With the support of the Atlas Network, CapX is publishing a new series of essays on the theme of Illiberalism in Europe, looking at the different threats to liberal economies and societies across the continent, from populism to protectionism and corruption.

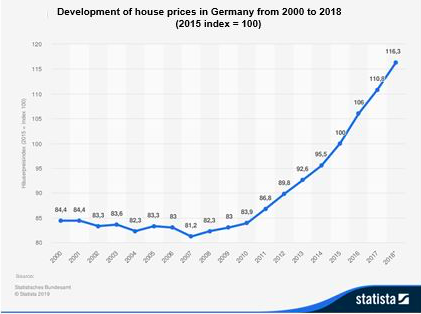

The dramatic rise in house prices is one of the stories of our time. Between 2000 and 2010 low interest rates fuelled house price bubbles around the world. In the U.S, it was this bubble bursting that led to the subprime crisis, which in turn triggered the global financial crash. Only very few developed countries seemed to be immune to spiralling house prices and rents, one of which was Germany, which remained a place of peace and stability with rents and prices barely rising in the years leading up to 2010, in stark contrast to other countries.

Rising rents and house prices

After 2010, the situation changed. The German housing market experienced sharp rises in house prices and rents, especially in major cities such as Berlin, Munich, Frankfurt and Hamburg. These developments were driven by a number of factors. Most importantly, more and more people started moving to German cities. Initially, the newcomers came from other cities and regions across Germany. But as the euro crisis gripped the continent, growing numbers of southern Europeans also arrived in Germany. And finally, starting in 2015, a large influx of immigrants began arriving as a result of Angela Merkel’s policy of open borders. Over a million migrants arrived in Germany in 2015 alone, both war refugees and immigrants who came for economic reasons. In each of the following years, many hundreds of thousands followed in their footsteps.

With such high levels of migration into Germany’s major cities, large numbers of new apartments needed to be developed. Unfortunately, this did not happen. The number of new dwellings built was nowhere near enough to satisfy the sharp rise in demand. The main reasons for this substantial shortfall are Germany’s strict building regulations and slow approval procedures. In Berlin, for example, it currently takes 12 years to draw up a land-use and development plan, which in many cases is a prerequisite for any new construction. In addition, ever tighter environmental regulations have made construction more expensive.

Driven by a lack of supply and rising construction costs, rents and house prices have risen sharply.

The rapid decline in yields in the rental housing sector was also accelerated by the European Central Bank’s zero-interest rate policy. I know the effects of this personally: In 2004, I bought an apartment building in Berlin-Neukölln at a price-to-rent ratio of 6.8. Ten years later, I sold it at a ratio of 24. Today, I would be able to sell the same property at a ratio of over 30.

Rental price brake

Politicians initially reacted to rising rents by introducing what they dubbed the “rental price brake” in 2015. Until then, rent adjustments had only been limited in law for existing tenancies – landlords were not allowed to increase in-place rents by more than 15% over any three-year period. However, when an existing tenant moved out, the landlord was free to negotiate a higher rent with the new tenant. The CDU/CSU and SPD coalition government changed this when they passed a new law in 2015: When re-renting apartments, landlords were only allowed to charge a rent that did not exceed 110% of the “local comparative rent”. The new legislation did allow one major exception: newly constructed apartments. Without this concession, the construction of new housing would have completely stalled. However, the legislation contained a number of ambiguities – for example, the term “local comparative rent” was not defined. There were numerous lawsuits and a host of court rulings. However, rents continued their upward spiral because the underlying causes of the housing shortage had not been eliminated and many landlords did not adhere to the new law anyway.

As with all state intervention, thoughts quickly turned to even stronger regulation. This is a textbook example of the “spiral of intervention” described by the economist Ludwig von Mises 90 years ago: When state intervention fails to achieve the desired results or, as is often the case, actually makes the situation worse, demands for even stricter regulations follow. And this is exactly what has been happening in Germany for some years now. Lawmakers started by tightening the rental price brake and, before the ink was even dry on the newly amended version, calls emerged for even tighter restrictions. This process is aptly described using the example of the Berlin, which has become the focal point of the housing policy debate in Germany.

Why Berlin is rediscovering socialism

First, rent and property price increases have been particularly strong in Berlin, which is largely due to the fact that they started from such an extremely low base compared to other German cities. In 2010, the average rent for an existing apartment in Berlin was an incredibly low €5.21/sqm per month. Even with recent increases, it is still only €6.72 today.

Second, Berlin is governed by a coalition of three leftist parties – the SPD, The Left and the Greens. Senator Katrin Lompscher, who is responsible for construction, is a leading figure in The Left party – the successor to the communist SED, the ruling party in East Germany. She joined the SED in 1981 and one of the first things she did upon becoming Berlin’s Building Senator was to appoint Andrej Holm as Secretary of State, a man who had previously made a name for himself as a great admirer of Hugo Chavéz and Venezuela’s housing policy. Holm was soon forced to resign when stories about his past role with East Germany’s infamous Stasi secret police started to emerge. Nevertheless, he continues to advise the government on housing policy to this day.

Berlin’s Senate has done little to nothing to address the true causes of the city’s housing shortage. On the contrary. The number of development plans has actually halved during Senator Lompscher’s term in office. Investors were vilified as enemies and everything was done to put obstacles in their way. Naturally, the housing crisis got worse and rents and prices continued to rise.

This is when the “spiral of intervention” began. Ever larger swathes of Berlin were designated as “social protection areas” – there are now 57 of them in total. In these areas, property owners’ rights are severely restricted. In fact, they need advance permission from the authorities for almost any and every modification to the property they own. Even the installation of a second wash basin or an extended bathroom can be deemed a “luxury” and forbidden. In addition, the state has increasingly been exercising its right of first refusal and using taxpayers’ money to buy apartment buildings at massively inflated prices. In the past three years alone, 49 apartment buildings have been bought with tax proceeds in order to “remove them from the open market”, as politicians have said.

But that was just the beginning. In 2018, activists launched an initiative to demand the expropriation of all housing companies in Berlin that own more than 3,000 apartments. If successful, more than 200,000 apartments will be effected. The initiative started a petition to call for a referendum – a move that was enthusiastically welcomed by many Berliners – and also attracted support from one of the governing parties, The Left. Kevin Kühnert, the chairman of the SPD youth organisation (the Jusos), has gone as far as to call for a general ban on privately-owned rental apartments. The initiative’s supporters are united by a single conviction: Only state-owned apartments are good apartments. The initiative has openly declared that it wants to “expel” investors from the city.

Parallel to the expropriation initiative, Berlin’s government has announced plans to pass a drastic law that it hopes will put an end to rent increases and could even force landlords to lower rents that are deemed “too high”. The law has not yet come into effect, but the main points have already been set out in a state government resolution.

According to their plans, all rent increases would be prohibited for an initial period of five years. Even in-place tenancy agreements that contain provisions for annual rent increases will no longer apply and landlords will be forced to cut rents. And because the proposed law does nothing to limit the cost to landlords, letting will become less and less economically viable every year. And once the law comes into effect, it is highly unlikely that it will be repealed after the initial five years.

The strategy is clear: Any rental housing that is not formally expropriated will be effectively expropriated. The rights to own and make use of private property are being increasingly eroded. On paper, a property’s owner will still be the owner – but with nothing more than a measly legal title. The power to dispose over the property will increasingly be held by the state.

Lessons from East Germany

The two basic components of Berlin’s new housing policy – a rent freeze and expropriation – are nothing new: they were last seen in socialist East Germany (the GDR). The idea of freezing rents actually has an even longer history in Germany – the country’s first rent freeze was announced on Hitler’s birthday, 20 April 1939, as a gift to the German people. In the socialist GDR, the rent freeze continued – until the country collapsed in 1989. The results were nothing short of catastrophic:

– In 1989, 65% of apartments in East Germany (including 3.2 million built after World War II) were coal heated

– 24% didn’t have their own toilet

– 18% didn’t have their own bathroom

– 40% of multi-family houses in the GDR were severely dilapidated; 11% were completely uninhabitable

A total of 200 historic town centres in eastern Germany were on the brink of collapse. Citizens had to wait many years to be allocated one of the country’s highly coveted prefabricated apartments. By the time the GDR collapsed, so many period apartments in pre-war buildings in Leipzig, Dresden, East Berlin and other East German cities were in such an extremely run-down state that billions of taxpayers’ money needed to be spent on making them habitable again. And it wasn’t only older buildings, but also the GDR’s post-war prefabricated buildings that had to be renovated on a grand scale. What’s more, the large-scale construction of new housing was also necessary to eliminate the housing shortage in eastern Germany. A total of 838,638 apartments were completed in the new federal states and East Berlin in the 1990s with the help of tax incentives – at a cost of €84 billion.

Despite the catastrophic consequences of such policies in the GDR, housing policy in the Federal Republic of Germany is increasingly coming to resemble a planned economy. The lessons of history are being ignored by ideologists. And many citizens, buckling under rising rents without recognising the true causes of their suffering, are coming out in support of these policies. Of course, politicians’ moves towards a planned economy will at best provide fleeting relief to the ailing housing market. In the long run, the problems will only be aggravated. And the predictable response as the problems intensify? Even stronger state regulations and restrictions on the freedom to own and dispose of property. Sadly, housing policy in Germany stands as a classic example of the spiral of intervention described by Ludwig von Mises all those years ago.