that of their friends and clients was, after all, the drawing room and the country estate.

But from the end of the First World War onwards, starting in the US, the tone, style and intended audience of the crime thriller began to change. The stories of Dashiell Hammett, which appeared throughout the 1920s in mystery and detective ‘pulp magazines’ such as Black Mask, are mostly tales of the mean streets of the city. The main characters are tough rather than privileged, the settings are often seedy and – unlike the exotic locations of many Edwardian thrillers – would have been familiar to their readership. Also, crucially, these entertainments were cheap and easy to source from the local newsstand.

It’s a more complex and cynical world perhaps

but also one where the characters are more open

and prepared to admit to the pain of loss

There’s plenty of fighting, drinking, gambling and sex woven into Hammett’s narratives, and they have an authenticity that was derived from his own experience as a detective at the Pinkerton agency. His heroes, such as Sam Spade, are strong and resourceful – men of integrity and determined pursuers of the truth – but they don’t give too much away about themselves. Indeed, in The Maltese Falcon (published in book form in 1931), none of the characters describe their thoughts and feelings at all – Hammett tells us only what they say and do and how they look. Even by 1952, when writers Mickey Spillane and Jim Thompson had just published two big-selling American noir thrillers about gangsters and tough guys, Kiss Me Deadly and The Killer Inside Me, the emphasis is still on the action rather than on developing the well-rounded characters found in most other forms of fiction.

The earlier work of Raymond Chandler also presents his hero, Philip Marlowe, as taciturn and tight-lipped. In stories like Farewell, My Lovely (1940) and The Little Sister (1949), Marlowe is smart, honourable and fast-thinking. We know he lives alone and may have a difficult relationship with alcohol but although we get glimpses of his sometimes morose view of the world, we are told little else about him. In 1953, with The Long Goodbye, all this changes. The Philip Marlowe of this story, Chandler’s last major work, is the model for the flawed, damaged modern detective character which has endured to this day.

The Long Goodbye is set in familiar Chandler territory. It’s southern California and Marlowe is, as always, a latter-day knight-errant caught up in dangerous, hard-to-fathom events not of his making. As in his previous quests, he’s trying to earn a few dollars by unravelling a mystery but is also helping others because it’s the right thing to do. When happenstance and his own incorrigible Good Samaritan instincts intersect, Marlowe befriends and saves the louche, often drunk but always charming Terry Lennox from a difficult situation. Lennox is an emotionally and physically scarred war hero who has married money and trouble in equal measure; late one night he turns up on Marlowe’s doorstep on the run from the cops, who think he’s murdered his wife. Marlowe shows loyalty if not wisdom in delivering his friend to a safe haven over the border in Mexico because he believes Lennox is innocent. Not for the first time in his career, Marlowe is the only one who can see the truth.

There are differences here, though, from previous Marlowe stories. The backdrop is now post-war 1950s America and both Marlowe and his creator are 14 years older than they were when Chandler’s breakthrough novel, The Big Sleep, was published in 1939. It’s a more complex and cynical world perhaps but also one where the characters are more open and prepared to admit to the pain of loss and the regret of mistakes made. Society is changing, and Chandler and the art of detective story writing are trying to keep up to date by adopting a broader view. The Long Goodbye represents a milestone in the journey of the crime thriller into something more mature than the two-dimensional whodunnit.

In a letter to the editor of The Long Goodbye, Chandler’s thoughts on the modern detective story show that while at the age of 65 he is weary, he has also acquired wisdom: “one grows up… becomes complicated and unsure; interested in moral dilemmas rather than who cracked who on the head. And at that point one should retire and leave the field to younger and more simple men.”

Chandler used the book as a vehicle for his own musings on such topics as what makes a person drink, the saving graces of the big, ugly city, the nature of friendship and the state of America in the 1950s, via Marlowe’s own observations on life and through the dialogue of the other characters in the book. In Chapter 32, Harlan Potter, the millionaire publisher, warns Marlowe that he’s out of his depth on the case and that the media, mass-production and imperfect, modern democracy are things to be wary of. This almost uninterrupted monologue covers more than a page; something that Chandler and his publishers would not have done in previous novels where the action is fast-paced and the dialogue fired off in snappy, clever bursts. Here, though, the detective story is no longer a mere entertainment; it’s also politics, philosophy and a study of the society in which it’s set and, as a result, is richer and more relevant.

The best detective heroes do their noble duty even at a cost to themselves, and at the end of this book Marlowe will grieve for his girlfriend Linda Loring and for Terry Lennox as he allows them to go on their way. Chandler shows us that he knew a thing or two about world literature as well as the human condition when he paraphrases the French novelist-poet Edmond Haraucourt, to shine a flashlight on Marlowe’s moments of pain: “The French have a phrase for it. They have a phrase for everything and they are always right. To say goodbye is to die a little.”

By the time the crime thriller readership of the 1950s had finished this book, they would have better understood feelings of heartache and loss and, like the detective genre itself, would have felt that they too had grown up.

© Tom Marriot, August 2020

If you like crime fiction, Tom Marriot’s short story set in the world of property, Liverpool Bay, can be accessed via Amazon on Kindle and in paperback: