The housing minister describes being stopped in the street by people wanting to thank him for Help to Buy. ‘Several people have stopped me and thanked me for it, because it gives young people access to homes that otherwise they would not obtain,’ Kit Malthouse told the Commons last week. It’s easy to see why, despite mounting criticism of the scheme, it remains a favourite of ministers.

The latest figures show that Help to Buy equity loans have assisted 158,000 first-time buyers onto the property ladder since they were introduced in 2013. Meanwhile there has recently been a modest uptick in owner-occupation. The latest English Housing Survey (EHS) pointed to an increase in mortgaged homeowners from 6.7m to 6.9m (and no change in unmortgaged owners) between 2016/17 and 2017/18. The scale of that shift might be exaggerated by noisiness in the EHS’s sampling but a corner does seem to have been turned, for now.

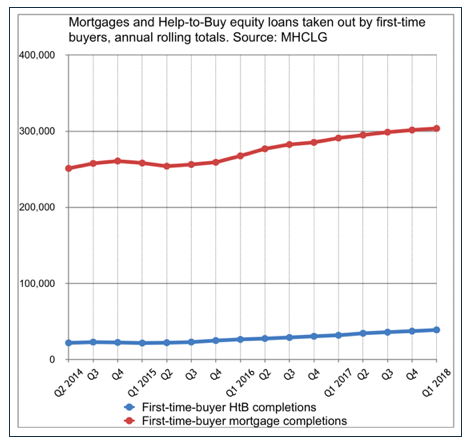

The significance of Help to Buy in that might not be as great as ministers suppose, however. Some commentators have doubted whether this trend is even sustainable without it. But first-time buyer acquisitions in England are now above 300,000 a year (judging by mortgages issued); those using Help to Buy account for about 39,000. The former has increased by about 50,000 since 2015; the latter by about 15,000. Help to Buy has been a factor, certainly – but there are much bigger forces at work.

One of these is that interest rates for those with smaller deposits have been improving. What had been a major obstacle to first-time buyers following the financial crisis – tighter lending criteria and increased costs of borrowing for higher loan-to-value mortgages – have eased somewhat in the past few years. This has given more young people a fighting chance of affording their first property. So too has their reduced stamp duty rates – including a complete exemption on properties under £300,000 – since November 2017.

But just as important has been a decline in small landlord investment in property, due to the tax reforms that George Osborne set in train during his final year as chancellor. This started, in April 2016, with a new three per cent stamp duty surcharge on the purchase of second homes, including buy-to-lets, and the replacement of the ‘wear and tear’ allowance with a less lucrative substitute. Then, from April 2017, higher rate tax relief on mortgage interest costs (for those landlords paying a marginal rate of 40 or 45 per cent) has been – and is still being – withdrawn.

While the stamp duty increase raised entry costs, the withdrawal of mortgage interest relief is chipping away at the margins of many of those already invested. Buy-to-let mortgage completions were down 11.5 per cent in 2018 compared with the previous year, according to UK Finance. The National Landlords Association told a recent conference that net property acquisitions by its members and had been falling since 2016 and were now negative: that is, they are selling more than they are buying and so are withdrawing, as a group, from the market.

This is not quite a stampede and the difference this has made to owner-occupation levels remains marginal compared with the decline that has been witnessed since the early 2000s. But this is a process which is still unfolding and the full impact of Osborne’s tax changes will not be felt until April 2020, by which point higher rate mortgage interest relief will be gone in its entirety.

What is notable too is how relatively few existing landlords have in fact been caught by Osborne’s reforms so far. A Cambridge University study last year found that the withdrawal of mortgage interest relief was the single most cited reason among those selling up, but that most landlords have still incurred no financial loss from it at all. Even by 2020 still 46.5 per cent would be unaffected (because they either do not have a mortgage or their marginal rate is 20 per cent). Little more than a third, 37.5 per cent, would be losing more than £1,000 a year.

There is, then, plenty of scope here for moving this strategy up a notch if ministers want to increase owner-occupation over the next few years. Mortgage rates for first-time buyers do not have much room to fall further, and are in any case in the hands of the banks. What the government could and should focus on, using its fiscal policy levers, is not first-time buyers’ability to pay but landlord-investors’ willingness to pay.

Tax cuts of the kind advocated by the Centre for Policy Studies and the Resolution Foundation – incentivising landlord sales by offering them relief on capital gains tax – are a waste of money and unnecessary when the same effect can be achieved by tax increases. One way to start would be to extend the proposed new one per cent stamp duty surcharge on non-resident buyers to domestic investors too, thus effectively raising the second-home surcharge from three to four per cent. For existing landlords, the withdrawal of mortgage interest relief could be completed in full, so that it is not available at the basic rate either.

To any or all of these measures could be bolted on exemptions for those investing directly into new-build property, such as Build to Rent, thus giving determined investors a route into property but one which genuinely supports and promotes supply efforts – as opposed to the large-scale acquisition of existing properties that has been a hallmark of the expansion of the private rented sector.

If all of this seems tough on the investor, bear in mind that either they own a property or the occupier does. There are valid questions as to whether boosting owner-occupation is desirable or not, but for now at least most people do still want to own their own home and the two main parties are committed to helping them. If that is the goal, it is logically impossible to increase the proportion of housing that is owner-occupied without either reducing the size of the social sector (which in fact very much needs to grow, as a commission set up by Shelter recently detailed) or reducing the size of the private rented sector. Increasing the size of one tenure, relative to the entire housing stock, is always going to involve a trade-off with the size of another: the only real question is how to tilt the scales most efficiently.

This is why ministers should also have the courage to re-regulate the private rented sector. As Dan Wilson Craw set out in a recent Generation Rent paper, there is no reason to expect this would push up rents – and in fact, real rents have been falling since the Osborne tax reforms started coming through – as landlords who exit the market simply sell their properties into owner-occupation. Reintroducing security of tenure, as Labour has now committed to do, would be good for renters but it may also help first-time buyers.

For all of the back-slapping Mr Malthouse is enjoying in the street, Help to Buy equity loans need play little role in this. Other measures may need to be found to support and boost housebuilding output, but if the government is really serious about hitting 300,000 a year then they will anyway. Net supply edged up two per cent last year to 222,190: there is next to no chance of the rest of that difference being made up without a major role for the public sector. The longer ministers put off accepting this fact the less chance they stand of ever hitting their target.

If the goal of Help to Buy really is to help people buy, there are other and better ways. The good news is, the government has already started figuring them out.

Article originally published by Civitas.