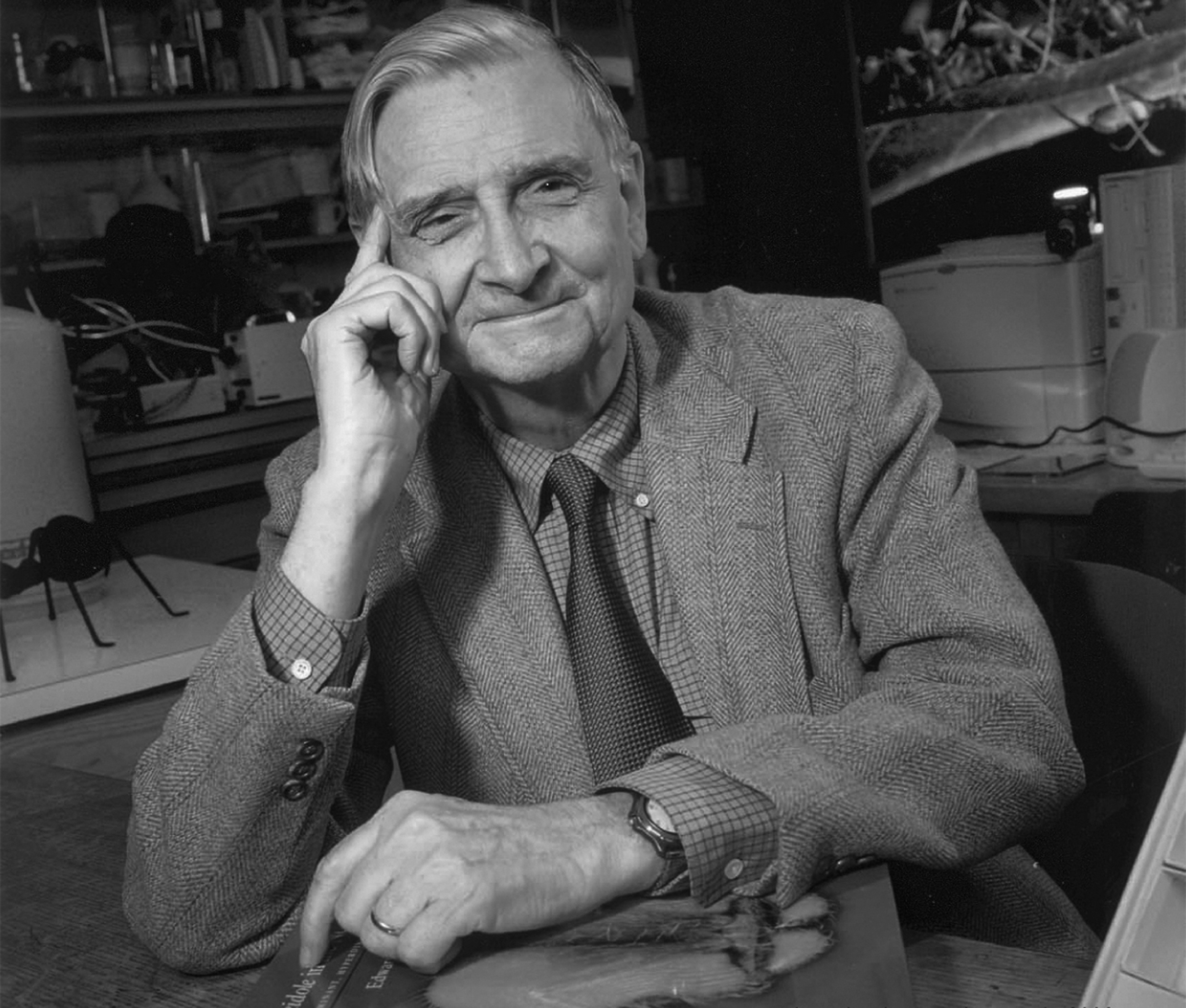

A tribute to the American biologist, naturalist and

writer Edward Osborne Wilson.

Originally published June 2022.

On Boxing Day, 2021, the world lost one of its greatest biologists. Boxing Day was apt, for Edward Osborne Wilson’s passions were communicated with verbal pugilism. Complacency and defeatism were his bug bear and not just as a great entomologist. Known as ‘the ant man’, he theorised that there were 7 tons of ant to every human on earth. He was the champion of biodiversity. Emeritus Professor at Harvard, he twice won the Pulitzer Prize, first for his work ‘On Human Nature’, in 1979, then for his magnus opus, ‘The Ants’ in 1991. His spirit sits like a lively owl in my imagination, full of wisdom, but capable of dealing death to rats.

“I look across the landscape of our own farm and feel his gaze, and the powerful raise of the professorial eyebrow. Much left to do. He inspires still”

One of the causes he embraced was the notion of ‘half earth’, a phrase urging global government to set aside half of the land area of our planet for nature. Only a target of this magnitude, as a minimum, he argued, could deliver the space necessary to curtail the sixth extinction. I look across the landscape of our own farm and feel his gaze, and the powerful raise of the professorial eye brow. Much left to do. He inspires still.

What would he say to DEFRA’s revolution in English agriculture? Farm subsidies are to taper off and end by 2026, and be partially replaced by an offer to farmers called the Environmental Land Management scheme. Split into three, a third of budget will be spent on basic measures (Sustainable Farming Incentive), a third on modular conservation projects (Nature Recovery) and the remainder being the Landscape Recovery scheme, a targeted ‘rewilding’ of around 3% of the countryside. Wilson did not hide his ideas in Ministry speak. An example of his lists is the three great works of evolution: the voice of the nightingale, the hand of man and the heart of the blue whale. Wow.

His forehead would wrinkle and his one good eye would glimmer with hope. He was a great optimist. He would be supportive of the concept of ‘public money for public goods’. He was a great encourager. Many students could attest that he did not like a muddle, nor stomach a lack of drive. His eye would open wider, the wakeful owlish predator. England is “one of the most nature depleted countries on earth”, (according to the World Wide Fund for Nature). Is the historic mess of the Common Agricultural Policy really the best framework from which to assess the cost of nature recovery post EU? And then he would pounce on the 3%. “Not enough,” he would cry. “Where is the ambition?”

He would address the 2022 class of English farmers. “Embrace this future,” he would urge, exhorting innovation and collaboration, and “do not stumble on detail”. His spirit galvanises us for a wade through the treacle of the forthcoming bureaucratic labyrinth.

Were he to ask me, “How will you deal with the changes, young man?” I would answer with excitement. New tree planting grants, for the first time in my career, will enable us to triple the woodland on the farm, enlarging an area of ancient woodland and filling a damp valley with trees. The Landscape recovery, which should apply to our protected marshes, will enable us to expand fen grasslands and build reed beds, buffering extended flooded grasslands so important to our nesting birds. It is hoped that the reorganised funding should make up for the disappearing farm subsidy, as well as cover long-term reduced farm output.

Our farm could be one third ‘nature/land sparing’ and two thirds ‘nature/land sharing’. A conservation gain beyond half earth, realisable, at least on this farm, with determination. I would love to think the great man would invite me into the common room for a celebratory glass of sherry. He might also remind me that I am only one farmer in about 55000 and a lot of work remains to be done!