The covid-19 pandemic has afflicted India with its biggest economic shock since the oil crises of the 1970s. The Indian economy, among the world’s fastest-growing emerging markets four years ago, contracted by a ghastly 24% in Q2 2020 and could even end the year shrinking by 7%, among its worst performances since the Great Depression when my daddy was born in Calcutta and my friend Andy Hoptoun’s great-grandfather Lord Linlithgow was the viceroy for the King Emperor George V.

It is tragic that the pandemic hit India at a time when its financial sector faced a credit malaise, social unrest had erupted in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh and the economic reform momentum had stalled.

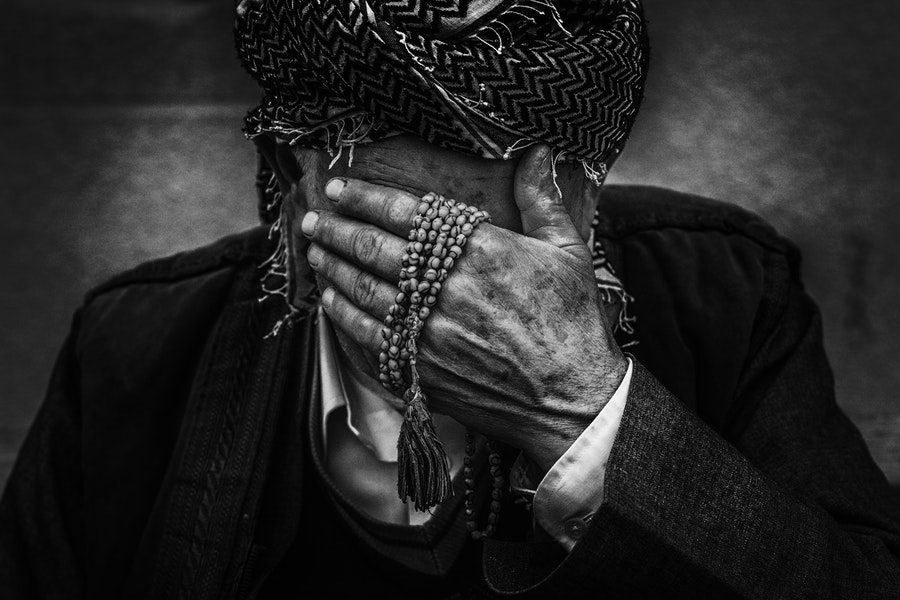

India’s draconian lockdown has amplified social cleavages in a vast, complex society of 1.4 billion people which had managed to raise almost 300 million human beings out of extreme poverty in the preceding decade. This economic fall from grace gives India’s pandemic experience a tragic, even Sophoclean, dimension. India’s lockdown resulted in an estimated 150 million job losses, trauma and megadeath for its untold millions of urban poor and the collapse of several hundred thousand small businesses in an economy unsettled by the NBFC/PSU banking crisis, botched rupee demonetisation programme and the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax.

India’s lockdown resulted in an estimated

150 million job losses and the collapse of several hundred thousand small businesses

India’s covid cases are now 8 million, second only to those of the US. Its fiscal stimulus has not been sufficient to address its tragic public health, social and economic dilemmas. The 24 March lockdown triggered a 45% to 50% collapse in private consumption, investment, construction and manufacturing output.

India’s public finance black hole, gutted by four consecutive years of decelerating GDP, has been exacerbated by the national and state lockdowns. This could lead to a potential sovereign, bank, state and corporate credit risk rating downgrade even as the economy emerges from the lockdown. Any sustainable improvement in discretionary consumption or public finance is hostage to the containment of the coronavirus curve – which has not happened as I write.

Hopefully finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s new $10bn fiscal stimulus scheme will ameliorate India’s socio-economic trauma, though most global economists feel the BJP government’s policy response on the fiscal front is too little and too late. The Reserve Bank of India’s projection that GDP will contract by a staggering 9.5% in the current financial year is itself a de facto indictment of the government’s inadequate policy response.

The ratings agencies will downgrade India’s

debt in any case, since the combined fiscal budget deficit is projected to be a horrific 13%

This is a time for a dramatic fiscal stimulus, not symbolic packages and cosmetic reform. Prime minister Narendra Modi needs to channel the ghost of American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose New Deal was based on his conviction that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself”. A $10bn fiscal stimulus will provide a pathetic 0.4% boost to the Indian GDP, nowhere near sufficient to address the national economic trauma.

The ratings agencies will downgrade India’s debt in any case, since the combined fiscal budget deficit is projected to be a horrific 13% as state tax revenues collapse. While the finance minister’s commitment to fiscal prudence is laudable, India’s immediate sword of Damocles is deflation, not a resurgence in inflation.

India also needs to embrace privatisation of state enterprises – okay, as an ex-Wall Street banker, I know the polite term in Bharat Mata is ‘divestment’. It is too much to hope for a geopolitical rapprochement with Pakistan and an end to the surreal confrontation in Ladakh/Askai Chin with China. South Asia definitely needs a peace dividend and a rupture from the communal demons that have poisoned its history since the fateful August 1947 Partition.

I feel inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s observation: “An eye for an eye only leaves everyone blind.”

The views expressed here are mine and mine alone.