Originally published September 2021.

If I could summarise my most successful investments in one equation it would look something like this:

Cash + Optionality + Astute Capital Allocation = Compounding Machine

Good businesses generate lots of cash. Great businesses generate tonnes of cash, have lots of capital deployment options and, more often than not, choose the right ones. This leads to higher future cash flows which can be reinvested, creating a virtuous circle.

Focus on the cash

Cash flow is the oxygen that gives companies room to invest. It pays the bills and can be used to fund growth projects.

It is not the same as profit, an accounting metric that can easily be manipulated.

Some businesses are very good at generating cash. Others are terrible at it. Most lie somewhere in between. I try to focus my attention on the first category and largely ignore the other two.

Optionality

This part of the equation gets the least attention, but is hugely important.

Plenty of businesses generate cash, but they have little choice of what to do with it.

Let me illustrate with an example.

Just Eat is an online takeaway aggregator. Its website and app connect hungry customers with many independent takeaway outlets.

In the past, Just Eat only partnered with restaurants that had their own delivery networks. That arrangement worked brilliantly for Just Eat because delivering food to peoples’ homes is expensive. Just Eat charged a fee on every transaction via its platform, but got others to do the donkey work. The business threw off cash.

Then something changed. Other takeaway aggregators like Deliveroo and Uber started gaining traction. These privately funded companies didn’t seem to worry about trivial matters like cash and returns. This meant they were happy to arrange delivery on behalf of restaurants. Unsurprisingly, the hungry customer sat at home loved this. Now they could get takeaway from pretty much any local restaurant, regardless of whether they deliver.

Just Eat was in a quandary. Stick to its cash generative business model, but risk losing share, or accept lower economics from expanding into own-delivery? It didn’t have much choice. It had to take on its rivals or risk losing relevance. The result? Declining margins and returns on capital.

Many businesses work like this. You think you have capital allocation options until the competition forces your hand. If I own a restaurant and local competitors suddenly halve their prices, all my plans go out the window. I’m going to have to drop my prices.

This is why competitive moats are so much more important than industry growth. A business largely protected from competition has capital allocation choices others lack, because it operates on the front foot, rather than constantly having to react to whatever the competition are doing (no matter how irrational those actions are).

Nowhere for the cash to go

Just Eat’s market is huge, growing and exciting. All these factors attract rivals. A niche market, particularly an unexciting one that isn’t really growing, is likely to be more insulated from competitive forces.

However, stable niches present another problem. In order to grow, you must either expand the niche or diversify. Both are hard to do. A business selling trombone oil, for example, may generate lots of cash, but there is simply nowhere for it to go.

“Avoid getting into the business of manufacturing trombone oil. You may become the greatest manufacturer of trombone oil in the world, but in the end, the world only consumes a few quarts of trombone oil a year.”

Dan Burke’s advice to Disney CEO, Bob Iger

This is why decentralised conglomerates presided by great capital allocators (like Berkshire Hathaway, Constellation Software, Halma etc) are so powerful. Cash from one business can be diverted to another with better opportunities or used to acquire yet more businesses. The optionality over where to allocate cash is huge. The single business owner who lacks the willingness or ability to buy up other companies is not afforded this luxury.

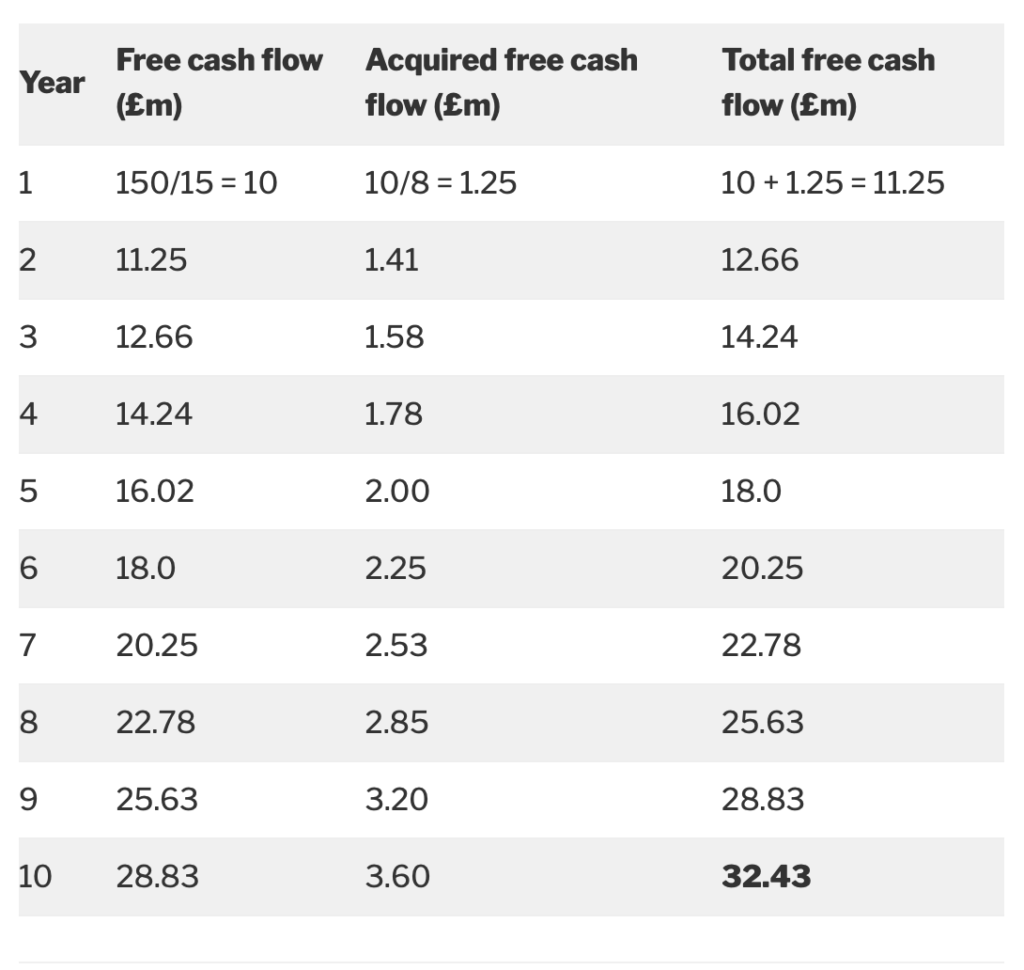

To illustrate how powerful this concept is, consider an example of a publicly traded company valued at £150m. The business trades on 15x free cash flow (FCF), with all annual cash flow used to buy private businesses for 8x FCF (the lower multiple reflecting their small size and illiquid nature). For simplicity, I assume the existing and acquired businesses do not grow.

What are we left with after 10 years?

After a decade, the business is generating £32.4m of free cash flow. Assuming an unchanged FCF multiple, it’s valued at £486m, a compound annual growth rate of 12.5% (remember this assumes no organic growth).

Clearly, having capital allocation options isn’t enough. You need a business manager who allocates that cash smartly. But get these two things right, and layer a cash machine on top, and you’ll have an asset capable of compounding for many years to come.