Over the past decade, building systems have become increasingly sophisticated, offering property owners unparalleled opportunities for control, automation, and data access.

As building systems have grown more advanced, they’ve also developed in both variety and complexity. It’s not just an HVAC and plumbing system anymore; there are air quality sensors, physical and IT security controls, water usage monitors, and a plethora of other data points and features that can alternately inform and perplex.

Data is good; and more data is generally better, but only if you can translate that information into actionable processes that enhance the performance of your buildings and the experience of its occupants.

This is where a master services integrator, or MSI, comes into the picture.

If you’ve never heard of an MSI, you’re probably not alone. But a lot of the country’s largest property owners and institutions—from Brookfield Properties and Simon Property Group to Stanford University—are already availing themselves of this technology.

So, to paraphrase Raymond Carver, what are we talking about when we talk about an MSI?

“We’re talking about the systems and the technologies that are responsible for controlling the comfort and the overall human experience in a facility.” That’s according to Brian Turner, CEO of OTI, one of the leading companies in the MSI space.

“That can include systems like heating and air conditioning, lighting controls, energy metering, water monitoring, leak detection—anything that is doing something in the envelope of the building,” Turner continued. “It’s all about making sure that the facility is comfortable, safe, and healthy for the occupants.”

Edi Demaj, Co-Founder of KODE Labs, one of the most prominent software providers in the MSI and building automation space, further elaborated on the concept.

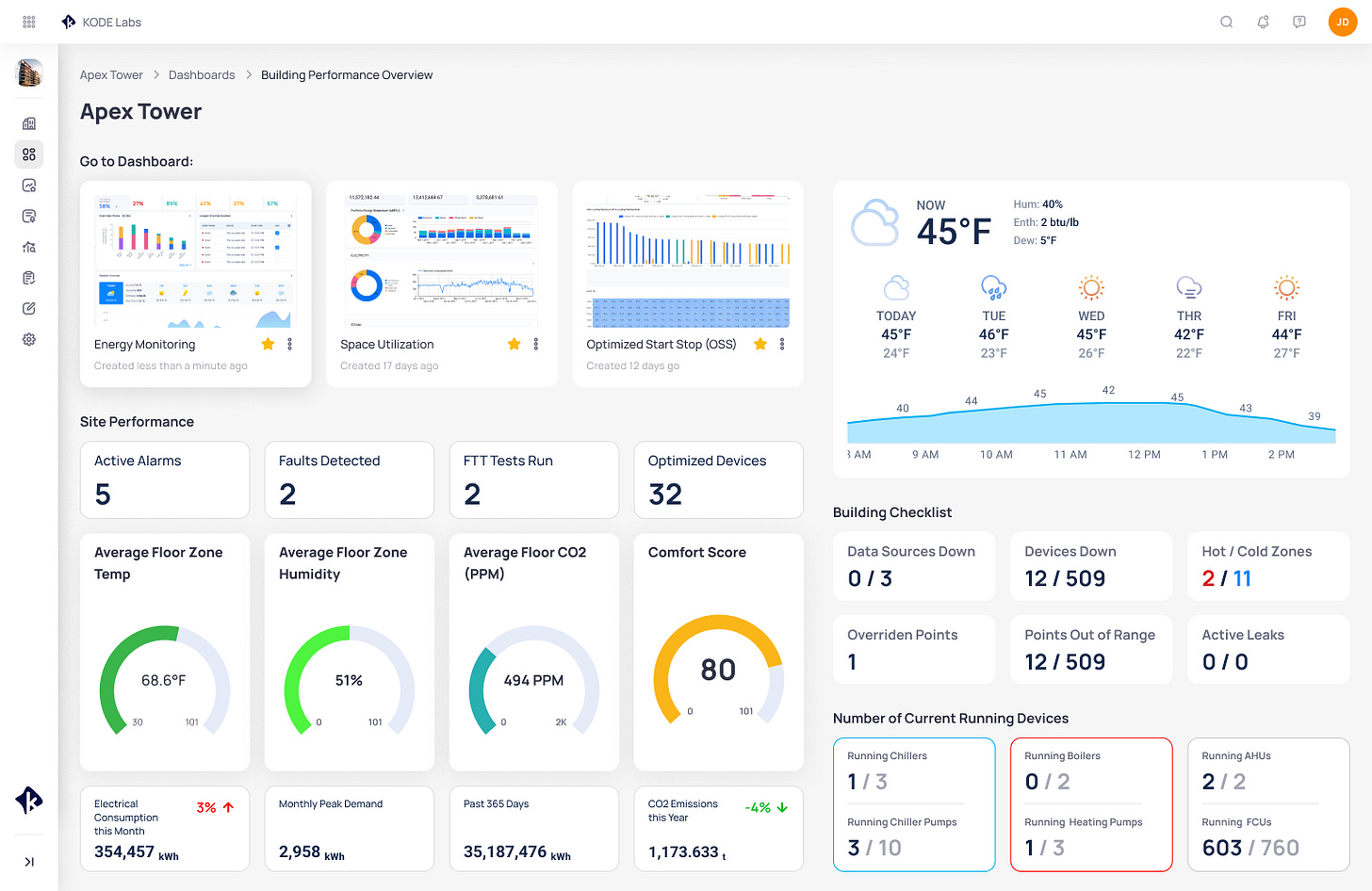

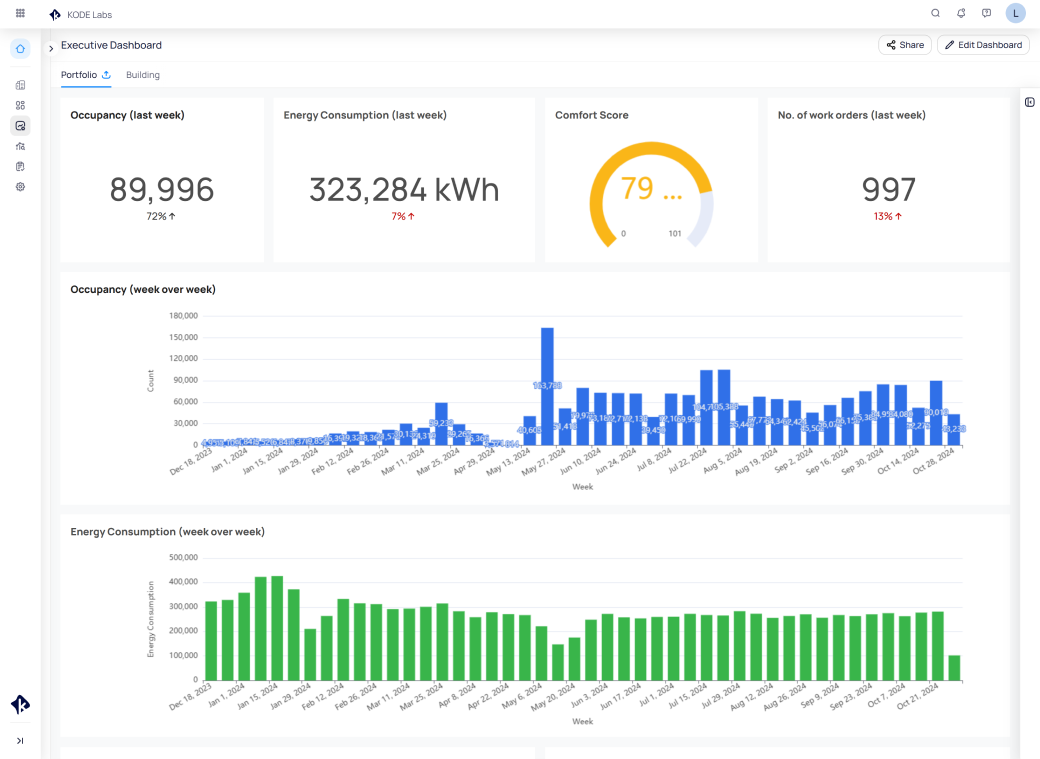

“KODE Labs is a smart building enterprise platform that integrates all core building systems—anything really within the built environment—normalizes it, and then provides the ability to visualize, analyze, command, control, orchestrate, et cetera, all within our platform,” he told me. “So, it serves as that single pane of glass that you can operate your entire portfolio off of.”

Demaj was emphatic about the benefits of these services. “A hundred percent of our client base sees a return on investment off of our platform in less than 12 months,” he said. In other words, Demaj claims that his clients’ entire investment in the platform is recouped within a year, which means that savings after that first year are going directly to the property owner’s bottom line.

And, yet, widespread adoption of MSI software and solutions has been, at least from the perspective of some industry participants, frustratingly slow. But we’ll get to that in a bit.

In today’s letter, we’ll address:

- MSI basics and approaches

- MSI benefits

- MSI adoption and obstacles

- The future of MSIs

MSI Basics and Approaches

One way to think of an MSI that should be familiar to many of the Thesis Driven faithful is that it’s analogous to how a product like Google Home works in your abode. Just as Google Home and comparable applications enable you to control a variety of systems within your domicile—your HVAC, lighting, kitchen appliances, etc.—through a single application, MSI software offers the same functionality for either a single commercial property or portfolio of buildings.

Now, it’s important to note that MSI is a rather broad umbrella term, and it can encompass companies like KODE Labs, which is purely a software provider, as well as entities like OTI, which offers a more robust suite of consulting services.

OTI’s experience in the field is about as long tenured as any company in this nascent industry can claim. They began as Control Co. in 2008 and were reborn as OTI in 2012.

OTI’s approach is to help property owners and asset managers determine the tools they need to monitor and automate their properties. They then, at least in some instances, will help them install and deploy those tools (or oversee another contractor’s work), as well as provide ongoing support in the use and optimization of those systems.

OTI doesn’t make any of the systems it deploys, up to and including the MSI software that brings it all together. However, that hasn’t always been the case.

Turner explained that OTI had developed its own proprietary integration software, known as Buildings IOT. In August of last year, Buildings IOT was sold to Infogrid, which describes itself as a “building intelligence and analytics company leveraging AI and data to curb the impact of the global real estate sector on the planet.”

Turner said that the sale of Buildings IOT enabled his company to take a more agnostic, customer-driven approach to the services it provides.

“When you make your own software, you start to plug people into your software versus choosing the right product for the application,” Turner explained.

Since selling Buildings IOT, Turner said that OTI has developed a stable of six or seven different MSI software solutions, and he likes the flexibility this approach gives him, particularly in terms of cost.

“I have solutions that I can recommend now that we can actually deploy for one-tenth of the cost we could have five years ago,” Turner said.

Unlike OTI, KODE Labs is entirely focused on software. In fact, they’re one of the MSI software solutions that OTI recommends to its clients. “We only do software,” Demaj told me. “We don’t touch anything.”

KODE Labs was founded in 2017. Its name is derived from the two places that Demaj has called home—Kosovo, where he was born, and Detroit, where his family emigrated to when he was a teenager.

The company is headquartered in Detroit and maintains a large office in Kosovo, as well. Growing up in the city, Demaj has witnessed Detroit’s ongoing renaissance firsthand. He also began his career at Bedrock Detroit, one of the city’s largest owners of commercial real estate, and Bedrock was one of the early adopters of KODE’s software.

Unlike Turner, KODE is dedicated to one MSI software—that’s literally their core business. But, similar to OTI, Demaj emphasized that one of his company’s core tenets was an agnostic approach—in KODE’s case to the systems they integrate into their software.

“We’re integrated with over 150 different systems,” Demaj said. “We have the most integrations of any platform in our space and we release new ones essentially every week.”

These systems run the gamut of pretty much everything that goes into a commercial property. “It’s everything from HVAC, lighting, fire, water usage, air quality, EV chargers, work order systems, energy meters, you name it,” Demaj said.

The Benefits of an MSI

The benefits of implementing an MSI in your building or portfolio may seem obvious—it creates efficiencies, reduces expenses, and minimizes environmental impact. However, what I found interesting is how the layers of interconnection between building systems can create somewhat surprising or unexpected benefits.

To illustrate this, Turner offered a simple example. Let’s say it’s the middle of winter, and your air quality sensor detects that indoor air quality in the building is good. If the air quality sensor is aligned with the HVAC system, it can tell the HVAC system to not introduce any additional outside air into the property, which means that the HVAC system doesn’t need to heat more cold air coming into the building. This results in an improvement in HVAC efficiency that reduces wear and tear on the HVAC system, while also minimizing heating expenses and energy usage; it’s a triple win. And that’s just one minor example.

Turner estimated that his clients save 20%-30% in energy usage in year one and an additional 4% per year for several years thereafter until a baseline is reached. He said savings on water are typically smaller, in the single digits percentage wise per year, but that the prevention of a small leak becoming something more catastrophic can yield significant savings.

He also said that gas usage can be reduced notably. For buildings that are switching from gas to electric for heating via heat pumps, “we’re going to help you ride that blip smoother” to reduce electricity costs post-conversion.

Demaj and Turner agreed that it’s when these processes can be introduced at an enterprise level—across a portfolio of buildings—that the savings and efficiencies become particularly compelling.

According to Demaj, because of the automation and efficiency that KODE’s platform enables, Bedrock has been able to reduce its building engineer staff from one engineer per every 125,000 square feet to one engineer per every 250,000 square feet. This not only reduces costs, but also helps companies deal with the industry’s current shortage of skilled labor.

It also makes training new employees simpler and faster. “You don’t have to train them on 15 systems,” Demaj said. “You train them on one platform and you can move them from one building to another seamlessly.”

Some of the improvements from a portfolio perspective can seem almost absurdly simple but can be meaningful in enabling automation and data collection across an enterprise. For instance, Turner talked about how often across a portfolio different names will be used for the same device, depending on who manufactured or installed it. So, if you’re looking at three different properties within a portfolio, a temperature sensor might be “a space sensor in one [property], and a zone sensor in another and just a temp sensor in the third,” Turner said. An MSI will make the naming convention uniform. “And now every temperature sensor has the same identity,” Turner explained. “So, we know that a zone temperature sensor is a zone temperature sensor everywhere.”

Another benefit is tenant control. Because tenants can be given access to these systems within their own space, they no longer need to send requests to a property manager who then has to adjust the temperature or air flow in their space. This, in turn, improves tenant retention.

“If you don’t have the ability to see the entirety of your building—and what I mean by entirety of the building, I mean be able to see all of your systems and the data coming out of those systems and then be able to run all of that data in a way that provides a comfortable, efficient environment for the people that live, work, play in these buildings—you’re going to lose tenants,” Demaj said.

Obstacles and MSI Adopters

I’ve grouped these two concepts together—the entities that have elected to adopt MSIs and the impediments for those who have yet to do so—because, based on my conversation with Demaj and Turner, they seem rather inextricably linked.

As with most things, perhaps the biggest obstacle to the utilization of MSIs in the built environment is, at least from Turner’s perspective, financial. Because not only do MSIs have an initial cost associated with them, but, for many commercial real estate owners, efficiencies in these areas will diminish rather than increase their bottom line.

As most readers are certainly aware, many commercial properties are leased on a triple-net basis, which means that the tenant—not the property owner—is responsible for the electric, gas, and water usage. Even for properties that are leased on a gross basis, owners will often make a tidy profit through common area maintenance charges.

“The CAM charges go back to the tenants, so [property owners] are not incentivized to reduce those costs. Because of their revenue structure, if they did increase their energy efficiency and decrease their consumption and be better citizens on the grid, it would actually [negatively] impact their revenue stream,” Turner said. He added, somewhat ruefully, “If you go to somebody and say, ‘I’m going to decrease a portion of your revenue by 40%,’ they’re going to say, ‘no thanks.’”

Turner said that because of this model, only the highest end Class A office properties utilize his company’s services. In those properties, the tenants are willing to pay a premium—either for the control or reporting possibilities or just the pride (or optics) of being in an ultra-energy efficient property—and that means the owners are amenable to bearing the cost of implementing an MSI.

Alternatively, Turner said that much of his business is driven by large retail centers; Brookfield Properties Retail Group and Simon Properties are among OTI’s largest clients. That’s because for an indoor mall, the comfort of the shopper is truly mission critical.

“The longer the shopper’s comfortable, the longer they’re going to stick around and maybe buy something,” Turner observed.

Turner said that he also does a fair amount of work for prominent private universities, such as Dartmouth College and Stanford University. But, as with office properties, those assignments mostly remained the province of the elite.

“You haven’t heard me talk about Cal State anything. Not to say Cal States aren’t doing something, they’re certainly doing something, but they’re not doing it in as big of a way as some of those private universities,” Turner said.

Turner said he has seen increasing demand from indoor athletic facilities—think the growingly ubiquitous pickleball emporiums—as well as data centers. According to Turner, the latter cohort used to be rather sanguine about how much energy they used; they cared more about uptime. But now “ESG requirements are hitting them.”

Turner bemoaned the fact that multifamily, as an industry, has also been slow to adopt these technologies, at least on a widespread basis. When multifamily owners have availed themselves of OTI’s services, they’ve been mostly focused on the biggest potential impacts to their bottom line, such as water usage sensors to prevent flooding.

Surprisingly, Turner said that there’s not as much demand for new construction as there is for the retrofitting of existing buildings—even though, in some cases, the buildings being retrofitted have been erected quite recently.

He blamed this on the construction industry’s focus on short-term costs, rather than the long-term lifecycle of a building. And because the company constructing a property is often different from the company that will end up owning it, or at least a different division of the same company, Turner said, “It’s like monopoly money with somebody else’s money. It doesn’t make sense. But this is why we end up so often coming in to brand new buildings or relatively new buildings and working for either the new owner or—what’s even more infuriating—the operating team of the same owner that built the building to retrofit systems and put in new stuff that could have been put in during construction for a lot lower cost.”

Unlike Turner, Demaj was more positive about the participation of office owners in the space. He said KODE counts numerous major office owners among its clients; in addition to the aforementioned Bedrock, the company also works with Empire State Realty Trust and Hines Real Estate. Demaj was also less concerned about the barriers that costs present than the obstructions caused by connectivity and the siloing of data.

“The entire world is moving to machine learning and AI,” Demaj said. Meanwhile, the real estate industry is “still figuring out how to access the HVAC in our space. And the reason why is because your top four or five big conglomerates that have run this space for decades and decades now, they’ve had zero incentive to open their systems up.”

Demaj said that when he started KODE, many HVAC companies were resistant to the idea of putting data in the cloud, which constrained the impact an application like KODE could have. Fortunately, Demaj said the situation is evolving, with many companies accepting that if they want to enable automation and machine learning in building systems, data needs to be normalized and available in the cloud.

He also said that most new companies in the space are designing their equipment with APIs (application programming interface), which allows for connectivity between the different systems in a building.

Nonetheless, Demaj was frustrated that not all companies were taking this approach. “Even the new stuff isn’t completely IP open API based, which is complete insanity,” he scoffed.

The Future of MSIs

Given the culture’s infatuation with all things AI-centric, one might expect the future of MSIs to appear stunningly bright, but Turner wasn’t entirely convinced.

“OTI is one of the, I would say, more well-known MSIs in the country,” he told me. “And we responded to maybe a dozen opportunities last year.”

The reason for that relatively sparse demand seemed obvious to Turner. “If you’re going to make an impact in the built environment and how much energy and how much of a drain on the grid the built environment is, you need to go way below the Class A+ buildings. And right now, it’s only the highest of highest end that is affording this.”

He pointed to regulations, like New York City’s Local Law 97, that he believes will stimulate an appetite among property owners for making these kinds of improvements. But he cautioned that government regulations that push companies to make these investments need to be coupled with a regulatory environment that makes it easier for companies to do so.

“In California, we’ve made it so expensive for businesses to invest, and we’ve put so much red tape in the way that it disincentivizes, and we can regulate ourselves into the ground. So, in some ways, I’m definitely supportive of removing or restricting regulation.”

Demaj, in keeping with his general demeanor, was a bit more optimistic. “We’re seeing new companies come into play, and property owners are actually waking up and pushing for their data. They own their data—it’s their buildings—they want to have access to that. So, it’s the entire experience that needed to be revamped, and that is what we are working on and doing for our clients and our partners. And hopefully we’ll see more of that.”

This article was originally published in Thesis Driven and is republished here with permission.