Working from Home in the USA.

Originally published in May 2023.

“I haven’t been back to the office since COVID,” has become a commonplace response among US employees when asked about their day-to-day work commute. In 2019, 6% of US employees worked from home (WFH) either part or full-time. According to the US Census Bureau Table S0801: Commuting Characteristics, by 2021, due to the COVID shutdown, the percentage of the US workforce that conducted their usual work from home tripled to 18%.

WFH varies greatly across large cities in the US; for example, in 2021, 35% of workers in San Francisco, CA., were working from home, compared to 16% in Houston, TX. There are many factors that drive such divergence.

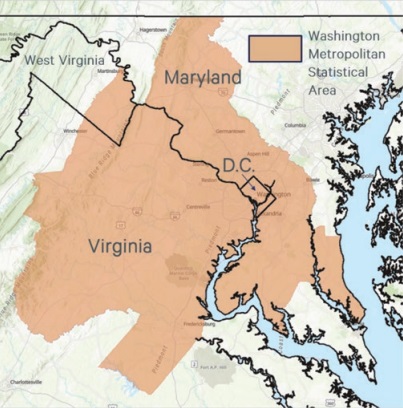

As part of our ongoing research into the future of work, we analyzed WFH in the 50 largest Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) in the United States. Below is an example of the Washington DC MSA. This metro area crosses the boundaries of three states and the District of Columbia, and also includes numerous smaller cities. The land area is 7,000 square miles, about 12 times the size of Greater London. We analyzed at this level — instead of the state or city levels – because a MSA is thought of as one distinct labor market, whereas a state can consist of multiple markets.

Using CBRE’s real estate and demographic databases, we compiled 30 factors that we believe could impact WFH propensity. They included house prices, usage of public transport, demographics (primarily age structure), labor market dynamics, and weather.

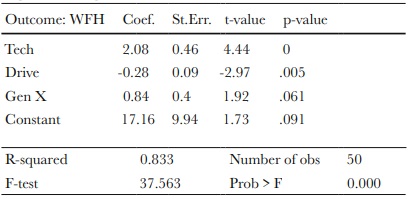

After iterations, taking account the relationships between variables (multi-collinearity) we identified three independent drivers of WFH.

Driver 1: Technology Related Jobs (“Computer and Mathematical Occupations” based on US Bureau of Labor Statistics): a 1% increase in tech jobs will translate to 2% of the workforce working from home. Whilst tech work is more conducive to deconstruction and relocation, the operative factor here is reaction to high living costs in overheated tech clusters. Because of this relationship, recent tech layoffs will have a negative impact on WFH patterns, and booming tech towns will see higher WFH adoption. We further project that as more tech workers leave expensive coastal cities to tertiary markets, we could see WFH pattern to equalize among major cities.

Driver 2: Car Commute: a 1% increase in driving a personal vehicle decreases WFH by 0.3%. We believe the comfort of commuting in a personal vehicle, as opposed to the discomfort of commuting by public transport, encourages more work done in office rather than at home. We think that car based cities will continue to lead on return to the office. Investment in improving the quality of public transport is necessary to restoring the function of cities where use of the office lags.

Driver 3: Gen X: a 1% increase in workers aged 43-58 will increase WFH by 0.8%. We believe several factors are at play: but the most important is that Gen Xers are most likley to have large houses further from the workplace. We project cities with an older workforce will see persistence in WFH patterns.

The economic and demographic variables this study has highlighted suggest that WFH, at heart is an issue of quality of life. Employers that wish to see more workers in the office will have to focus on benefits – free car parking, or car charging, or subsidies for travel by public transport. Cities facing a loss of function in the CBD, should urgently be addressing the speed, quality and cost of public transport.

Our research into WFH will continue. Although workplace trends were pointing to a higher level of WFH prior to the pandemic, the recent changes have been very rapid. They have also taken place in a period of extremely tight labor markets and skill shortages, themselves a product of extreme economic stimulus. Nor is it clear if corporations have viable long term WFH business models. Further evolution should be expected. More globally, it is clear that the United States is something of an outlier, with levels of office utilization trending up only slowly, and currently at about 50% (vis-à-vis 65% in Europe, and closer to 100% in APAC). This suggests the hypothesis that WFH is in part a function of population density. High density Asian cities have smaller houses and shorter commutes. In lower density American cities, the reverse is true. This suggests the further hypothesis that offices in the US will do best in the denser, live work play clusters that exist and are growing in the downtown areas of most America cities, and in the suburbs.