Housing, an essential human need, forms a key sector of the economy. It forms a crucial component of investment and in many countries, makes up a large component of overall wealth. Taking the case of the United States, Zhu (2014) noted that real estate accounts for a third of the total assets held by the non-financial private sector. Besides being a key form of investment, the housing sector also plays a crucial role in the transmission of monetary policy through mortgage markets. Due to the inextricable linkage of the housing sector in the overall economic framework, its booms and busts have significant feedback loops on the wider economy.

Developments in the interwar housing market in the UK serve as a good case study of a housing sector boom supporting economic growth. Some key facts give evidence to this housing expansion. The total number of houses almost doubled from 6.7 million in 1901 to 11.5 million by 1939. Moreover, fixed capital formation in dwellings rose more than 4.5 times from £37 million in 1920 (1.2% of GDP) to £169 million by 1938 (3.4% of GDP)*. What were some of the factors behind this phenomenon? This article analyses the UK housing market during the interwar years and explores the political and economic policies which led to this boom. It also delves into its economy-wide impacts to draw lessons for today where a slow recovery in global housing markets continues.

The UK housing market in the 1930s

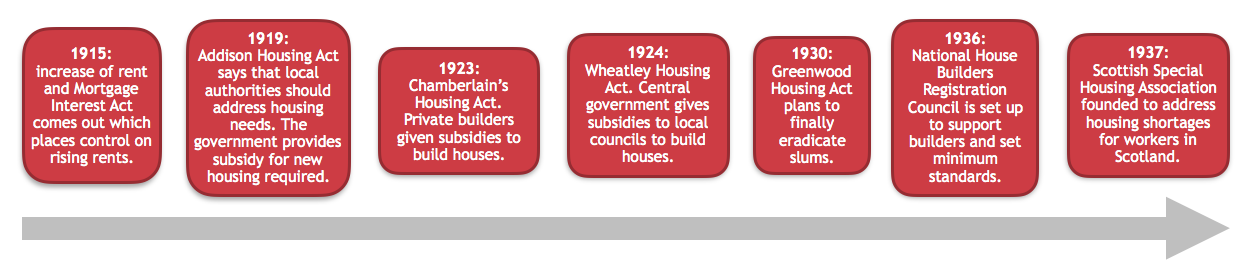

Figure 1: a timeline to show major events in the housing sector

From the end of the First World War, the role of housing in both the social and financial stability of the nation assumed growing political significance. Interestingly, the housing sector used to come under the Ministry of Health from 1919 to 1950. Post the 1918 election, the Prime Minister Lloyd George said that he wanted to create ‘a land for heroes to live in’. This resulted in the ‘homes for heroes’ campaign to provide for better homes for the returning soldiers. A year later, the House and Town Planning Act of 1919 (Addison Housing Act) was the first large scale government project to build housing for social use. The central government provided generous subsidies for housing which resulted in costs being spread out between tenants, the treasury and local councils. The move also encouraged local authorities to engage in large scale housebuilding.

Although the first Labour government of 1924 lasted a mere nine months, they passed a number of key pieces of social legislation including the Wheatley Housing Act. This increased government subsidies for local authorities to build housing for rent for low paid workers. Around 508,000 houses were built under this act. Not only was the purview of providing subsidies focused on local authorities but it was extended to the private sector through the Housing (Additional Powers) Act of 1919 and the Chamberlain Housing Act of 1923. With the above background of UK interwar housing market, it is important to delve into the specific policies which brought about this boom. These are mainly due to the subsidies provided for housebuilding and tax rebates.

Subsidies for housebuilding to private home owners and local authorities

Government incentives to boost the housing sector resulted in an unprecedented building expansion in England and Wales and led to the construction of 1.5 million houses from the end of the World War until 1930 (Becker, 1951). It is estimated that two thirds of these houses received state assistance in their construction which according to Derek H. Aldocroft and Peter Fearon, authors of British Economic Fluctuations 1790-1939, represents 65% of all houses built during that time period. State assistance towards housebuilding was given to local authorities and the private sector.

Public expenditure on housing comprised of capital expenditure on housing by local authorities, subsidy from central government (known as exchequer subsidies) and subsidy from local government (rate fund subsidies). Capital expenditure up to 1928-9 was made ‘out of loans’ but post Great Depression its scope was broadened and could be funded from revenue as well. With the broadening scope of funding for capital expenditure, public expenditure on housing increased from 0.8% of GDP in 1920 (£1.1 billion at 2000 money value) to a peak of 1.5% of GDP by 1938 (£2.2 billion at 2000 money value).

Under the Conservative government the Chamberlain Act was passed in 1923 to encourage the private sector towards housebuilding. This was achieved through the provision of cash subsidies for new buildings, tax relief on mortgage interest and income support for mortgage interest. Subsidies to private owners were terminated from 1929-30 and given to housing associations from 1930-1 onwards. It is estimated that in the period from 1925 to 1930, private owners were paid £22-23 million (0.5% of GDP) for building 362,200 new dwellings, an increase of 4% to the existing housing stock. In an environment of stable employment and greater access to credit more people were enabled to own homes. The private sector also reaped the benefits of this favourable economic climate and contributed towards housebuilding. This can be evidenced from the fact that of the 4.2 million completed dwellings, 31% were built by local authorities, 11% by private developers with state assistance and 58% by unaided private enterprise.

Tax climate

It is important to note that the economic climate of broadly stable prices and modest interest rates during the interwar years could have supported the push the government provided to the housing sector through subsidy provision and tax rebates. Dr Jane Humphries has written that during the 1920s building societies attracted substantial investment due to favourable tax policies creating huge reserves for lending. Beginning from 1927, these building societies encouraged borrowing through gradual liberalisation of mortgage terms thus creating incentives for housing expansion.

Economic impact of housing boom

The consequences of this housing expansion on economic growth were significant. While the proportion of housebuilding to GDP was only 3% in 1932, it constituted 17% of the increase in GDP over the next two years. This is reiterated by economist Dr Arthur Becker who is of the view that it is this boom in housing which can be attributed to Britain’s economic recovery after the slump of 1931. It is important to note that housebuilding was steady between 1931 and 1932 while all other forms of fixed investment were falling, and that it rose by a significant £41 million in 1933*.

Moreover, unemployment exhibited a marked decline in 1933, a year in which there was a significant rise in housing output. Dissecting this increase in employment reveals that employment in building and ancillary trades led employment in all other industries throughout the early recovery. Housebuilding also generated employment in other related industries. Stable employment enabled more people to own homes as more wage earners were able to access credit. This resulted in the proportion of owner occupiers rising to 32% by 1939.

Conclusions

The Great Depression has shown that the housing sector has had a critical role to play towards economic recovery in interwar Britain. Political and economic policies supported the housebuilding boom in an environment of broadly stable prices and interest rates, falling building costs and rise in mortgage financing. Renowned Professor of Economics Dr Nicholas Crafts is of the view that mortgage availability and land planning and usage rules in the UK are markedly different today compared to the 1930s which makes a housing boom propelling the economy difficult to achieve.

Although mortgage financing and land planning rules have changed in the UK, vulnerabilities in the housing sector are damaging for financial stability and the real economy. Although a slow recovery in global housing markets continues today as evidenced by the IMF Global Real House Price Index, the IMF has warned that there must be a concerted effort by policy makers to guard it from becoming another unsustainable boom.

*At 1938 prices